Key points:

- Hydrogen as a fuel offers a carbon-free alternative for hard-to-abate sectors such as heavy road transport, domestic heating, and industries like steel and cement.

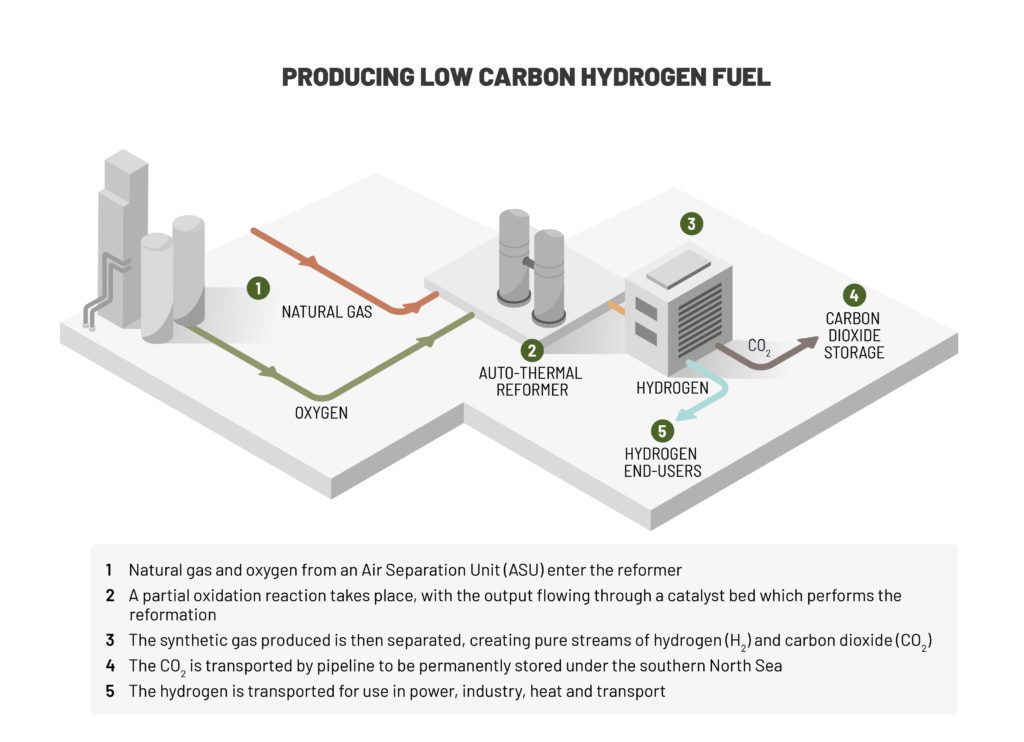

- There are several methods of producing hydrogen, the most common being steam methane reforming, which can be a carbon-intensive process.

- Biomass gasification with CCS is a form of bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) that can produce hydrogen and negative emissions – removing CO2 permanently from the atmosphere.

- The development of both BECCS and hydrogen technologies will determine how intrinsically connected the two are in a net zero future.

Reaching net zero means more than just transitioning to renewable and low carbon electricity generation. The whole UK economy must transform where its energy comes from to low-emissions sources. This includes ‘hard-to-abate’ industries like steel, cement, and heavy goods vehicles (HGVs), as well as areas such as domestic heating.

Reaching net zero means more than just transitioning to renewable and low carbon electricity generation. The whole UK economy must transform where its energy comes from to low-emissions sources. This includes ‘hard-to-abate’ industries like steel, cement, and heavy goods vehicles (HGVs), as well as areas such as domestic heating.

One solution is hydrogen. The ultra-light element can be used as a fuel that when combusted in air produces only heat, water vapour, and nitrous oxide. As hydrogen is a carbon-free fuel, a so-called ‘hydrogen economy’ has the potential to decarbonise hard-to-abate sectors.

