Scientific research isn’t all test tubes and lab coats – sometimes it’s bark and soil. It might be a world away from the image of a sterile laboratory, but the world of forestry is one that has seen significant scientific progress since the 18th century, when it first emerged as an area of study.

The development of environmental sciences and ecology, as well as advances in biology and chemistry mean there are still new discoveries being made – from trees’ ability to ‘talk’ to each other through underground fungi networks, to forests’ positive impact on mental health.

Fostering greater awareness and understanding of fragile forest ecosystems such as the cypress swamps of the Atchafalaya Basin in Louisiana, forestry has also allowed for the improvement of working forests — landscapes planted to grow wood for products and services that often avoid the use of fossil fuel-based alternatives.

Cypress forests in the Atchafalaya Basin in Louisiana are an example of a forest landscape where the suitable management practice is protection, preservation and monitoring

By enhancing the genetic stock, tree breeding ensures seedlings and plants are better adapted to their environment (soil, water, temperature, nutrient level, etc.). Science can now help trees to grow more quickly, storing more carbon. It can also give trees better form — straighter trees can produce more saw-timber which can, in turn, lock more carbon in buildings made predominantly or partially of the natural, renewable product that wood is.

But more than just uncovering surprising insights into the ins and outs of our natural world, forestry science is contributing to a far bigger goal: tackling climate change.

The science of forests

When the scientific study of forests first emerged in 18th century Germany, it was with the aim of sustainability in mind. Industries were concerned forests wouldn’t be able to provide enough timber to meet demand, so research began into how to manage them responsibly.

Forestry today encompasses much more than just providing saw logs and the research going into it remains driven by the same goal: to ensure sustainability. Its breadth, however, has grown.

The UK Forestry Commission’s research and innovation strategy highlights the scope it should cover: “It must be forward-looking to anticipate long-term challenges, strategic to inform emerging policy issues, and technical to support new and more efficient forestry practices.”

Pine trees grown for planting in the forests of the US South where more carbon is stored and more wood inventory is grown each year than fibre is extracted for wood products such as biomass pellets

Being able to deliver on this breadth has relied on rapid advances in technology – including taking forestry research into space.

The technology teaching us about trees

As in almost every industry, one of the major drivers of change in forestry is data, and the ability to collect data from forests is getting more advanced.

At ground level, techniques like ‘sonic tomography’ allow foresters and researchers to ‘see’ inside trees using sound waves, measuring size, decay and overall health. This, in turn, offers a bigger picture of forests’ wellbeing.

At the other end of the scale, satellites and mapping technology are playing a major role in advancing a macro view of the world’s forests – particularly in how they change over time. As well as a potent tool in monitoring and helping fight deforestation, satellite images have revealed there is nine per cent more forest on earth than previously thought.

Space satellite with antenna and solar panels in space against the background of the earth. Image furnished by NASA.

The European Space Agency’s Earth Explorer programme will go a step further and use radar from satellites to penetrate the forest canopy, measuring tree trunks and branches rather than just the area covered by forest. Determining the volume of wood in forests around the planet will effectively enable researchers to ‘weigh’ the world’s forest biomass.

The masses of data these advances in tech are providing, is playing a major role in how we manage our forests, including how we can use them to fight global warming.

Taking on the climate crisis

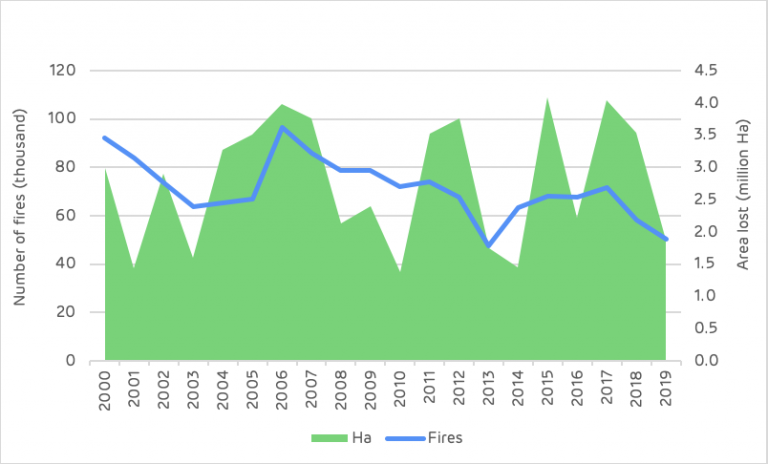

Forests are one of the key defences against climate change – so much so they’re included in the Paris Agreement. Trees’ abilities to absorb carbon dioxide (CO2) has long been established knowledge. Thanks to what climate scientists call IAMs or integrated assessment models, we now know how much they can extract from the atmosphere and how long they can continue to do so, as CO2 levels rise.

One optimistic hypothesis says trees will take in more CO2, as the levels rise. To test this, researchers in the UK are blasting controlled sections of a forest with CO2 to increase its density by 40%, representing expected global levels by 2050. By tracking how trees react they hope to highlight the role they can play as carbon sinks.

Science also suggests they could not only help slow climate change, but actively fight it. The research considers that as well as absorbing CO2, trees are reported to emit gases that reflect sunlight back into space, ultimately contributing to global cooling.

However, planting more trees isn’t necessarily the only answer. In places experiencing drought such as the western US, thinning forests can reduce competition and allow healthier trees capable of absorbing more oxygen to flourish.

The increasing body of research on forests’ impact on climate change could prove vital in shaping both the forestry industry and national governments’ approaches forests. However, as a science, forestry could be considered to be in its infancy. At this crucial time for the planet’s future, forestry is becoming one of the most important environmental sciences, but a lot more attention, investment and research and development are required if we are able to fully understand and manage the world’s forest resources. We have barely scratched the surface.