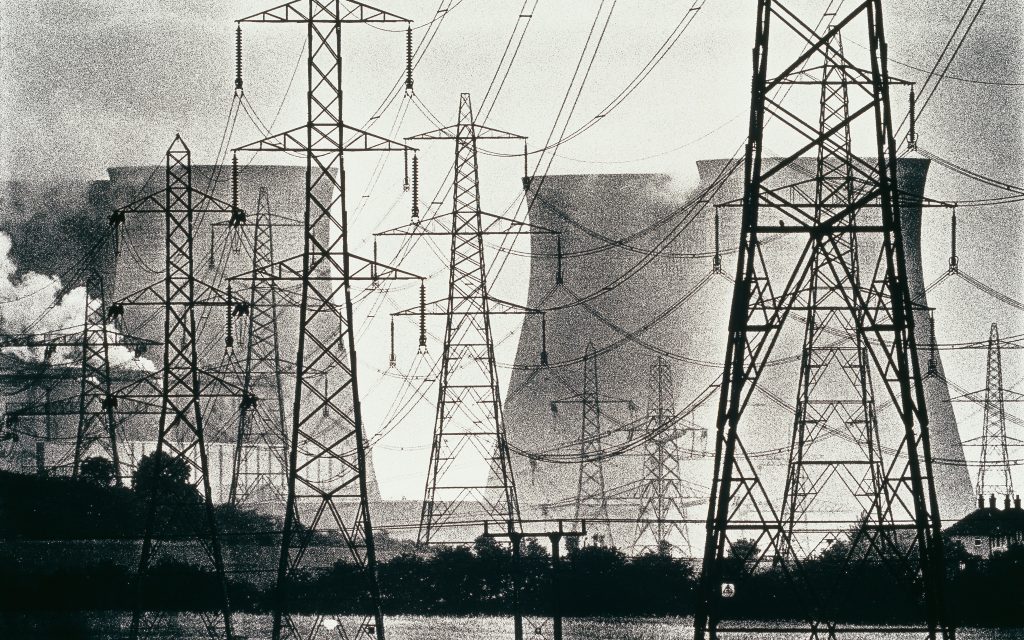

Pylons are one of the most recognisable and perhaps divisive symbols of Great Britain’s electricity system.

There are plenty who decry these metal giants as blotches strung across the country’s green and pleasant landscape. But time has turned the 1930s designs of Great Britain’s pylons into something of a modernist classic, even beloved by some.

What pylons symbolise, however, is more than just the modernisation of the country in the first half of the 20th century. They also represent the promise of safe and reliable electricity for all. There are now more than 90,000 pylons across Great Britain and while the energy system continues to evolve, pylons have changed little since they first went up outside Edinburgh in the 1920s.

Miesbach to Munich

The first successful attempt to transmit electricity over long distances using overhead wires took place in 1882. German engineer Oskar von Miller and his French colleague Marcel Deprez successfully transmitted 2.5 kilowatts of electricity 57km along a telegraph line.

The simple iron line transmitted a 200 volt current from a steam engine-powered generator near Miesbach to the glass palace of Munich, where it was used to power the motor for an artificial waterfall. The line failed a few days later, and even though it may be a world away from today’s 800,000 volt ultra-high voltage transmission lines, this first trial laid the foundation for the way we move energy today.

Egypt to Edinburgh

Jump to 1928 and there was something new arising on Edinburgh’s horizon. The first “grid tower” was erected here on July 14th as part of the recently established Central Electricity Board’s ambitious project to create a “national gridiron”.

Connecting 122 of Great Britain’s most efficient power stations to consumers was a mission that required 4,000 miles of cables, mostly overhead. Sir Reginald Blomfield was called in to tackle this grand challenge.

Blomfield adopted a design submitted by the American firm Milliken Brothers for the “grid towers” that would criss-cross the country. A staunch anti-modernist – as he made clear in Modernismus, his attack on modern architecture – Blomfield looked to ancient Egypt to name his steel towers.

In Egyptology, a pylon is a gateway with two monumental towers either side of it. These represented two hills between which the sun rose and set, with rituals to the sun god Ra often carried out on the structures. It was an epic name to match the grand ambitions of creating a national grid.

By September 1933 the last of the initial 26,000 pylons that made up the National Grid were installed, less than a third of the 90,000 that make up the system today. The grid was now ready to operate, on time and on budget.

Around the world to underground

As the energy system continues to evolve Great Britain’s pylons are changing too. In 2015, the National Grid unveiled a new Danish-designed pylon that shifts away from the classic industrial tower to a T-framed ski-lift style model designed to minimise the visual impact of the pylons on the landscape.

Another approach also being adopted is burying cables underground. The process of digging tracts and burying cables for thousands of miles could cost as much as £500 million but could help preserve areas of natural beauty while ensuring the whole country has access to the safe and reliable electricity it has come to expect.

As with all change, these announcements have caused a surge in nostalgia for the pylon remembered from childhood car journeys across the country.

Around the globe electricity pylons are now ubiquitous and are being pushed to new technological limits. In 1993 Greenland became home to the longest stretch of overhead powerline between pylons in the Ameralik Span, while China’s Zhoushan Island Overhead Powerline Tie set the record for the world’s tallest pylons in 2010 with two 370-meter towers.

Despite the advancements, it’s notable how little these structures have changed from the those first installed around the world. The proposed humanoid sculptures of Icelandic architecture firm Choi+Shine bare a resemblance to the original skeletal towers of the 30s. And it shows just how successful those original pylons have been at delivering much-needed electricity to homes and businesses around the country.