Every summer Great Britain uses less and less coal. This June the fossil fuel’s share of the electricity mix dipped below 1% for the first time ever – for 12 days it dropped all the way to zero.

Spurred on by the beginnings of an uncharacteristically dry, hot summer and a jump in solar generation, the possibility of the country going entirely coal-free for a full summer now looks more achievable than ever in modern times.

This is one of the key findings from Electric Insights, a quarterly report commissioned by Drax and written, independently, by researchers from Imperial College London. It found that across Q2 2018, there were as many coal-free hours as in the whole of 2016 and 2017 combined.

And while the report’s findings are hugely positive, they also hint at where development is still needed. What else does the performance of this quarter tell us about what we can expect in the power sector – in Great Britain and around the world?

Great Britain is slashing coal generation, the rest of the world needs to catch up

Great Britain has reduced its coal-fired power generation by four-fifths over the last five years. Last quarter the country’s coal fleet ran at just 3% of its 12.9 gigawatt (GW) capacity. Coal capacity is now lower than the capacity of solar PV panels (13.1 GW) installed nationwide, with the most recent decline resulting from Drax’s conversion of a fourth unit from coal to biomass.

When coal generation was running, it primarily provided system balancing services overnight in May and June rather than baseload electricity. However, this positive trend is not seen around the world.

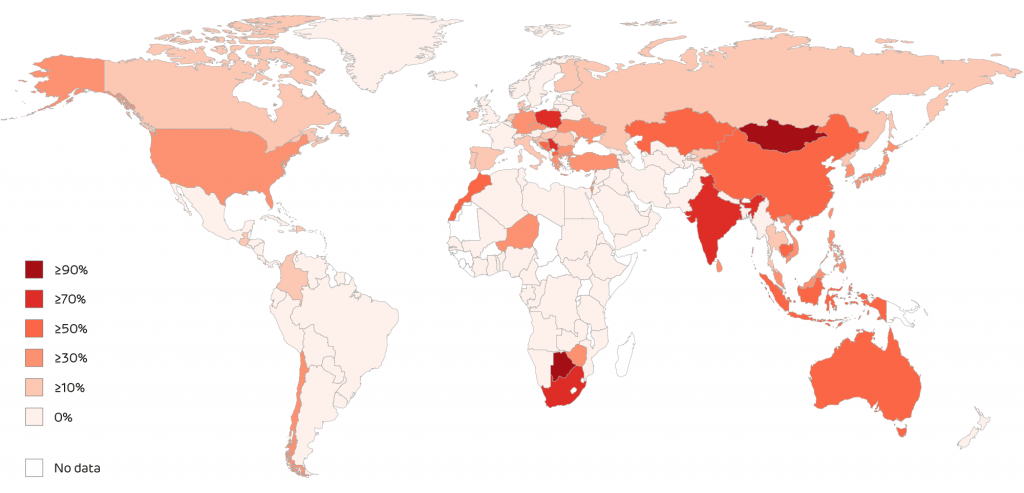

The share of coal in national power systems during 2017

Globally, coal still provides 38% of the world’s electricity – the same amount it did 30 years ago. This comes despite efforts in Europe and North America to move away from coal, and growing investment into renewable generation and technologies.

Overall, Europe’s coal generation dropped from 39% to 22% over the last 30 years, despite some countries – such as Poland and Serbia – still drawing significant generation from the fossil fuel. The US has also reduced its coal generation from 57% to 31% over the past 30 years, as natural gas proves more economical, even in an era of pro-coal policies.

Coal train at rail station in India.

However, in the Middle East and Africa (which draw significant generation from their oil and gas reserves) and South America (where coal accounts for less than 3% of generation), total coal generation is growing. In fact, globally, only seven countries use less coal today than 30 years ago: Germany, Poland, Spain, Ukraine, the US, Great Britain and Canada.

Electric Insights attributes part of this global growth to the continued increase in demand for electricity, particularly in Asia. China, South Korea and Indonesia collectively burn 10 times more coal than they did 30 years ago. India’s coal habit has also increased over the past decade to account for 76% of its electricity generation, while Japan’s usage has grown from 15% to 34% in the same period.

As well as the stresses created by growing demand, this highlights a global disparity in the approach to decarbonising electricity systems, and a need for longer-term, environmentally and socially-conscious market-based initiatives that encourage meaningful movement to lower-carbon electricity sources, such as the UK and Canada’s Powering Past Coal Alliance.

Read the full articles here:

(Lack of) progress in global electricity generation

Britain edges closer to zero coal

Solar farm in South Wales

Decarbonisation is growing, but it’s going to get harder

Great Britain’s decline in coal use has rapidly accelerated its decarbonisation efforts. Annual coal power station emissions have shrunk over the past five years from 129 to 19 million tonnes of CO2 and helped reduce the average carbon intensity of electricity generation to a record low of 195 g/kWh last quarter.

However, this rapid pace of decarbonisation is unlikely to be sustained as growth in renewables faces a plateau, the country’s current nuclear capacity reaches retirement and the target of moving beyond coal by 2025 is completed.

Renewable sources now account for a steady 25% of annual electricity generation. These sources largely came onto the system through policies such as the government’s Renewables Obligation, which is now closed to entrants; Contracts for Differences, the future of which is uncertain for mature technologies like onshore wind and solar; and Feed-in Tariffs for roof-top solar installations which will close in April 2019. The end of these initiative paints a hazy picture of how future renewable capacity will be brought into the system.

Nuclear capacity also looks unlikely to expand at the rate needed to plug gaps in demand, with half of the country’s fleet expected to close for safety reasons by 2025. The Hinkley Point C nuclear power station, meanwhile, is only expected to come online at the end of that year.

Read the full article here:

Has Britain’s power sector decarbonisation stalled?

Ramsgate, Kent during summer 2018 heatwave

Weather will continue to play a major part in renewable generation

If the first quarter of 2018 was defined by low temperatures and heavy snowfall, the second quarter saw the impact of the opposite in weather conditions. From 23 June a heatwave set in around the country that saw temperatures increase by 3.3oC in a week, driving demand to jump 860 MW – the equivalent of an extra 2.5 million households, or an area the size of Scotland.

The increase in demand isn’t as drastic as when cold fronts hit, but if summers continue to get hotter this could change. Today, winter-time demand increases by 750 MW for every degree it drops below 14oC as electric heaters are plugged in to aid largely gas-based central-heating systems. When the mercury rises, however, demand increases by 350 MW for every degree rise over 20oC as businesses turn on air conditioning and the country’s refrigerators work harder.

These heatwave spikes are, at the moment, more easily dealt with than winter storms. While the Beast from the East saw demand reaching a peak of 53.3 GW, June’s topped out at 32.5 GW. The clear skies and long days of June also meant solar PV generation soared, making up for the ‘wind drought’ caused by the high-pressure weather. Wind output floated between 0.3 GW and 4.3 GW in June, far below its quarter peak to 13 GW. However, solar made up for this by peaking past 8 GW for 13 days in June and setting a new record of 9.39 GW at lunchtime on 27 June.

Read the full articles:

How the heat wave affects electricity demand

The summer wind drought and smashing solar

Explore the data in detail by visiting ElectricInsights.co.uk. Read the full report.

Commissioned by Drax, Electric Insights is produced, independently, by a team of academics from Imperial College London, led by Dr Iain Staffell and facilitated by the College’s consultancy company – Imperial Consultants.