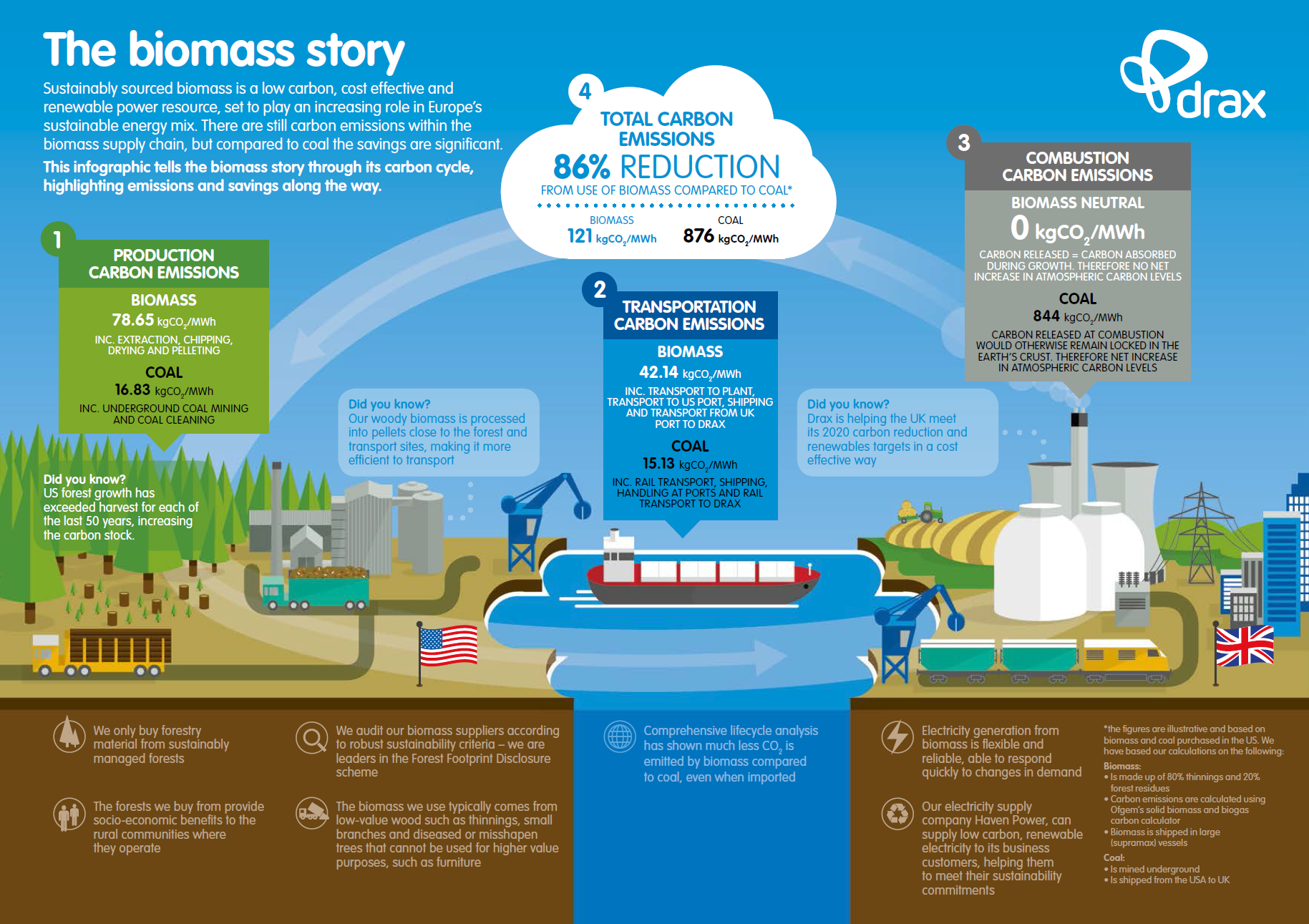

There is an important difference between carbon dioxide (CO2) emitted from coal (and other fossil fuels) and CO2 emitted from renewable sources. Both do emit CO2 when burnt, but in climate change terms the impact of that CO2 is very different.

To understand this difference, it helps to think small and scale up. It helps to think of your own back garden.

One tree, every year for 30 years

Imagine you are lucky enough to have a garden with space for 30 trees. Three decades ago you decided to plant one tree per year, every year. In this example, each tree grows to maturity over thirty years so today you find yourself with a thriving copse with 30 trees at different stages of growth, ranging from one year to 30 years old.

At 30 years of age, the oldest has now reached maturity and you cut it down – in the spring, of course, before the sap rises – and leave the logs to dry over the summer. You plant a new seedling in its place. Through the summer and autumn the 29 established trees and the new seedling you planted continue to grow, absorbing carbon from the atmosphere to do so.

Winter comes and when it turns cold and dark you burn the seasoned wood to keep warm. Burning it will indeed emit carbon to the atmosphere. However, by end of the winter, the other 29 trees, plus the sapling you planted, will be at exactly the same stage of growth as the previous spring; contain the same amount of wood and hence the same amount of carbon.

As long as you fell and replant one tree every year on a 30-year cycle the atmosphere will see no extra CO2 and you’ll have used the energy captured by their growth to warm your home. Harvesting only what is grown is the essence of sustainable forest management.

If you didn’t have your seasoned, self-supplied wood to burn you might have been forced to burn coal or use more gas to heat your home. Over the course of the same winter these fuels would have emitted carbon to the atmosphere which endlessly accumulates – causing climate change.

Not only does your tree husbandry provide you with an endlessly renewable supply of fuel but you also might enjoy other benefits such as the shelter your trees provide and the diversity of wildlife they attract.

No added carbon

This is a simplified example, but the principles hold true whether your forest contains 30 trees or 300 million – the important point is that with these renewable carbon emissions, provided you take out less wood than is growing and you at least replace the trees you take out, you do not add new carbon to the atmosphere. That is not true with fossil fuels.

It is true that you could have chosen not to have trees. You could instead build a wind turbine or install solar panels on your land. That would be a perfectly reasonable choice but you’ll still need to use the coal at night when the sun doesn’t shine or when the wind isn’t blowing. Worst of all you don’t get all the other benefits of a thriving forest – its seasonal beauty and the habitat that’s maintained for wildlife.

Of course, the wood Drax needs doesn’t grow in our ‘garden’. We bring it many miles from areas where there are large sustainably managed forests and we carefully account for the carbon emissions in the harvesting, processing and transporting the fuel to Drax. That’s why we ‘only’ achieve more than 80% carbon savings compared to coal.