Key takeaways:

- Across the globe, wildfires are increasing in size and frequency, driven by the effects of climate change.

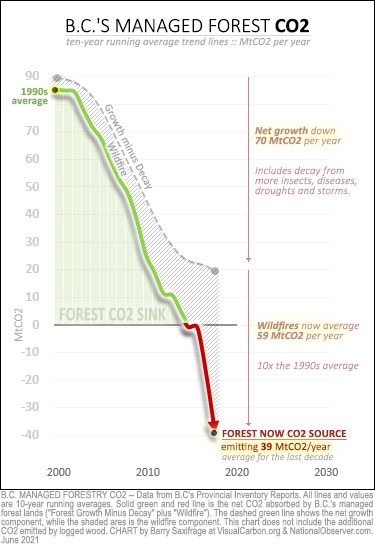

- In places like British Columbia, surging wildfires have meant that in recent years, some forests have been emitting more carbon than they have been able to absorb.

- British Columbia can serve as an example for where wildfire mitigation occurs, to reduce the risk of threats to communities and forest ecosystems.

- An essential step is reducing potential fuel for fires by removing flammable material on the forest floor and dead standing trees. The market for biomass encourages the removal of excess fibre which could become fuel for dangerous wildfires.

- Collaboration between government, industry and First Nations in British Columbia ensures that forests are managed and protected to remain useful resources for all.

Forest fires are nothing new. Temperate forests throughout the world have evolved with fire over millions of years, and a certain amount of fire is inevitable and necessary to maintain the overall health of many types of forests.

But as global temperatures have increased in recent decades, so have the size and recurrence of wildfires. After Australia saw record heat in the summer of 2020, a series of fires across the continent burned an unprecedented 58,000 square kilometres (km2), an area larger than Costa Rica. While in 2022, Europe saw 7,850 km2 of forest destroyed in a single scorching summer, more than double the amount burned in an average fire season.

In addition to the effects of climate change, catastrophic wildfires have also prevailed in response to widespread fire suppression, when methods were sought to increase the resiliency of landscapes to fire and change forest stand characteristics. This has in turn led to thicker and denser forests, and increased fuel loading.

Prior to fire suppression, wildfires would have burned vast areas. In some cases, lower-intensity, stand-maintaining wildfires would naturally keep the forest understory clear of fuel loads. Fire suppression has instead led to increasing density in the forest understory, and when fire inevitably returns to those forest stands it creates conditions for high-intensity, stand-replacing fire events.

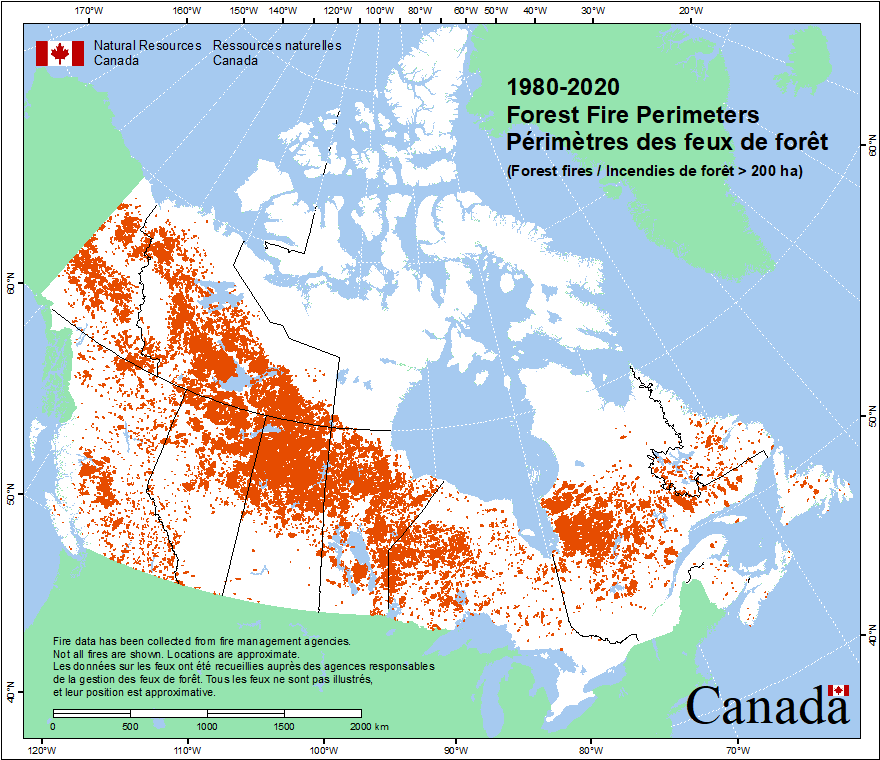

In Canada, British Columbia has not escaped these trends of larger fires.

