Bitcoin is having a breakout year. Its price fluctuations are making headlines all over the world and major investment banks are finally beginning to take it seriously. In short, bitcoin is no longer a fringe currency – it’s becoming a major player.

But for all the advantages it and other decentralised currencies offer, such as low-transaction fees and no intermediaries, there’s a fundamental problem at their core: they use an extraordinary amount of electricity.

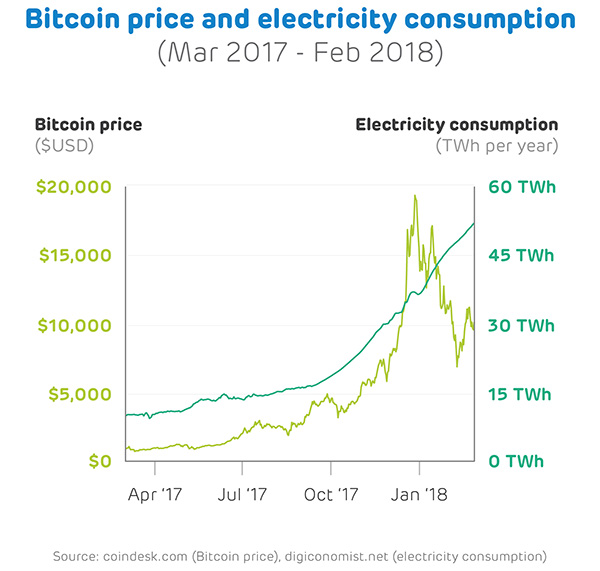

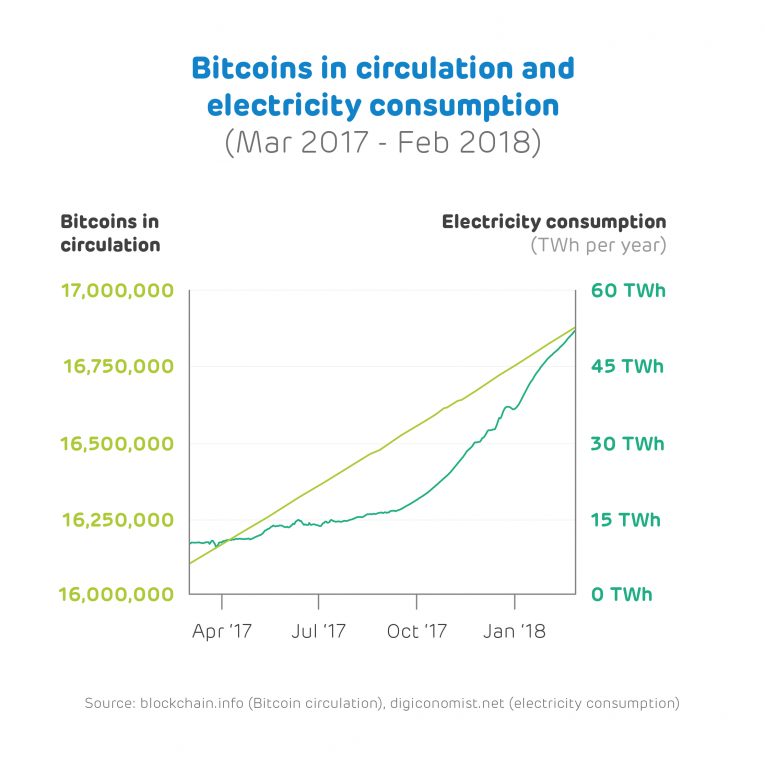

According to bitcoin analysis site Digiconomist, the bitcoin network now uses more than 52 terawatt hours (TWh) every year – more than the whole of Portugal, Ireland or Peru. If this rate of growth continues, it’s forecast that by July 2019 it is expected to use more electricity than the US.

So, while bitcoin may be heralded as a saviour from the monopolies of big banks, what does its incredible appetite for electricity spell for the world’s power networks?

Why does bitcoin use so much electricity?

Bitcoin might be an entirely digital currency, but it still needs to be ‘created’, and this requires a process called bitcoin mining.

Bitcoin is a decentralised network, meaning transactions are carried out directly between parties without any central authority. Instead, bitcoin securely records all its transactions through a network made up of thousands of users’ computers.

Bitcoin mining is essentially the process of recording and adding these transactions to the public network or ledger – known as the blockchain. Every 10 minutes, each pending bitcoin transaction is converted into a complex mathematical problem that needs to be solved.

