Electricity networks around the world differ many ways, from the frequency they run at to the fuels they’re powered by, to the infrastructure they run on. But they all share at least one core component: circuits.

A circuit allows an electrical current to flow from one point to another, moving it around the grid to seamlessly power street lights, domestic devices and heavy industry. Without them electricity would have nowhere to flow and no means of reaching the things it needs to power.

But electricity can be volatile, and when something goes wrong it’s often on circuits that problems first manifest. That’s where circuit breakers come in. These devices can jump into action and break a circuit, cutting off electricity flow to the faulty circuit and preventing catastrophe in homes and at grid scale. “All this must be done in milliseconds,” says Drax Electrical Engineer Jamie Beardsall.

But to fully understand exactly how circuit breakers save the day, it’s important to understand how and why circuits works.

Circuits within circuits

Circuits work thanks to the natural properties of electricity, which always wants to flow from a high voltage to a lower one. In the case of a battery or mains plug this means there are always two sides: a negative side with a voltage of zero and a positive side with a higher voltage.

In a simple circuit electricity flows in a current along a conductive path from the positive side, where there is a voltage, to the negative side, where there is a lower or no voltage. The amount of current flowing depends on both the voltage applied, and the size of the load within the circuit.

We’re able to make use of this flow of electricity by adding electrical devices – for example a lightbulb – to the circuit. When the electricity moves through the circuit it also passes through the device, in turn powering it.

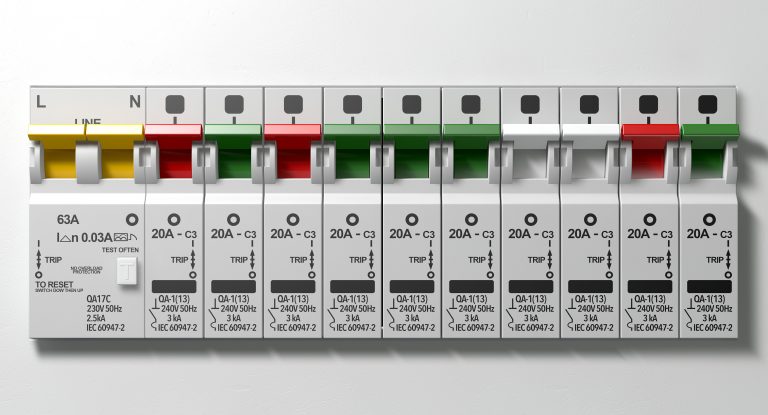

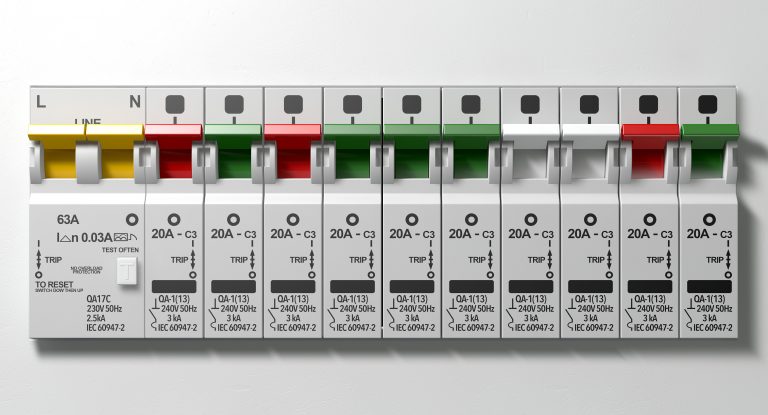

A row of switched on household electrical circuit breakers on a wall panel

The national grid, your regional power distributor, our homes, businesses and more are all composed of multiple circuits that enable the flow of electricity. This means that if one circuit fails (for example if a tree branch falls on a transmission cable), only that circuit is affected, rather than the entire nation’s electricity connection. At a smaller scale, if one light bulb in a house blows it will only affect that circuit, not the entire building.

And while the cause of failures on circuits may vary from fallen tree branches, to serious wiring faults to too many high-voltage appliances plugged into a single circuit, causing currents to shoot up and overload circuits, the solution to preventing them is almost always the same.

