Over the last century, Scottish hydro power has played a major part in the country’s energy make up. While today it might trail behind wind, solar and biomass as a source of renewable electricity in Great Britain, it played a vital role in connecting vast swathes of rural Scotland to the power grid – some of which had no electricity as late as the 1960s. And all by making use of two plentiful Scottish resources: water and mountains.

But the road to hydro adoption has been varied and difficult, travelled on by brave death-defying construction workers, ingenious engineers and the inspirational leadership of a Scottish politician.

To trace where the history of Scottish hydropower began, we need to go back to the end of the 19th Century and to the banks of Loch Ness.

Loch Ness, Scottish Highlands

From abbeys to aluminium

It was on the shores of Loch Ness that one of the first known hydro-electric schemes was built at the Fort Augustus Benedictine abbey. The scheme provided power to the monks living there as well as 800 village residents – though legend has it that their lights went dim every time the monks played their organ.

However, it was the British Aluminium Company, formed in 1894, that first realised the huge potential of Scotland’s steep mountains, lochs and reliably heavy rainfall to generate substantial amounts of hydro power. In need of a reliable source of electricity to help turn raw bauxite into aluminium, the firm established a hydro-electric plant and smelting works at Foyers and Loch Ness. Several similar schemes to support the aluminium industry soon appeared around the country.

But it took another 20 years for the first major hydro-power project to supply electricity to the public to emerge.

In 1926, the Clyde Valley Electrical Power Co. opened the Lanark Hydro Electric Scheme, which used energy from the River Clyde’s flow to create power. Now owned by Drax, it still has a generation capacity of 17 MW – enough to supply more than 15,000 homes.

River Clyde, Lanark

It was quickly followed by power stations at Rannoch and Tummel in the Grampian mountains and, in 1935, by what became a highly influential scheme in the history of Scottish hydro power at Galloway.

Drawing enough energy from local rivers to support five generating power stations, the project was the largest run-of-the-river scheme ever created. Architecturally, it also set the tone for later projects with stylised dams and modernist turbine halls.

A fairer share of power for the Highlands

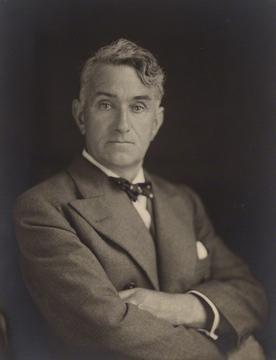

The Galloway scheme supplied energy to a wide area, too, including parts of the central Highlands. Scottish Labour MP Tom Johnston, a staunch socialist and Scottish patriot saw how this new power source could provide massive benefits to northern communities. In the early 1940s, only an estimated one in six Scottish farms and one in a hundred small land crofts had electricity.

In 1941, Johnston became Scotland’s Minister for State with a vision, as he put it, to create “large-scale reforms that might mean Scotia Resurgent”. Expanding hydro power was a priority.

Tom Johnston MP

Two years later, he formed the North of Scotland Hydro-Electric Board (NSHEB). Its aim was to create several new schemes, including at Tummel and Loch Sloy, that would supply the national grid and bring electricity to more rural Scottish areas.

The projects were met with fierce opposition from landowners and local pressure groups who feared new dams and power stations would ruin the countryside and bring unwelcome industrialisation.

Public enquiries followed, but the board’s promises that the developments would be sensitive to the environment and bring cheap electricity in areas such as the Isle of Skye and Loch Ewe eventually won the day.

Thousands of local men, as well as German and Italian former prisoners of war, were drafted in to work on the projects.

Among the most courageous were workers known as ’Tunnel Tigers’ who blasted away rock using handheld drills and gelignite to create water channels and underground chambers, including at Drax’s Cruachan pumped storage hydro station.

Deaths caused by everything from blast injuries to fires were common. The men also had to cope with incessant rain and cold, and were housed in bleak military-style camps. With little to do in their spare time, besides drink, fights would break out regularly.

But the financial rewards were enormous, with wages up to ten times higher than labourers employed on Highland estates could expect.

