How long do your electrical devices last? We’re not talking about battery life, but the overall lifetime of the items we use every day that are powered by electricity.

It’s accepted that today’s electrical devices have short life spans, in part a symptom of rapidly evolving technology fuelling the need for constant consumer updates and in part a result of planned obsolescence (devices being manufactured to fail within a set number of years to encourage repeat purchases). Electrical devices aren’t purchased with the belief they will last a lifetime.

But it hasn’t always been this way. Before rapid technological development and the rise of fast consumerism, devices were built to last.

Over the relatively short history of electrical appliances, there are tools and equipment that have operated for decades. Some of these remain in operation today with hardly any alterations, but for a few tweaks here and there to upgrade or preserve.

Built to last, here are a few of the longest running electrical inventions.

The Oxford Electric Bell located in the Clarendon Laboratory, University of Oxford.

1840 – The Oxford Electric Bell

The Oxford Electric Bell is not your typical bell – not just in how it looks, but in the fact it has been in constant operation since the mid 19th Century. It consists of two primitive batteries called ‘dry piles’ with bells fitted at each end and a metal ball that vibrates between them to very quietly, continuously ring.

Its original purpose is unidentified, but what is known is that the bell is the result of an experiment put on by the London instrument-manufacturing firm Watkins and Hill in 1840. Acquired by Robert Walker, a physics professor at the University of Oxford in the mid 1800s, it’s displayed at Oxford’s Clarendon Laboratory which explains why it’s also known as the Clarendon Pile.

The exact make-up of the dry piles is unknown, as no one wants to tamper with them to investigate their composition out for fear of ending the bell’s 179-year-long streak. As a result, confusion remains as to why The Oxford Electric Bell has remained in operation for so long.

Souter Lighthouse, Tyneside, England.

1871 – Souter Lighthouse in South Shields, UK

The lamp in the Souter lighthouse, situated between the rivers Tyne and Wear, was the most advanced of its day when it was first constructed. Designed to use an alternating electric current, it was the first purpose-built, electrically powered lighthouse in the world. Although no longer in operation today, it ran unchanged for nearly 50 years.

The light was generated using carbon arc lamps, and it originally produced a beam of red light that would come on once every five seconds.

Souter’s original lamp operated unchanged from 1871 to 1914, when it was replaced by more conventional oil lamps. It was altered again to run on mains electric power in 1952 and was finally deactivated in 1988.

1896 – The Isle of Man’s Manx Electric Railway

Tourism hit the Isle of Man in the 1880s and with it came the construction of hotels and boarding houses. Two businessmen saw this as an opportunity to purchase a large estate on the island and develop it into housing and a pleasure development. The Manx Parliament approved the sale in 1892 on one condition: that a road and a tramway be built to give people access.

Snaefell mountain railway station, Isle of Man.

It was decided that the tram would be electric, and work began in the spring of 1893, with the tram system up and running by September of that year. Although the track and its cars have been extended and updated over time, the first three cars remain the longest running electric tramcars in the world.

Photograph by Dick Jones (centennialbulb.org)

1902 – The Centennial Bulb

The unassuming Centennial Bulb has been working in the Livermore, California Fire Department for 117 years. The bulb was first installed in 1902 in the department’s hose cart house, but was later moved to Livermore’s Fire Station 6, where it has been illuminated for more than a million hours.

Throughout its life the Centennial Bulb has seen just two interruptions: for a week in 1937 when the Firehouse was refurbished, and in May 2013 when it was off for nine and a half hours due to a failed power supply. Made by the Shelby Electric Company, the hand-blown bulb previously shone at 60 watts but has since been dimmed to 4 watts.

While this means it isn’t able to actually illuminate much, it is a reminder that despite the disposable nature of many modern electrical devices, it’s possible to build electrical items that last.

While the constant development of battery and charging technology will likely mean this prediction will come down, there are some theories as to how the country will need to deal with this rapid growth. One of these is to actually turn down the electricity surging through charging points at certain points to prevent widespread blackouts.

While the constant development of battery and charging technology will likely mean this prediction will come down, there are some theories as to how the country will need to deal with this rapid growth. One of these is to actually turn down the electricity surging through charging points at certain points to prevent widespread blackouts.