This is where the ‘mining’ computers come in, which use high-powered processing hardware to tackle the mathematical equations and ‘solve’ each transaction. The first miner to successfully crack one of these problems adds that bitcoin transaction to the ledger and is rewarded with an amount of newly ‘mined’ bitcoins – currently set at 12.5 bitcoins (BTC), worth roughly $140,000.

This is where the ‘mining’ computers come in, which use high-powered processing hardware to tackle the mathematical equations and ‘solve’ each transaction. The first miner to successfully crack one of these problems adds that bitcoin transaction to the ledger and is rewarded with an amount of newly ‘mined’ bitcoins – currently set at 12.5 bitcoins (BTC), worth roughly $140,000.

This process isn’t a quick one and relies on large numbers of high-powered computers to solve the problems. One of the largest bitcoin mining rigs in the world – in Ordos, Inner Mongolia – is made up of eight buildings crammed with 25,000 machines, all cranking through calculations 24 hours a day.

Unsurprisingly, this huge amount of processing power uses a lot of electricity. It also requires a huge amount of space and generates a lot of heat, all of which have sent bitcoin miners around the world in search of cheap electricity, plentiful space and cold weather.

The search for cheap tech power

Iceland and Sweden have become popular destinations for bitcoin mining thanks to its climate (which keeps computer equipment from overheating) and plentiful electricity. In fact, in Iceland, mining is set to reach 840 gigawatt hours (GWh) this year – more than the 700 GWh used by the country’s households.

Iceland’s high level of geothermal and hydroelectric power means these mining operations have a low environmental impact. However, the same can’t be said of the largest bitcoin miner in the world: China.

While it has an abundance of hydropower and an increasing renewable capacity, a large amount of China’s electricity still comes from coal – 72% of its total generation came from the fossil fuel in 2015. This raises concerns around the environmental impact of bitcoin’s increasing electricity needs.

Digiconomist estimates the emissions of just one large-scale, coal-powered bitcoin mining operation (e.g. the operation in Ordos) could fall between 24-40 tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) per hour – roughly the same as flying a full Boeing 747-400 for the same period.

However not everyone is convinced the network is as energy intensive as reports suggest, and part of the challenge is that – despite knowing how many bitcoins are in existence – there’s no precise way of knowing how much mining is going on.

What is known, however, is that even as cryptocurrency prices fluctuate, mining is increasing. In short, bitcoin’s incredible appetite for electricity isn’t going anywhere soon. But could it get cleaner?

Moving towards cleaner mining

Some companies are tackling the problem of making bitcoin more sustainable by bringing it off grid and linking it directly to cleaner sources of power, much like how tech companies are striking deals with local renewable suppliers when locating data centres.

Hydrominer, for example, is placing mining hardware directly into hydropower stations, while HARVEST aims to use dedicated wind turbines to power mining, which takes pressure off national grids and their electricity sources.

However, a more fundamental change could be possible: making the protocol used to create bitcoins less energy-intensive.

Ethereum, arguably the main rival cryptocurrency to bitcoin, this year switched from proof-of-work-based mining to proof-of-stake. This means coin creation is not depended on high-powered computers cranking through calculations, but instead through owners validating their stake in the cryptocurrency and ‘voting’ on block creation.

Another alternative is Chia Network, which harnesses unused hard drive storage space for blockchain verification Chia ‘farmers’ for offering storage space for the network.

Both have significant ground to cover to catch the market leader, however, so the more pressing question remains: What’s next for bitcoin? And what will happen as the number of available bitcoins decreases?

The future of bitcoin

Like gold there are a limited number of bitcoins that can ever be mined – 21 million to be precise. This means the reward for bitcoin mining halves roughly every four years as they become more abundant. The next drop is scheduled for 2020 when the reward will slide to 6.25 BTC.

But this doesn’t mean they’re getting easier to mine. In fact, it is growing increasingly difficult, and this means more computer power and a need for even more electricity, which in turn means higher overheads.

A report from JP Morgan estimates the price of mining a single bitcoin has grown tenfold in the last year to $3,920, a change that could send miners in search of cheaper utilities. More than this, the added stress on grids could lead to a growth in dirtier (and cheaper) fossil fuels which can generate and power mining operations around the clock.

This could mean that as mining becomes more difficult and rewards drop, it will be controlled by fewer, larger-scale operators which can absorb the spiraling costs. Either way, it’s expected they will be forced to reduce their electricity consumption (or at least the cost of it) to remain economical as the rewards they earn cover less of their expenses.

Ultimately, however, if cryptocurrency is set to play a positive role in our future it must become less electricity intensive and work with evolving energy systems to be as sustainable and progressive for the environment as it could be for the global economy.