Fuses and circuit breakers

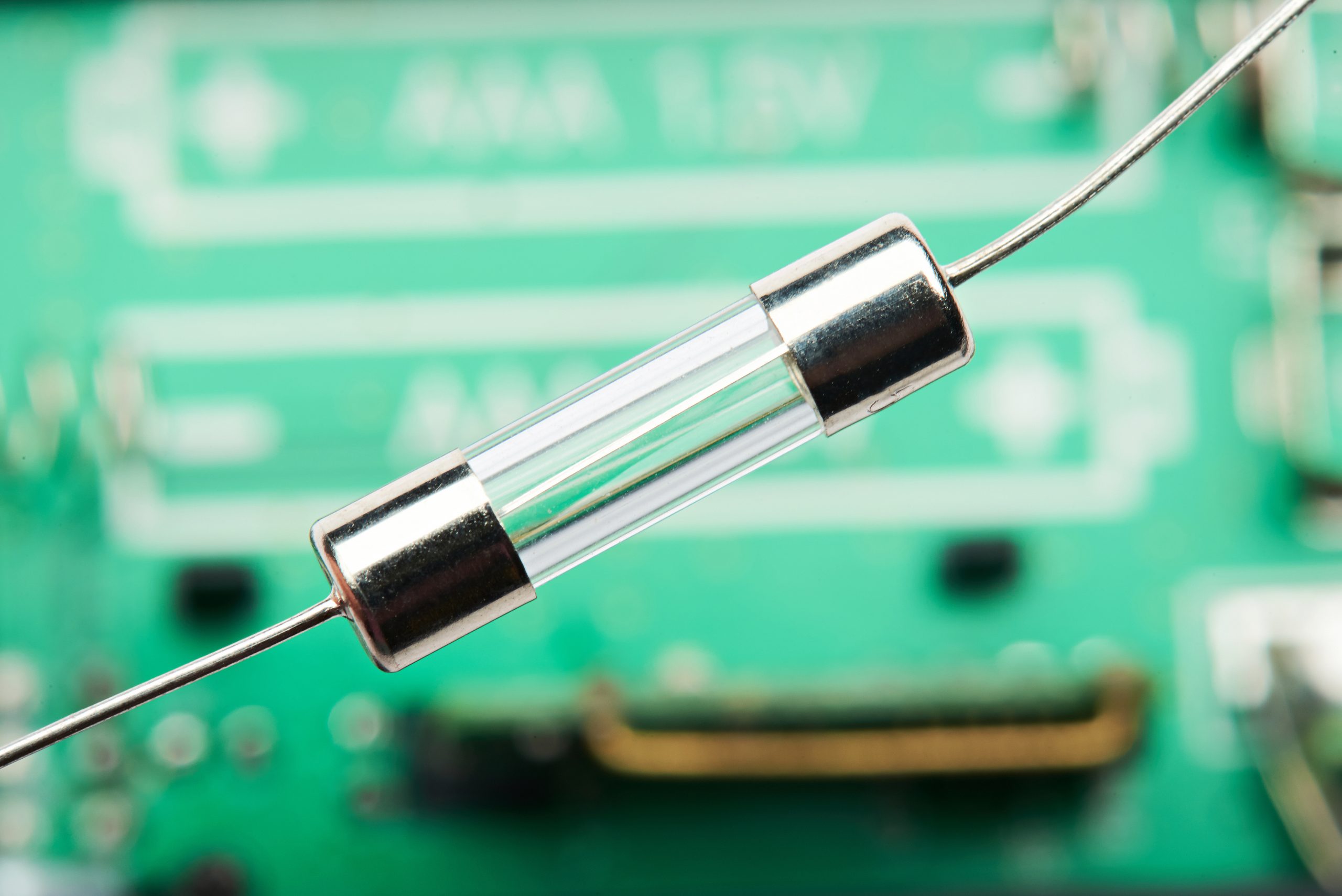

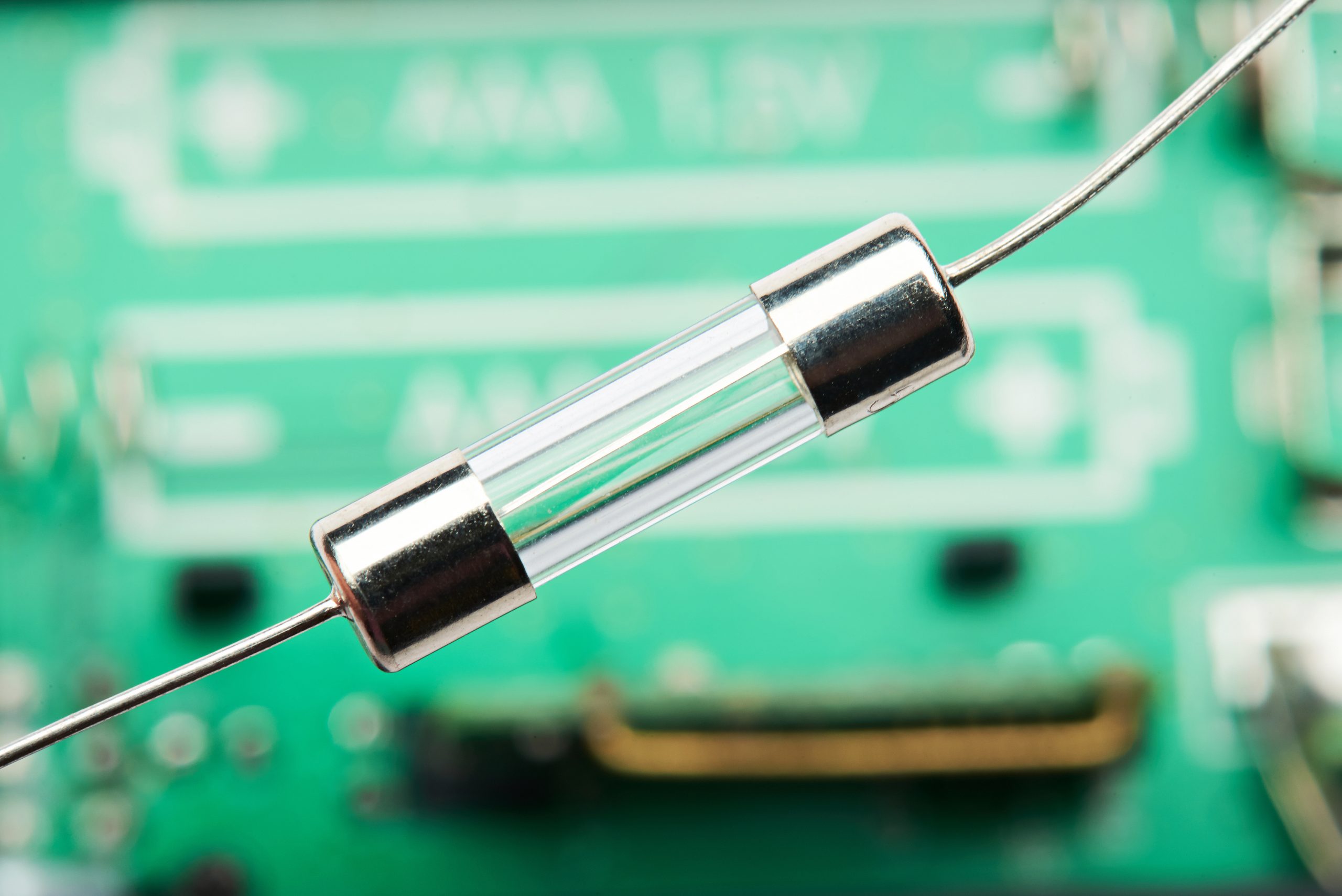

In homes, circuits are often protected from dangerously high currents by fuses, which in Great Britain are normally found in standard three-pin plugs and fuse boxes. In a three pin plug each fuse contains a small wire – or element.