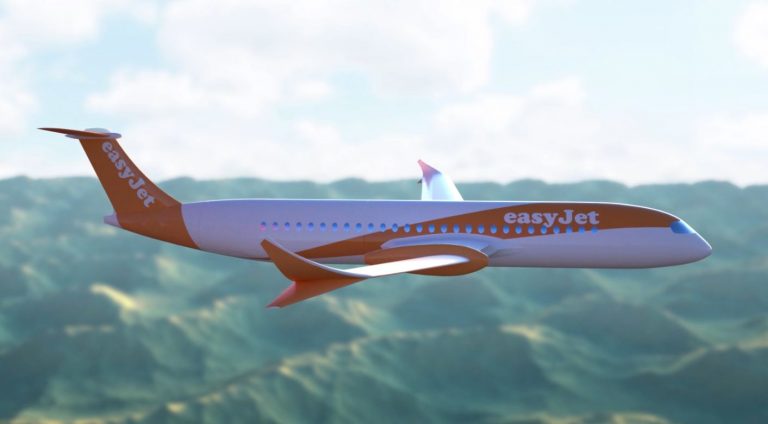

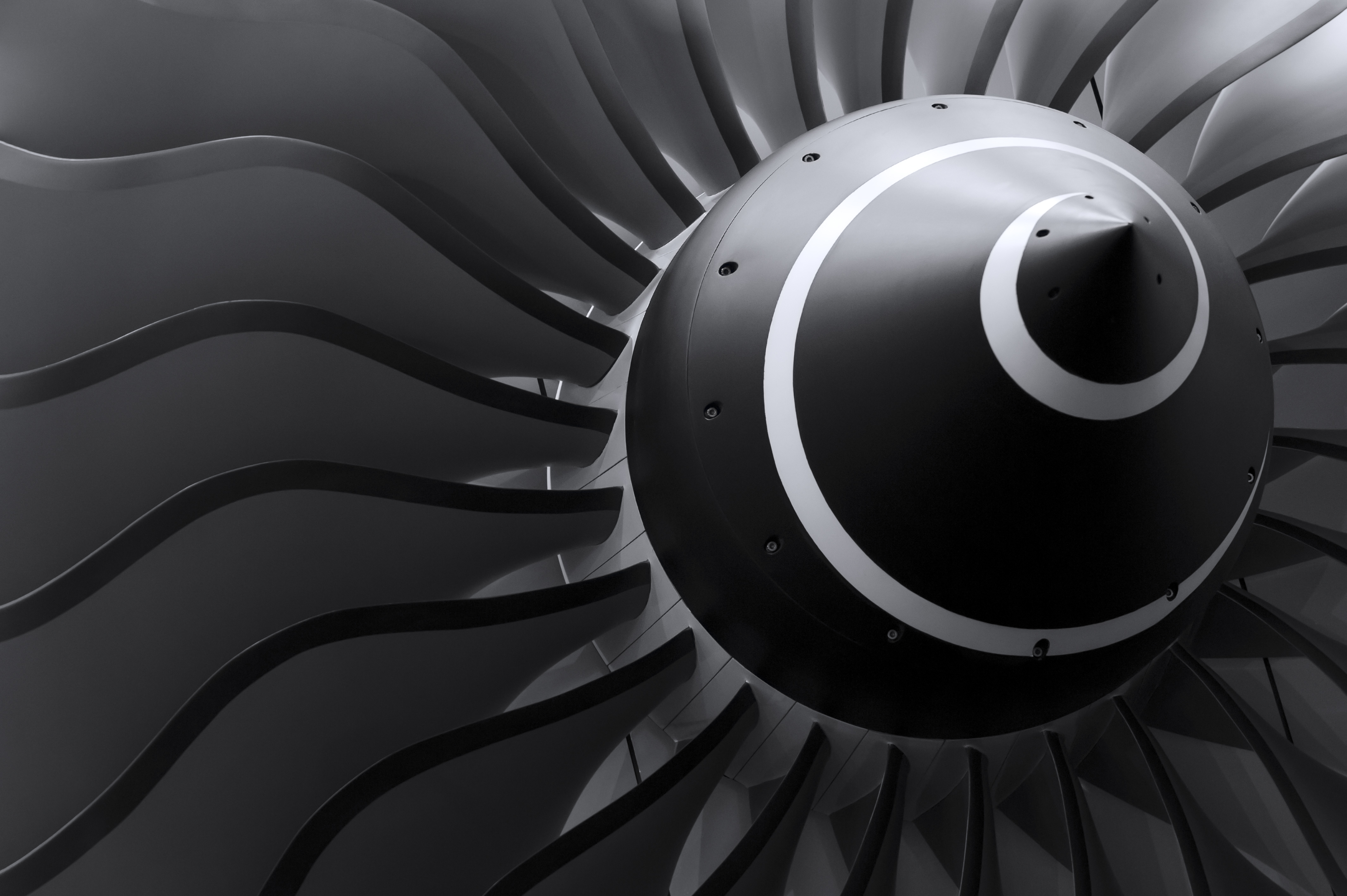

Aeroplanes still rely on fossil fuels to provide the huge amount of power needed for take-off. Globally flights produced

Aeroplanes still rely on fossil fuels to provide the huge amount of power needed for take-off. Globally flights produced