This story first appeared in Carbon Capture Magazine.

By Raj Swaminathan, Senior Vice President at Drax.

While there’s little debate that the greenhouse gas emissions that sit at the heart of our planet’s unprecedented warming come from fossil fuel consumption and other human activities, clawing back these carbon outputs is a multi-faceted issue. In addition to efforts to transition to renewable power sources like wind, solar, and biomass, which remain essential to mitigating this crisis, leading scientists agree that reducing emissions is not sufficient; we must go further and faster with carbon removals.

It’s estimated that we’ll need to capture and store as much as 9.5 billion metric tons of CO2 every year by 2050 to reverse legacy emissions enough to achieve international climate targets, according to the IPCC. Today, carbon removal facilities only capture a fraction of the emissions generated across the planet, and we urgently need a spectrum of high-quality solutions to scale our ability to remove carbon from the atmosphere.

At the same time, spiking energy demand – driven largely by the growing needs of data centers, particularly those underpinning artificial intelligence (AI) and blockchain technology, as well as new industrial and manufacturing facilities – also means we need to increase generation capacity rapidly to avoid an energy security crisis. This becomes more difficult to achieve through intermittent sources like wind and solar alone, which can’t be turned up and down when the grid is strained, opening an opportunity for solutions that can provide renewable, baseload power while permanently removing carbon from the atmosphere to fill this vital need.

Bioenergy with CCS – a critical technology for decarbonization

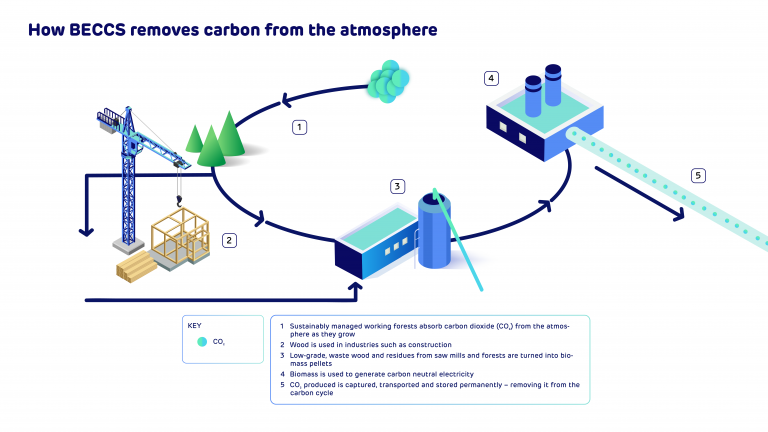

Bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) is a carbon removal technology that uses sustainably sourced biomass to generate renewable energy while permanently sequestering the carbon underground. Because BECCS is one of the only renewable sources that can generate baseload power around the clock, seven days a week, it can serve as the backbone of renewable power grids for when the sun isn’t shining, or the wind isn’t blowing – a role fossil fuels often fill today.

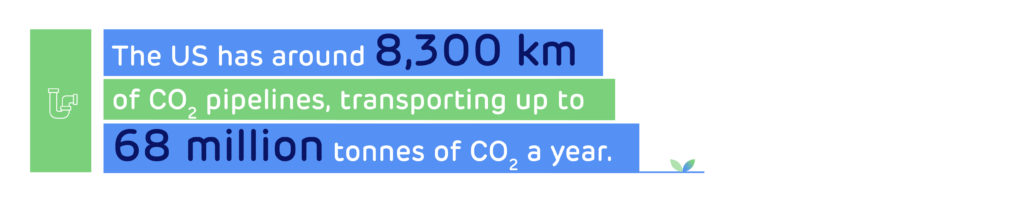

At the same time, BECCS captures post-combustion carbon at the stack and pipelines it into geologic storage, permanently securing it underground. These high-quality carbon removals are more straightforward to measure in comparison with other solutions like nature-based removals, making it much simpler to quantify the overall impact achieved.

Compared to other carbon capture technologies, BECCS also has more diversified revenue streams – including renewable power generation, government incentives for carbon storage, and the sale of carbon dioxide removals (CDR) credits to offset emissions for other companies and industries. Because of this diversification, BECCS not only provides a clearer path to profitability but also offers a high-quality CDR at a much lower price point than alternatives like direct air capture (DAC). This results in a more sustainable and scalable path to adoption.

Due to these advantages, BECCS is positioned to do much of the heavy lifting regarding carbon removals, but it doesn’t replace the need for additional carbon capture and renewable energy solutions. Technologies like DAC, while costlier to operate today, will play an important role in helping to reverse legacy emissions as well; in fact, BECCS could even power DAC facilities to ensure they’re running on renewable energy. The same is true for renewable power technologies – we need far more wind and solar capacity in addition to BECCS.

Pioneering BECCS in the US and UK

Drax believes that BECCS will be integral to decarbonizing the power sector and hard-to-abate industries. To this end, Drax has launched a new independent business unit this year that is focused on becoming the global leader in large-scale carbon removals. This business unit will oversee the development and construction of Drax’s new-build BECCS plants in the US and internationally, and it will work with a coalition of strategic partners to focus on an ambitious goal of removing at least 6 Mt of CO2 per year from the atmosphere.

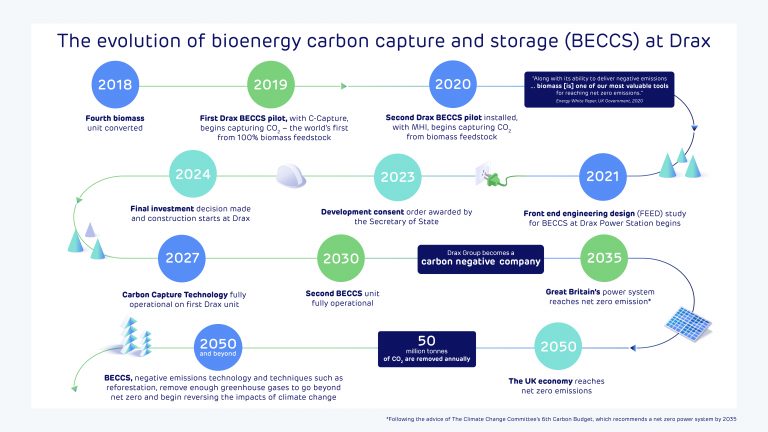

Previously, Drax successfully completed two BECCS pilots at Drax Power Station, the UK’s largest power station that contributes approximately 4 percent of Britain’s generation output and 11 percent of its renewables. The Drax team is now working to outfit Drax Power Station with BECCS technology that will remove an estimated 8 Mtpa of carbon while generating 10 TWh of power. This is slated to be the first carbon-negative power station in the world and is key to achieving Drax’s goal of becoming a carbon-negative company.

Drax is also pursuing an initial target in the U.S. to have two BECCS plants built and operating by the 2030s. These will be the first large-scale, biomass-fueled power stations in North America, generating an estimated total of 4 Twh of power while sequestering approximately 6 Mt of CO2 per year.

BECCS is an essential technology to help achieve global decarbonization targets. While it doesn’t replace the need for additional carbon capture and renewable power generation alternatives, its unique advantages can help reverse carbon pollution from the past while meeting the energy demands of the future.

Scope Two emissions are those which come from the generation of energy an organisation uses. These can include emissions form electricity, steam, heating, and cooling.

Scope Two emissions are those which come from the generation of energy an organisation uses. These can include emissions form electricity, steam, heating, and cooling.