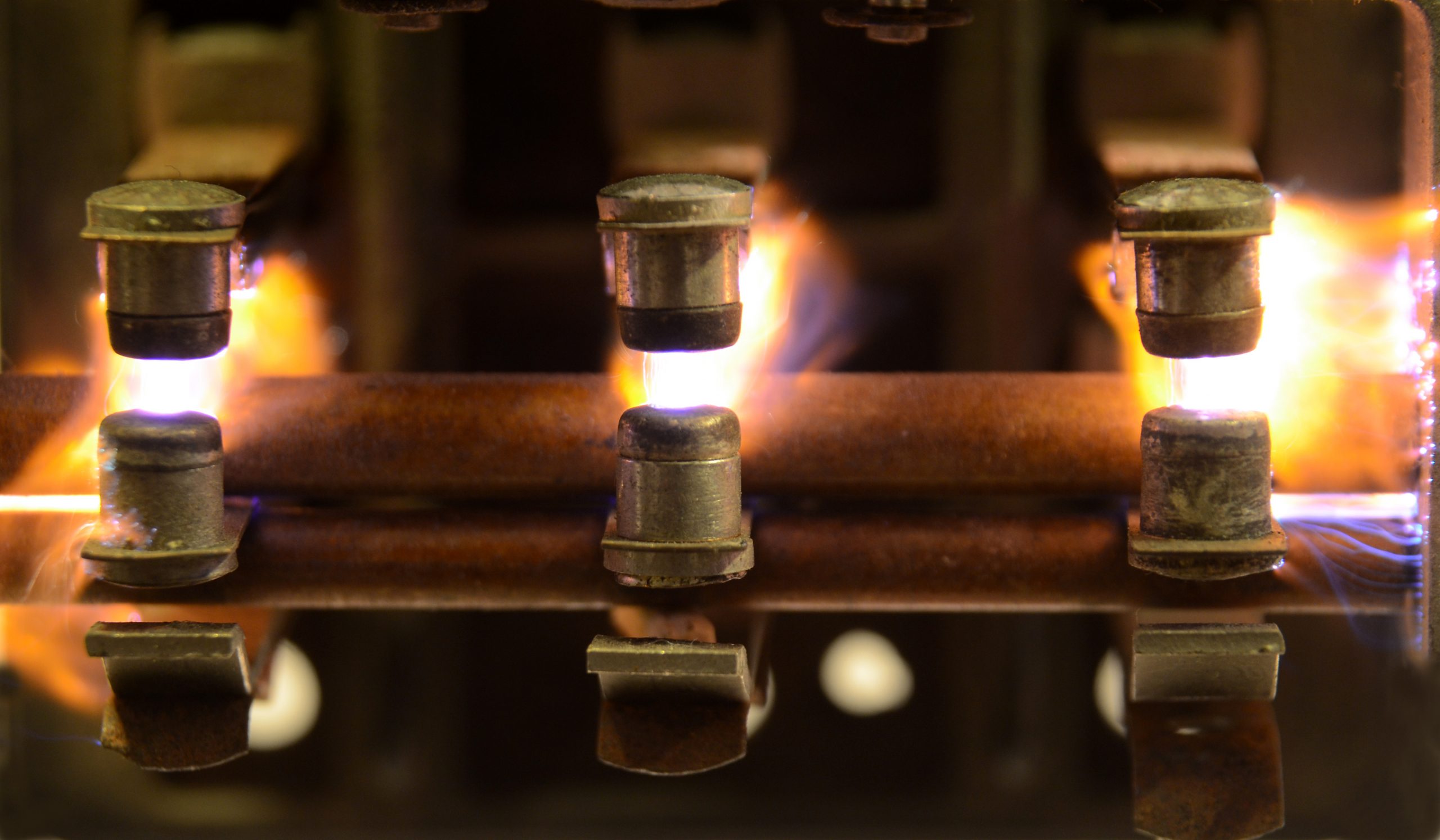

An electrical fuse

When electricity passes through the circuit (and fuse), it heats up the wire. But if the current running through the circuit gets too high the wire overheats and disintegrates, breaking the circuit and preventing the wires and devices attached to it from being damaged. When a fuse like this breaks in a plug or a fuse box it must be replaced. A circuit breaker, however, can carry out this task again and again.

