Electricity generation is often tied to a country’s geography, climate and geology. As an island Great Britain’s long coastline makes off-shore wind a key part of its renewable electricity, while Iceland can rely on its geothermal activity as a source of power and heat.

One of the most geographically-influenced sources of electricity is hydropower. A site needs a great enough volume of water flowing through it and the right kind of terrain to construct a dam to harness it. Even more dependent on the landscape is pumped hydro storage.

Pumped storage works by pumping water from one source up a mountain to a higher reservoir and storing it. When the water is released it rushes down the same shafts it was pumped up, spinning a turbine to generate electricity. The advantage of this is being able to store the potential energy of the water and rapidly deliver electricity to plug any gaps in generation, for example when the wind suddenly dropsor when Great Britain instantly requires a lot more power.

This specific type of electricity generation can only function in a specific type of landscape and the Scottish Highlands offers a location that ticks all the boxes.

The perfect spot for pumped storage

Cruachan Power Station, a pumped hydro facility capable of providing 440 megawatts (MW) of electricity, sits on the banks of Loch Awe in the Highlands, ready to deliver power in just 30 seconds.

“Here there is a minimum distance between the two water sources with a maximum drop,” says Gordon Pirie, Civil Engineer at Cruachan Power Station, “It is an ideal site for pumped storage.”

The challenge in constructing pumped storage is finding a location where two bodies of water are in close proximity but at severely different altitudes.

From the Lochside, the landscape rises at a dramatic angle, to reach 1,126 metres (3,694 feet) above sea level at the summit of Ben Cruachan, the highest peak in the Argyll. The crest of Cruachan Dam sits 400.8 metres (1,315 feet) up the slopes, creating a reservoir in a rocky corrie between ridges. The four 100+ MW turbines, which also act as pumps, lie a kilometre inside the mountain’s rock.

“The horizontal distance and the vertical distance between water sources is what’s called the pipe-to-length ratio,” explains Pirie. “It’s what determines whether or not the site is economically viable for pumped storage.”

The higher water is stored, the more potential energy it holds that can be converted into electricity. However, if the distance between the water sources is too great the amount of electricity consumed pumping water up the mountain becomes too great and too expensive.

The distance between the reservoir and the turbines is also reduced by Cruachan Power Station’s defining feature: the turbine hall cavern one kilometre inside the mountain…

Carving a power station out of rock

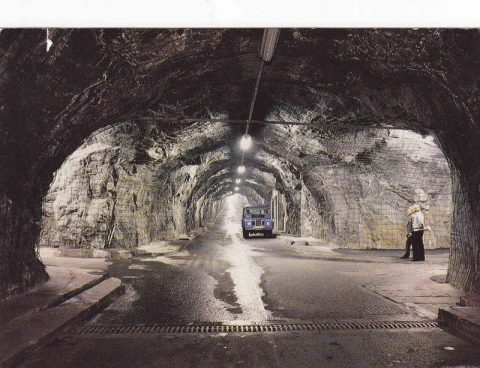

The access tunnel, cavern and the networks of passageways and chambers that make up the power station were all blasted and drilled by a workforce of 1,300 men in the late 1950s to early 1960s, affectionately known as the Tunnel Tigers.

The access tunnel, cavern and the networks of passageways and chambers that make up the power station were all blasted and drilled by a workforce of 1,300 men in the late 1950s to early 1960s, affectionately known as the Tunnel Tigers.

This was dangerous work, however the rock type of the mountainside was another geographic advantage of the region. “It’s the diorite and phyllite rock, essentially granite, so it’s a hard rock, but it’s actually a softer type of granite, and that’s also why Cruachan was chosen as the location,” says Pirie.

The right landscape and geology was essential for establishing a pumped storage station at Cruachan, however, the West Highlands also offer another essential factor for hydropower: an abundance of water.

Turning water to power

The West Highlands are one of the wettest parts of Europe, with some areas seeing average annual rain fall of 3,500 millimetres (compared to 500 millimetres in some of the driest parts of the UK). This abundance of water from rainfall, as well as lochs and rivers also contributes to making Cruachan so well-suited to pumped storage.

The Cruachan reservoir can contain more than 10 million cubic metres of water. Most of this is pumped up from Loch Awe, which at 38.5 square kilometres is the third largest fresh-water loch in Scotland. Loch Awe is so big that if Cruachan reservoir was fully released into the loch it would only increase the water level by 20 centimetres.

However, the reservoir also makes use of the aqueduct system made up of 19 kilometres of tunnels and pipes that covers 23 square kilometres of the surrounding landscape, diverting rainwater and streams into the reservoir. Calculating quite how much of the reservoir’s water comes from the surrounding area is difficult but estimates put it at around a quarter.

However, the reservoir also makes use of the aqueduct system made up of 19 kilometres of tunnels and pipes that covers 23 square kilometres of the surrounding landscape, diverting rainwater and streams into the reservoir. Calculating quite how much of the reservoir’s water comes from the surrounding area is difficult but estimates put it at around a quarter.

“There are 75 concrete intakes dotted around the hills to gather water and carry it through the aqueducts to the reservoir,” says Pirie. “The smallest intake is about the size of a street drain in the corner of a field and the largest one is about the size of a three-bedroom house.”

Pumped storage stations offer the electricity system a source of extra power quickly but it takes the right combination of geographical features to make it work. Ben Cruachan just so happens to be one of the spots where the landscape makes it possible.