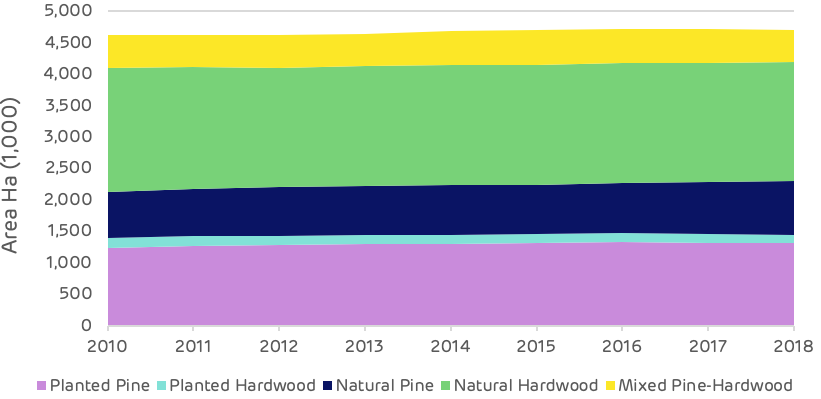

Forest owners have responded to the recovery in pine saw-timber markets, since the global financial crisis of 2008, by planting more forest and investing more in the management of their land. The same period has witnessed increased demand from the biomass sector which has replaced declining need for wood from pulp and paper markets.

The area of timberland (actively managed productive forest) has increase by around 89,000 hectares (ha) since 2010. This change is due to three important factors: new planting on agricultural land; the planting of low-grade self-seeded areas with more productive improved pine; and the re-classification by the US Forest Service (USFS) of some areas of naturally regenerated pine from woodland to timberland.

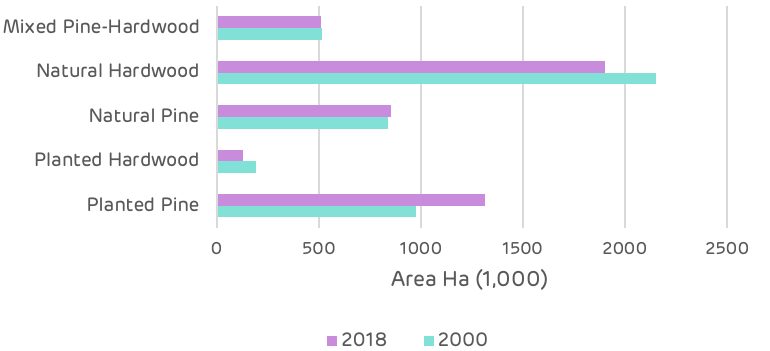

The 2018 data shows that pine forest makes up 46% of the timberland area, of which 61% is planted and the remainder naturally regenerated. Hardwoods cover 43% of the timberland area, with 93% of this naturally regenerated. The remaining area is mixed stands.

Composition of timberland area

Since 2000 there have been some significant changes in the composition of the timberland area with a transition from hardwood to softwood. Pine has increased from 39% of the total area in 2000 to 46% in 2018 and hardwood has decreased from 50% to 43% over the same period.

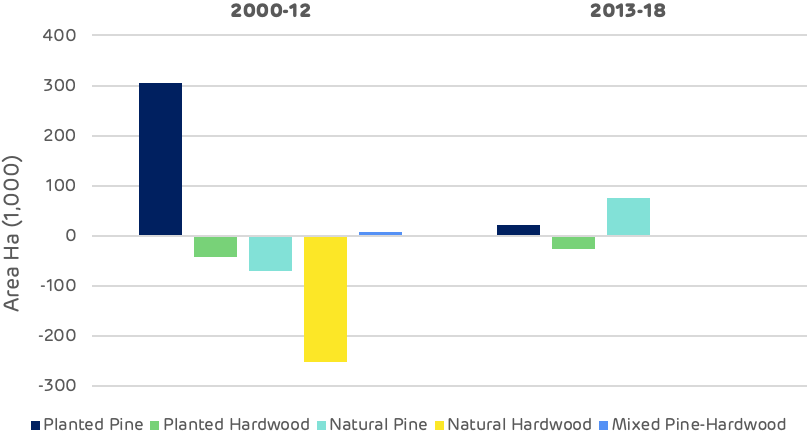

All pine areas have increased since 2000 with naturally regenerated pine increasing by 13,000 ha and planted pine by 340,000 ha since 2000. Mixed stands have declined by 6,500 ha as some of these sites have been replanted with improved pine to increase growth and saw-timber production.

The biggest change has been in the hardwood areas where there has been a decline of around 314,000 ha, despite the total area of timberland increasing by 31,000 ha.

Change in forest type

This change has been driven by private forest owners (representing 91% of the total timberland area), seeking to gain a better return on investment from their forest land.

Hardwood markets have declined since the 2008 recession and demand for hardwood saw-timber has not recovered. Demand for pine saw-timber has rebounded and is now as strong as pre-crisis.

Pine also offers much faster growth rates and higher total volumes in a much shorter time frame (typically 25-35 years compared to 75-80 years for hardwoods).

The decision to change species is similar to a farmer changing their agricultural crops based on market demand and prices for each product. Where forests are managed for revenue generation then it is reasonable to optimise the land and crop for this objective. This can be a significant positive, from a carbon perspective more carbon is sequestered in a shorter time frame and more carbon is stored in long term wood products, if the quantity if saw-timber is increased.

Increased revenue generation also helps to maintain the forest area (rather than conversion to urban development, agriculture or other uses).

A potential negative is the change in habitat from a pure hardwood stand to a pure pine stand, each providing a different ecosystem and supporting a different range of flora and fauna. There is no conclusive evidence that one forest type is better or worse than the other; there is a great deal of variety of each type.

Some hardwood forests are rich in species and biodiversity, others can be unremarkable. The key is not to endanger or risk losing any species or sensitive habitat and to ensure that any conversion only occurs where there is no loss of biodiversity and no negative impact to the ecosystem.

It is not clear whether all of the lost hardwood stands have been directly converted to pine forests, some hardwood stands may have been lost to other land uses (urban and other land has increased by 400,000 ha). Some may have been directly converted to pine by forest owners encouraged by the increase in pine saw-timber demand and prices.

Whatever the primary driver of this change it is clearly not being driven by the biomass sector.

Change in forest type – timing

The chart above demonstrates that the biggest change, loss of hardwood and increase in planted pine, occurred between 2000 and 2012, prior to the operation of the pellet mills. Since 2012, there has been no significant loss of natural hardwood and only a small decline in planted hardwood.