There is an ongoing debate about forests’ contribution to fighting the climate crisis.

Forests can act as substantial and effective tools for carbon sequestration during a high growth phase. They can also function as significant and extensive carbon storage areas during maturity and throughout multiple stages of the age class cycle, if managed effectively at a landscape level. Or, they can be emitters of carbon if over-harvested, subject to fire, storm, pest or disease damage.

Different age class forest stands in Louisiana

In a natural state, forests will go through each of these life phases: rapid early growth; maturity and senescence; damage, decay and destruction through natural causes. Then they begin the cycle again, absorbing and then emitting carbon dioxide (CO2) in a continual succession.

Recently, loud voices have argued against forest management per se; against harvesting for wood products in particular, suggesting that this reduces both forest carbon stocks and sequestration capacity.

Pine cut in into wood for different wood products markets in Louisiana. Big, thick, straight higher value sections go to sawmills and smaller and misshapen low-grade wood not suitable for timber production is sold to pulp, paper or wood pellet mills.

Many foresters consider that this is just not correct. In fact, the opposite is true. Research and evidence clearly support the foresters’ view. Active forest management, when carried out appropriately, actually increases the amount of carbon sequestered, ensures that carbon is stored in solid wood products, and provides substantial savings of fossil fuels by displacing other high carbon materials (e.g. concrete, steel, brick, plastic and coal).

Oliver et al.(2014)[1] compared the impact of forest harvesting and the use of wood products to substitute other high-carbon materials, concluding that: ‘More CO2 can be sequestered synergistically in the products or wood energy and landscape together than in the unharvested landscape. Harvesting sustainably at an optimum stand age will sequester more carbon in the combined products, wood energy, and forest than harvesting sustainably at other ages.’

This research demonstrated that an increase in the use of structural timber to displace concrete and steel could lead to substantial emissions savings compared to unharvested forest. The use of wood for energy is an essential component of this displacement process, although it is important to use appropriate feedstocks. Burning wood that could be used for structural timber will not lead to a positive climate impact.

The message here is to manage working forests for optimum sawlog production for long-life solid wood products and utilise the by-products for energy where this is the most viable market, this provides the best all-round climate benefit.

What happens when you close the gate

Closing the forest gate and stopping all harvesting and management is one option being championed by some climate change campaigners. There is certainly a vital role for the preservation and protection of forests globally: primary and virgin forests, intact landscapes, high biodiversity and high conservation value areas all need to be protected.

That doesn’t necessarily mean that there is no forest management. It should mean careful and appropriate management to maintain and ensure the future of the resource. In these cases, management is with an objective to reduce the risk of fire, pests and disease, rather than for timber production.

Globally, we need better governance, understanding and implementation of best practice to achieve this. Forest certification and timber tracing systems are a good start. This can equally apply to the many hundreds of millions of hectares of ‘working forest’ that do not fall into the protection categories; forests that have been managed for many hundreds of years for timber production and other purposes. Harvesting in these forests can be more active, but governance, controls and the development of best practice are required. Better management not less management.

During the 1970s there was a significant change of policy in the US, aimed at removing massive areas of publicly owned forest from active management – effectively closing the gate. The drivers behind this policy were well meaning; it was intended to protect and preserve the habitat of endangered species, but the unintended consequences have also had a substantial impact. In the 1970s little thought was given to the carbon sequestration and storage potential of forests and climate change was not at the top of the agenda.

The west coast of the US was most substantially affected by these changes, more than in the US South, but the data below looks at the example of Mississippi which is primarily ‘working forest’ and 88% in private ownership.

Pine trees in Mississippi working forest

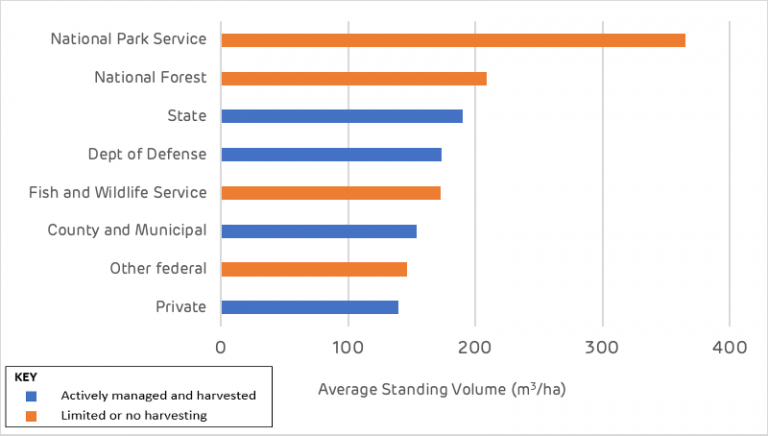

This is the location of Drax’s Amite pellet mill. The charts below show an interesting comparison of forest ownership in Mississippi where limited or no harvesting takes place and where active management for timber production occurs. In the short term the total volume of timber stored per hectare is higher where no harvesting occurs. This makes sense since the forest will keep growing until it reaches its climax point and succumbs to fire, pest or disease.

Average standing volume per unit area in the private sector, where active management occurs, is the lowest as timber is periodically removed for use in solid wood products. Remember that the Oliver et al. analysis (which does not include re-growth), showed that despite a short-term reduction in forest carbon, the total displacement of high-carbon materials with wood for structural timber and energy leads to a far higher emissions saving. It is better to have a lower stock of carbon in a working forest and to be continually sequestering new carbon for storage in solid wood products.