Glenlee penstocks

The future takes shape

The board’s first small projects were completed in 1948 at Morar and Nostie Bridge, supplying electricity to areas including parts of Wester Ross. Catherine Mackenzie, a local widow, performed the Morar opening ceremony, reportedly declaring: “Let light and power come to the crofts.”

Bigger schemes were plagued by problems. Conveyor belts had to be built to transport stone across 1.75 miles of moor during construction at Sloy, for instance, and there were frequent stone and timber shortages.

But Sloy eventually opened in 1950, the largest conventional hydro electrical power station in Great Britain with an installed capacity of 128 MW. It would be followed by major schemes at Glen Affric and Loch Shin.

By the mid Sixties, the Board had built 54 main power stations and 78 dams. Northern Scotland was now 90% connected to the national grid. Hydro Board shops began popping up on high streets, selling appliances and collecting bill payments.

Tom Johnston died in 1965, aged 83. The Provost of Inverness declared: “No words can say how grateful we are.”

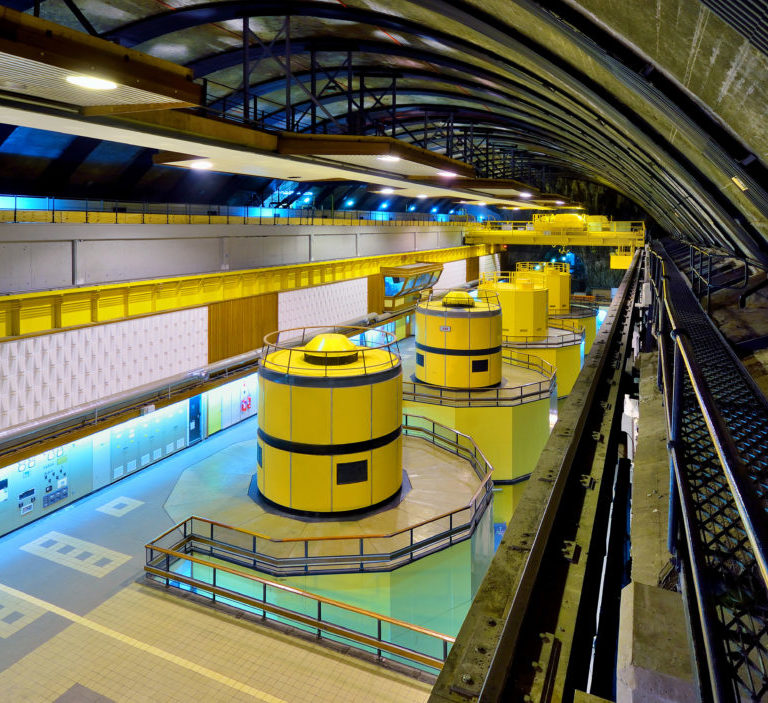

Loch Awe beside Cruachan Power Station

That same year, the world’s then largest reversible pumped storage power station opened at Cruachan. During times of low electricity demand, its turbines pump water from Loch Awe to the reservoir above. When demand rises, the turbines reverse, and water flows down to generate power. A similar scheme opened at Foyes in 1974.

Glendoe, near Loch Ness, was the most-recent major hydro scheme to be built. Opening in 2009, it has a generation capacity of 100 MW.

There are plans for a pumped storage scheme at Coire Glas, with a storage capacity of 30 GWh– more than doubling Great Britain’s current total pumped storage capacity. Drax’s Cruachan Power Station could also be expanded.

In recent years, however, the real growth has been in smaller hydro-electric schemes that may power just one or a handful of properties – with more than 100 MW of such generation capacity installed in the Highlands since 2006.

Boosting the environment and economy

Scotland now provides 85% of Great Britain’s hydro-electric resource, with a total generation capacity of 1,500 MW. Improved power supplies have attracted more industry to the Highlands, without seriously altering its character. And access roads created during hydro-power schemes’ construction have opened up remote areas to tourism.

For many, the dams built by NSHEB are among the greatest construction achievements in post-war Europe and remain an essential part of Great Britain’s attempts to move towards a low-carbon energy future.