While hydrogen is a zero-carbon fuel its production methods can be carbon-intensive. For a hydrogen economy to operate within a net zero UK carbon-neutral means of producing it are needed at scale. And biomass, energy from organic material – with or without carbon capture and storage (in the case of BECCS)– could have a key role to play.

In January 2022, the UK government launched a £5 million Hydrogen BECCS Innovation Programme. It aims to develop technologies that can both produce hydrogen for hard-to-decarbonise sectors and remove CO2 from the atmosphere. The initiative highlights the connected role that biomass and hydrogen can have in supporting a net zero UK.

Producing hydrogen at scale

Hydrogen is the lightest and most abundant element in the universe. However, it rarely exists on its own. It’s more commonly found alongside oxygen in the familiar form of H2O. Because of its tendency to form tight bonds with other elements, pure streams of hydrogen must be manufactured rather than extracted from a well, like oil or natural gas.

As much as 70 million tonnes of hydrogen is produced each year around the world, mainly to make ammonia fertiliser and chemicals such as methanol, or to remove impurities during oil refining. Of that hydrogen, 96% is made from fossil fuels, primarily natural gas, through a process called steam methane reforming, of which hydrogen and CO2 are products. Without the use of carbon capture, utilisation, and storage (CCUS) technologies the CO2 is released into the atmosphere, where it acts as a greenhouse gas and contributes to climate change.

Another method of producing hydrogen is electrolysis. This process uses an electric current to break water down into hydrogen and oxygen molecules. Like charging an electric vehicle, this method is only low carbon if the electricity sources powering it are as well.

For electrolysis to support hydrogen production at scale depends on a net zero electricity grid built around renewable electricity sources such as wind, solar, hydro, and biomass.

However, bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) offers another means of producing carbon-free renewable hydrogen, while also removing emissions from the atmosphere and storing it – permanently.