Average standing volume per acre by ownership class, Mississippi[2]

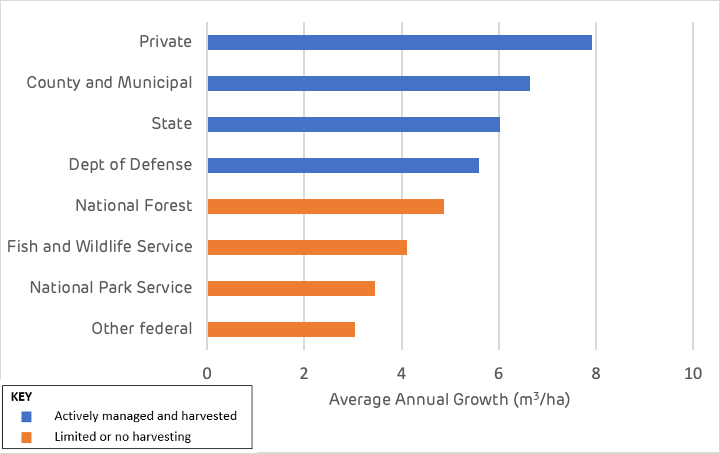

Average growth rates per acre by ownership class, Mississippi[3]

We know that forests are not being ‘lost’ and that the overall storage of carbon is increasing. For example, the Drax catchment area analysis for the Amite biomass wood pellet plant showed an increase in forest area of 5,200 ha and an increase in volume of 11 million m3 – just in the area around the pellet mill. But what happens to protected forest area, the forest reserve with limited or no harvesting?

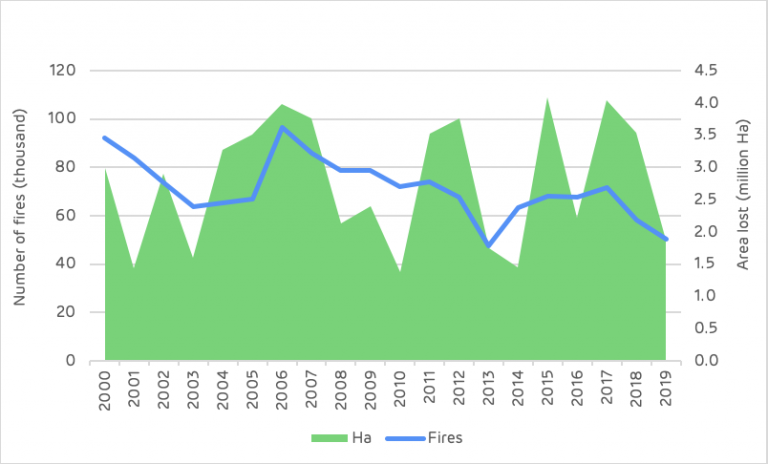

Over the last 20 years the average annual loss of forest to wildfire in the US has been 2.78 million ha per year (the same as the UK’s total area of productive forest). According to the USFS FIA database the average standing volume of forests in the US is 145 m3 per ha (although in the National Park land this is 365 m3 per ha). Therefore, wildfires are responsible for the average annual combustion of 403 million m3 of wood p.a. (equal to the total annual wood harvest of the US) or 2.5 billion m3 if entirely in National Parks.

One cubic metre equates to a similar quantity of CO2 released into the atmosphere each year, therefore wildfires are responsible for between 407 million and 2.5 billion tonnes of CO2 emissions in the US each year[4].

Wildfires in the US

Starrs et al. (2018)[5] demonstrated that the risk of wildfire was significantly higher in federally owned reserved forest (where harvesting and management were restricted), compared to privately owned forests with active management.

In California, the risk of wildfire in federal forest (2000-15) was almost double the risk in private forests where both had State firefighting resources. The risk of fires in federal lands had increased by 93% since 1950-66, compared to only 33% in non-federal forests, due to the change in forest management practice in the 1970s.

Forest fire in California

Closing the gate means that the carbon stock is maintained and grows in the short term, but there is no opportunity for carbon to be stored in solid wood products, no high-carbon materials are displaced (concrete, steel and fossil fuels) and the rate of sequestration declines as the forest ages. Eventually the forest will reach its natural climax and die, releasing all of that carbon back into the atmosphere. The managed forest, by contrast, will have a lower standing volume at a certain point in time, but will be in a continual cycle of sequestration, storage and regrowth – with a much lower risk of fire and disease. If managed correctly, the rate of growth and standing volume will also increase over time.

How should we manage the forest

Forests are extremely variable, there are a vast variety of tree species, soil, geological features, water regimes, temperature, climate and many other factors that combine to make unique ecosystems and forest landscapes. Some of these are rare and valuable for the exceptional assemblages they contain, some are commonplace and widespread. Some are natural, some man-made or influenced by human activity.

Forests have many important roles to play and careful management is required. In some cases that management may be protection, preservation and monitoring. In other cases, it may be active harvesting and planting to optimise growth and carbon storage.

Cypress forests in the Atchafalaya Basin in Louisiana are an example of a forest landscape where the suitable management practice is protection, preservation and monitoring

For each forest type and area, we need to recognise the highest or best purpose(s) for that land in the objectives set and carefully plan the management to optimise and sustain that value. The primary value could be in species and habitat diversity or rarity; provision of recreation and aesthetic value; production of timber, forest products and revenue generation; carbon sequestration and storage; water management and other ecosystem benefits.

Most likely it will be a combination of several of these benefits. Therefore, best management practice usually involves optimising each piece of forest land to provide the most effective combination of values. Forests can deliver many benefits if we are sensible about how we manage them.

In a recent study Favero et al. (2020)[6] concluded that: Increased bioenergy demand increases forest carbon stocks thanks to afforestation activities and more intensive management relative to a no-bioenergy case. Some natural forests, however, are converted to more intensive management, with potential biodiversity losses…the expanded use of wood for bioenergy will result in net carbon benefits, but an efficient policy also needs to regulate forest carbon sequestration.