Instead of a piece of wire, circuit breakers use an electromagnetic switch. When the circuit breaker is on, the current flows through two points of contact. When the current is at a normal level the adjacent electromagnet is not strong enough to separate the contact points. However, if the current increases to a dangerous level the electromagnet is triggered to kick into action and pulls one contact point away, breaking the circuit and opening the circuit breaker.

Another approach to fuses is using a strip made of two different types of metals. As current increases and temperatures rise, one metal expands faster than the other, causing the strip to bend and break the circuit. Once the connection is broken the strip cools, allowing the circuit breaker to be reset.

This approach means the problem on the circuit can be identified and solved, for example by unplugging a high-voltage appliance from the circuit before flipping the switch back on and reconnecting the circuit.

Protecting generators at grid scale

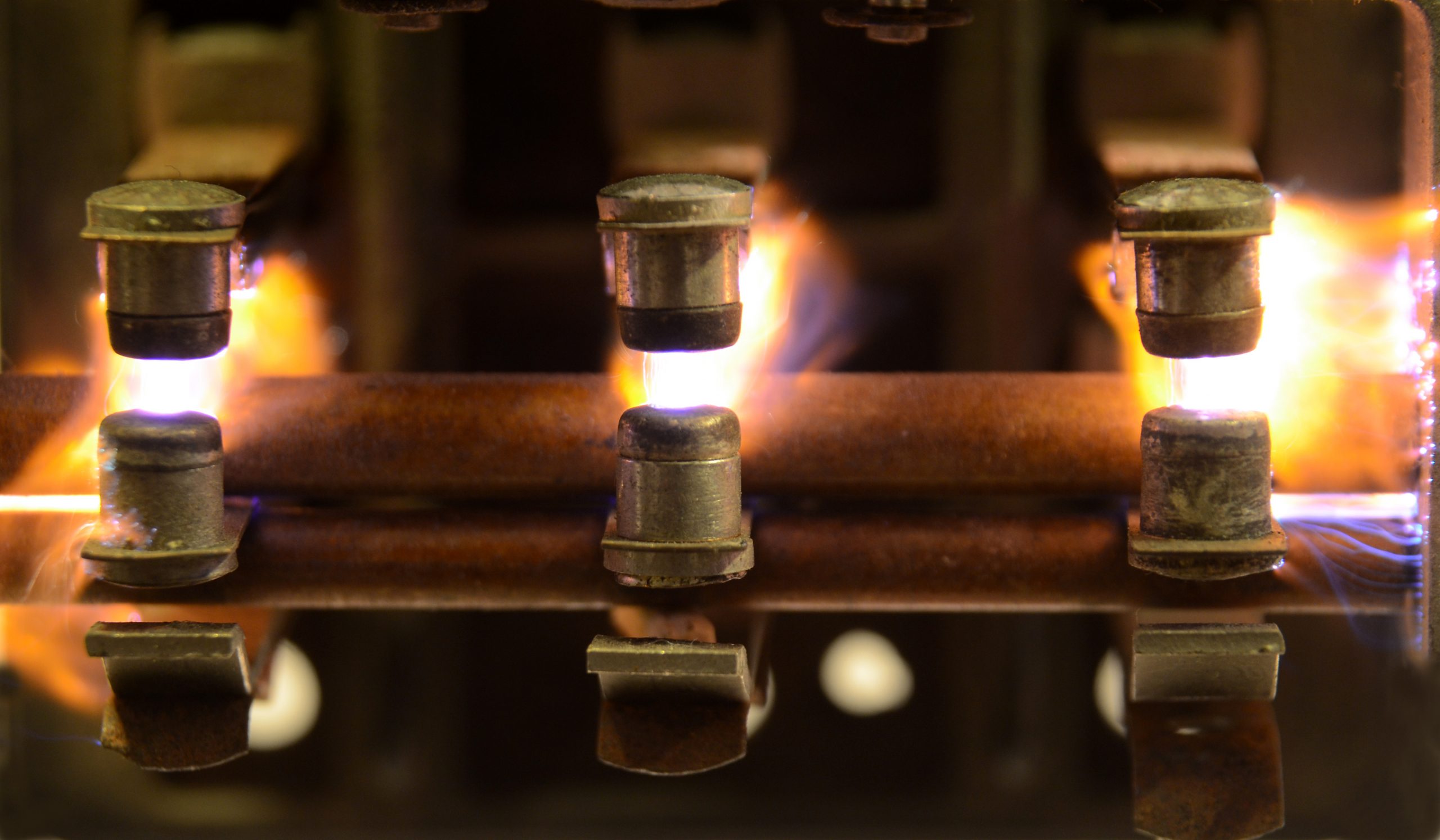

Power circuit breakers for a high-voltage network

Circuit breakers are important in residential circuits, but at grid level they become even more crucial in preventing wide-scale damage to the transmission system and electricity generators.

If part of a transmission circuit is damaged, for example by high winds blowing over a power line, the current flow within that circuit can be disrupted and can flow to earth rather than to its intended load or destination. This is what is known as a short circuit.

Much like in the home, a short circuit can result in dangerous increases in current with the potential to damage equipment in the circuit or nearby. Equipment used in transmission circuits can cost millions of pounds to replace, so it is important this current flow is stopped as quickly as possible.

“Circuit breakers are the light switches of the transmission system,” says Beardsall.

“They must operate within milliseconds of an abnormal condition being detected. However, In terms of similarities with the home, this is where it ends.”

Current levels in the home are small – usually below 13 amps (A or ampere) for an individual circuit, with the total current coming into a home rarely exceeding 80A.

In a transmission system, current levels are much higher. Beardsall explains: “A single transmission circuit can have current flows in excess of 2,000A and voltages up to 400,000 Volts. Because the current flowing through the transmission system is much greater than that around a home, breaking the circuit and stopping the current flow becomes much harder.”

A small air gap is enough to break a circuit at a domestic level, but at grid-scale voltage is so high it can arc over air gaps, creating a visible plasma bridge. To suppress this the contact points of the circuit breakers used in transmission systems are often contained in housings filled with insulating gases or within a vacuum, which are not conductive and help to break the circuit.