Producing hydrogen and negative emissions with biomass

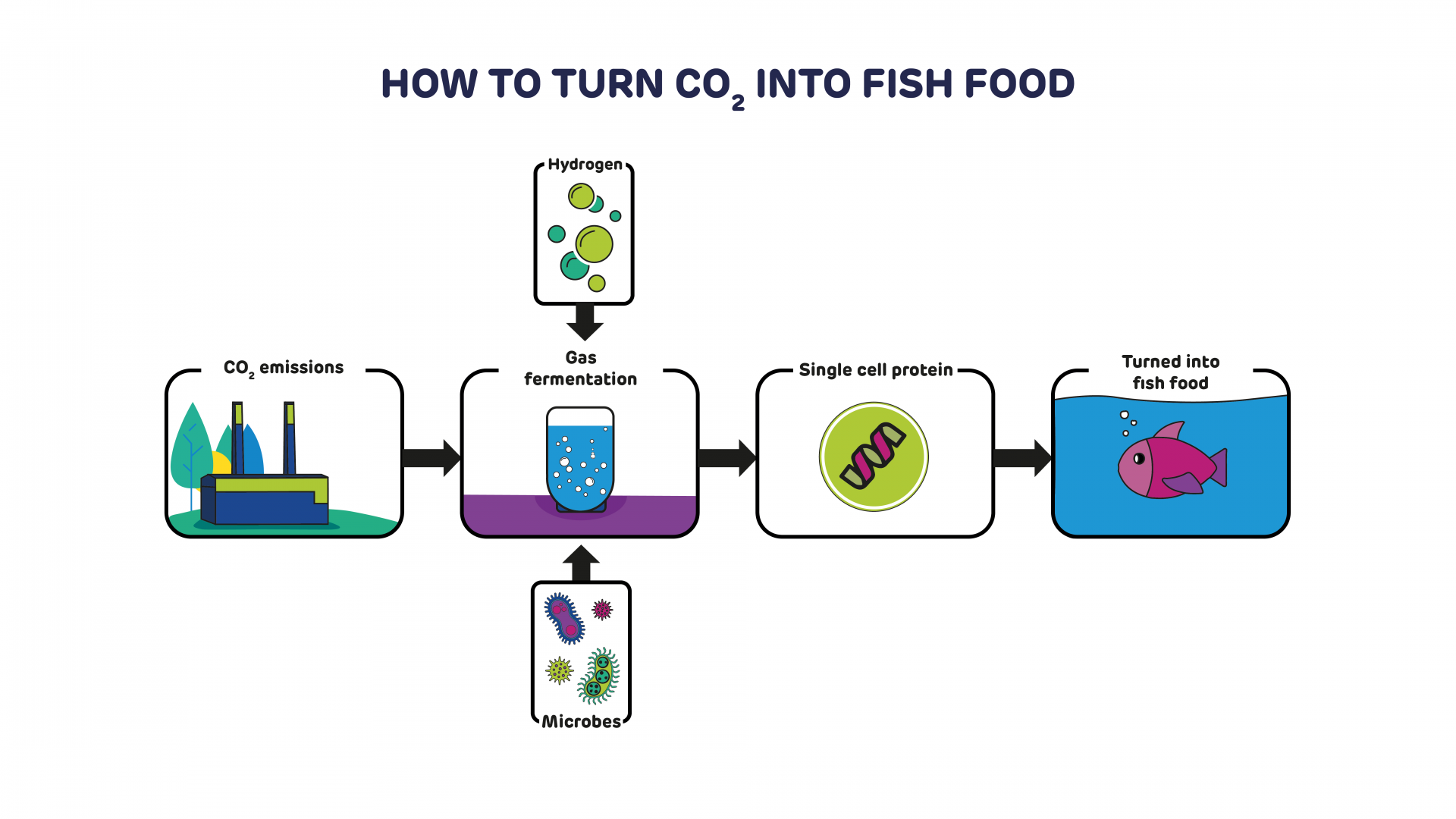

Biomass gasification is the process of subjecting biomass (or any organic matter) to high temperatures but with a limited amount of oxygen added that prevents complete combustion from occurring.

The process breaks the biomass down into a gaseous mixture known as syngas, which can be used as an alternative to methane-based natural gas in heating and electricity generation or used to make fuels. Through a water-gas shift reaction, the syngas can be converted into pure streams of CO2 and hydrogen.

Ordinarily, the hydrogen could be utilised while the CO2 is released. In a BECCS process, however, the CO2 is captured and stored safely and permanently. The result is negative emissions.

Here’s how it works: BECCS starts with biomass from sustainably managed forests. Wood that is not suitable for uses like furniture or construction – or wood chips and residues from these industries – is often considered waste. In some cases, it’s simply burnt to dispose of it. However, this low-grade wood can be used for energy generation as biomass.