About 64% of the province, more than 60,000 km2, is forested. This makes it particularly vulnerable to wildfire. In 2021 more than 1,600 separate fires burned nearly 8,700 km2 of land in the province, displacing thousands of people from their homes and wildlife from their habitats. Wildfires in the region also now average around 59 MtCO2 of emissions per year, 10x times the 1990s average, meaning that in recent years, British Columbia’s forests have been emitting more carbon than they have been able to absorb, becoming a source of CO2 rather than a sink.

In a region where forests are an important part of life, as well as an essential economic resource for rural communities, protecting forests from intense wildfires, and mitigating the effects, is crucial.

Delivering proactive management against wildfire

Managing forests to make them more resilient to wildfires requires careful management and collaboration between government, industry, communities, and First Nations.

The British Columbian government’s 2022 budget included CA$359 million in new funding to protect British Columbia from wildfires, including CA$145 million over three years to help move the BC Wildfire Service from a reactive to a proactive model. This means year-round work on four pillars of emergency management: prevention and mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery.

The biomass industry has an important role to play in this work, incentivising fire mitigation and forest management which help protect forests for local communities to use and enjoy, as well as harvesting and regenerating fire-damaged land.

How forest management can protect forests against wildfires

For thousands of years, First Nations used small fires to clear forests, improving habitat for hunting and reducing the chance of large, uncontrollable fires.

While fire may be a natural part of the province’s landscape, active human management can help reduce the damage fires cause One key step is to remove the fuels that cause fires to burn and spread.

Fuels that feed wildfires consist of any burnable materials found on forest floors, ranging from grasses, dead leaves, and small trees to logs, stumps, and branches. Another fuel source are juvenile seedlings, sometimes called “ladder fuels” which move the forest fire from the ground into the forest canopy which often leads to fires that are much more severe and harder to suppress. Outbreaks of pests, like mountain pine beetle, also contribute to fuel loads, leaving large areas of dead wood.

Material accumulated on the forest floor over time can eventually become a source of what’s called ladder fuel that enables a relatively small fire to reach the forest canopy, burning higher, faster, and farther. These fuel loads, coupled with hotter temperatures and more frequent drought, make today’s fires more likely to burn larger and more intensely than their historic counterparts.

Removing sources of fuel and thinning the density of forest stands are sustainable management practices that can help mitigate the risk of the most damaging types of fires.

“When there’s less fuel to consume, future fire events will be lower in intensity,” says Mike Thomas, Regional Biomass Purchaser for Drax Canada. “And because they’re at low levels of intensity, the existing trees will live through the fire.”

However, removing fuel sources from forests can be expensive and historically has not been a priority for forestry operations focused on producing lumber and solid wood products. This makes biomass an important market, serving as a fibre purchaser for the low-grade wood removed in fire mitigation operations.

“Forest mitigation projects are very labour intensive and can be very expensive,” says Thomas. “The smaller material that we purchase from operators for pellet plants also helps to complete the projects. Without the biomass market, there would be less incentive to carry out these fire mitigation operations.”

Collaboration is key to lowering the amount of fuel in a forest

The type of sustainable forest management practices that reduce fuel loads require effort, know-how, and even the right market conditions. The key to implementing these practices is collaboration, between industry, government, and First Nations.

One example is the joint venture between the Tŝideldel First Nation (TFN) and the Tl’etinqox First Nation. The resulting company, called Central Chilcotin Rehabilitation (CCR), is involved in forestry projects, including fire rehabilitation, in the two groups’ traditional territories.

Forest area infected with the mountain pine beetle in British Columbia, Canada

The traditional land of Tŝideldel First Nation is largely lodgepole pine forest, which has been hard hit by mountain pine beetles and subject to frequent burning. In response, the Tŝdeldel have spearheaded several projects to remove dead standing trees and low-grade wood to reduce overall fuel load. Such projects aim to make the damaged landscapes productive, valuable resources once again.

Drax’s partnership with the Tŝideldel provides a crucial market for dead and low-grade wood removed from damaged forests, making it possible to finance forest management operations and reduce the chances of devastating wildfires.

A proactive example for the future

British Columbia offers an example of how smart, proactive forest management can play an important role in reducing the risk of catastrophic fires and making them more resilient to the effects of climate change.

Therefore, by working with the wider forestry sector, the biomass industry can help to facilitate important wildfire mitigation projects, ensuring forests and communities are protected, and all those who use them can continue to depend on them as a vital resource.