A 400kV circuit breaker on the Drax Power Station site

In addition, there will often be several contact points within a single circuit breaker to help break the high current and voltage levels. Older circuit breakers used oil or high-pressure air for breaking current, although these are now largely obsolete.

In a transmission system, circuit breakers will usually be triggered by relays – devices which measure the current flowing through the circuit and trigger a command to open the circuit breaker if the current exceeds a pre-determined value. “The whole process,” says Beardsall, “from the abnormal current being detected to the circuit breaker being opened can occur in under 100 milliseconds.”

Circuit breakers are not only used for emergencies though, they can also be activated to shut off parts of the grid or equipment for maintenance, or to direct power flows to different areas.

A single circuit breaker used within the home would typically be small enough to fit in your hand. A single circuit breaker used within the transmission system may well be bigger than your home.

Circuit breakers are a key piece of equipment in use at Drax Power Station, just as they are within your home. Largely un-noticed, the largest power station in the UK has hundreds of circuit breakers installed all around the site.

A 3300 Volt circuit breaker at Drax Power Station

“They provide protection for everything from individual circuits powering pumps, fans and fuel conveyors, right through to protecting the main 660 megawatt (MW) generators, allowing either individual items of plant to be disconnected or enabling full generating units to be disconnected from the National Grid,” explains Beardsall.

The circuit breakers used at Drax in North Yorkshire vary significantly. Operating at voltages from 415 Volts right up to 400,000 Volts, they vary in size from something like a washing machine to something taller than a double decker bus.

Although the size, capacity and scale of the circuit breakers varies dramatically, all perform the same function – allowing different parts of electrical circuits to be switched on and off and ensuring electrical system faults are isolated as quickly as possible to keep damage and danger to people to a minimum.

While the voltages and amount of current is much larger at a power station than in any home, the approach to quickly breaking a circuit remains the same. While circuits are integral parts of any power system, they would mean nothing without a failsafe way of breaking them.

“Take the opportunity! We’re very lucky to have the chance to complete apprenticeships while working.”

“Take the opportunity! We’re very lucky to have the chance to complete apprenticeships while working.”