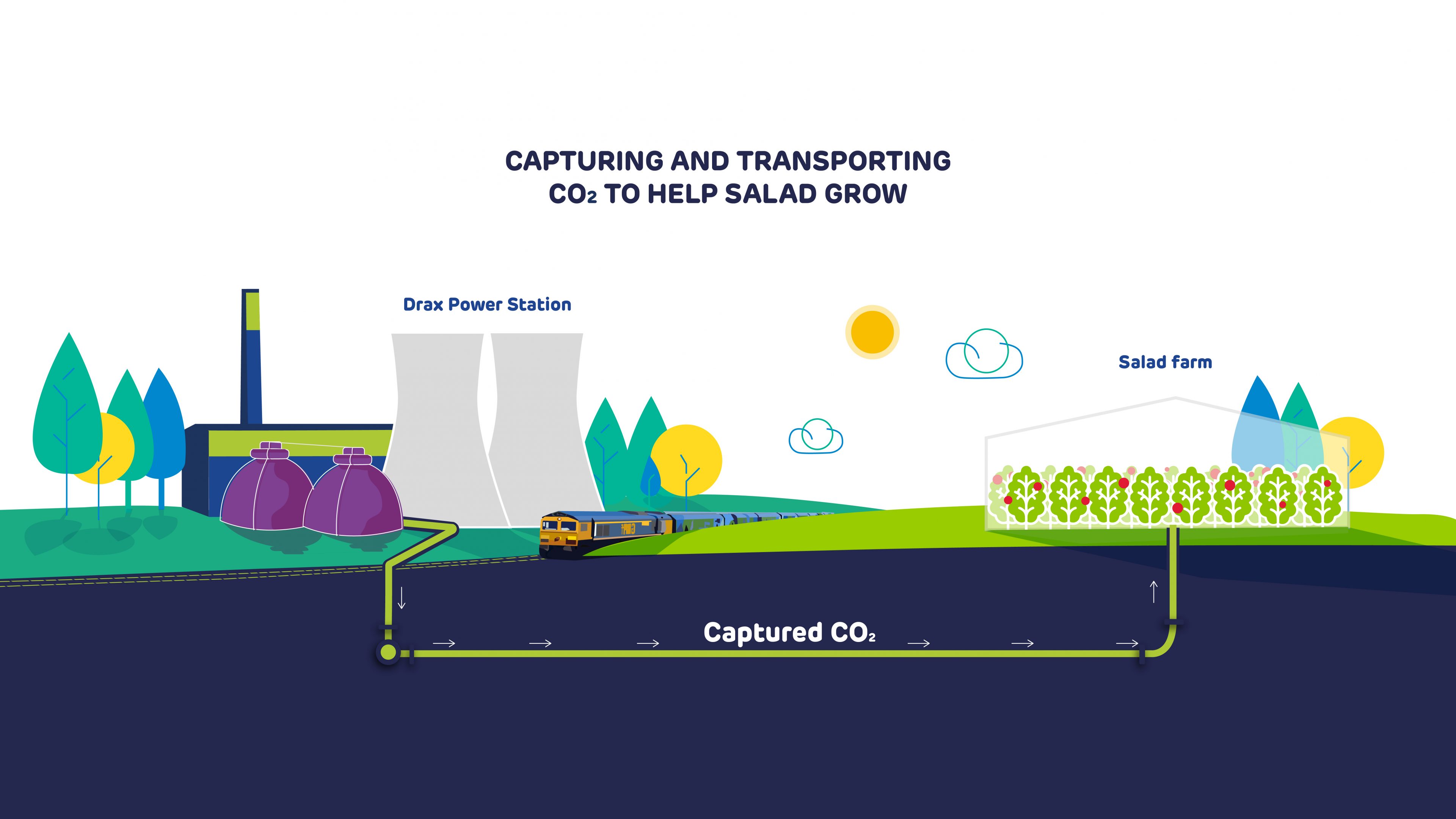

When biomass is used in a process like gasification, the CO2 that was absorbed by trees as they grew and subsequently stored in the wood is released. However, in a BECCS process, the CO2 is captured and transported to locations where it can be stored permanently.

The overall process removes CO2 from the atmosphere while producing hydrogen. Negative emissions technologies like BECCS are considered essential for the UK and the world to reach net zero and tackle climate change.

Building a collaborative net zero economy

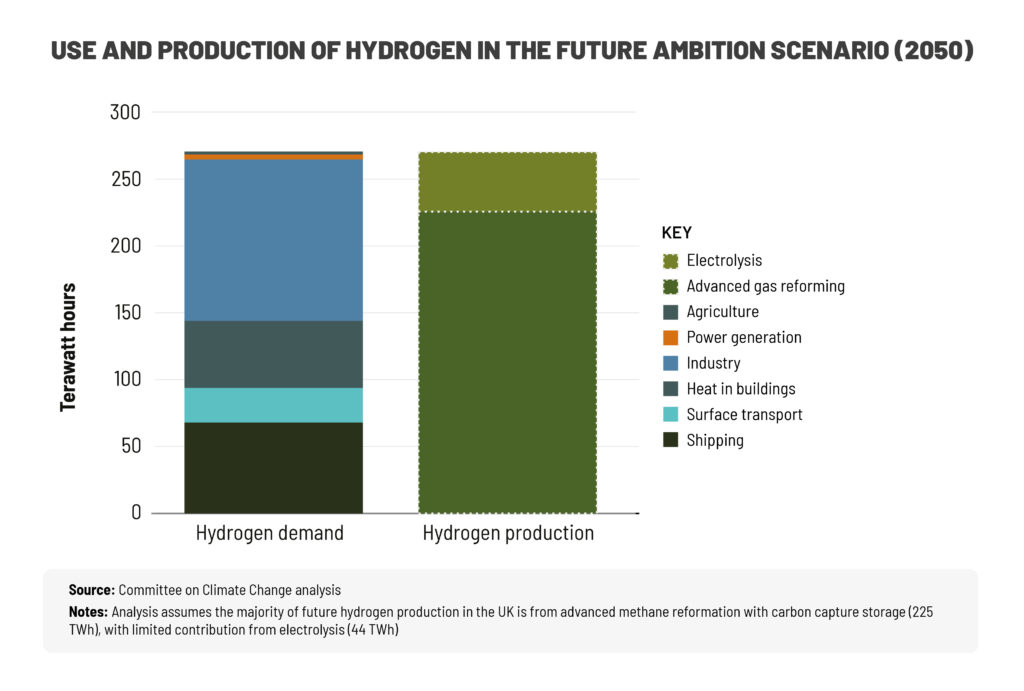

How big a role hydrogen will play in the future is still uncertain. The Climate Change Committee’s (CCC) 2018 report ‘Hydrogen in a low carbon economy’ outlines four scenarios. These range from hydrogen production in 2050 being able to provide less than 100 terawatt hours (TWh) of energy a year to more than 700 TWh.

Similarly, how important biomass is to the production of hydrogen varies across different scenarios. The CCC’s report puts the amount of hydrogen produced in 2050 via BECCS between 50 TWh in some scenarios to almost 300 TWh in others. This range depends on factors such as the technology readiness level of biomass gasification. If it can be proven – technical work Drax is currently undertaking – and at scale, then BECCS can deliver on the high-end forecast of hydrogen production.

The volumes will also depend on the UK’s commitment to BECCS and sustainable biomass. The CCC’s ‘Biomass in a low carbon economy’ report offers a ‘UK BECCS hub’ scenario in which the UK accesses a greater proportion of the global biomass resource than countries with less developed carbon capture and storage systems, as part of a wider international effort to sequester and store CO2. The scenario assumes that the UK builds on its current status and continues to be a global leader in BECCS supply chains, infrastructure, and geological storage capacity. If this can be achieved, biomass and BECCS could be an intrinsic part of a hydrogen economy.

There are still developments being made in hydrogen and BECCS, which will determine how connected each is to the other and to a net zero UK. This includes the feasibility of converting HGVs and other gas systems to hydrogen, as well as the efficiency of carbon capture, transport and storage systems. The cost of producing hydrogen and carrying out BECCS are also yet to be determined.

The right government policies and incentives that encourage investment and protect jobs are needed to progress the dual development of BECCS and hydrogen. Success in both fields can unlock a collaborative net zero economy that delivers a carbon-free fuel source in hydrogen and negative emissions through BECCS.

Chile was an early proponent of energy sharing with its hydrogen programme. The country uses solar electricity generated in the Atacama Desert (which sees 3,000 hours of sunlight a year), to power hydrogen production in a process called electrolysis, which uses electricity to split water into oxygen and hydrogen.

Chile was an early proponent of energy sharing with its hydrogen programme. The country uses solar electricity generated in the Atacama Desert (which sees 3,000 hours of sunlight a year), to power hydrogen production in a process called electrolysis, which uses electricity to split water into oxygen and hydrogen.