Shipping is widely considered the most efficient form of cargo transport. As a result, it’s the transportation of choice for around 90% of world trade. But even as the most efficient, it still accounts for roughly 3% of global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions.

This may not sound like much, but it amounts to 1 billion tonnes of CO2 and other greenhouse gases per year – more than the UK’s total emissions output. In fact, if shipping were a country, it would be the sixth largest producer of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. And unless there are drastic changes, emissions related to shipping could increase from between 50% and 250% by 2050.

As well as emitting GHGs that directly contribute towards the climate emergency, big ships powered by fossil fuels such as bunker fuel (also known as heavy fuel oil) release other emissions. These include two that can have indirect impacts – sulphur dioxide (SO2) and nitrogen oxides (NOx). Both impact air quality and can have human health and environmental impacts.

As a result, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) is introducing measures that will actively look to force shipping companies to reduce their emissions. In January 2020 it will bring in new rules that dictate all vessels will need to use fuels with a sulphur content of below 0.5%.

One approach ship owners are taking to meet these targets is to fit ‘scrubbers’– devices which wash exhausts with seawater, turning the sulphur oxides emitted from burning fossil fuel oils into harmless calcium sulphate. But these will only tackle the sulphur problem, and still mean that ships emit CO2.

Another approach is switching to cleaner energy alternatives such as biofuels, batteries or even sails, but the most promising of these based on existing technology is liquefied natural gas, or LNG.

What is LNG?

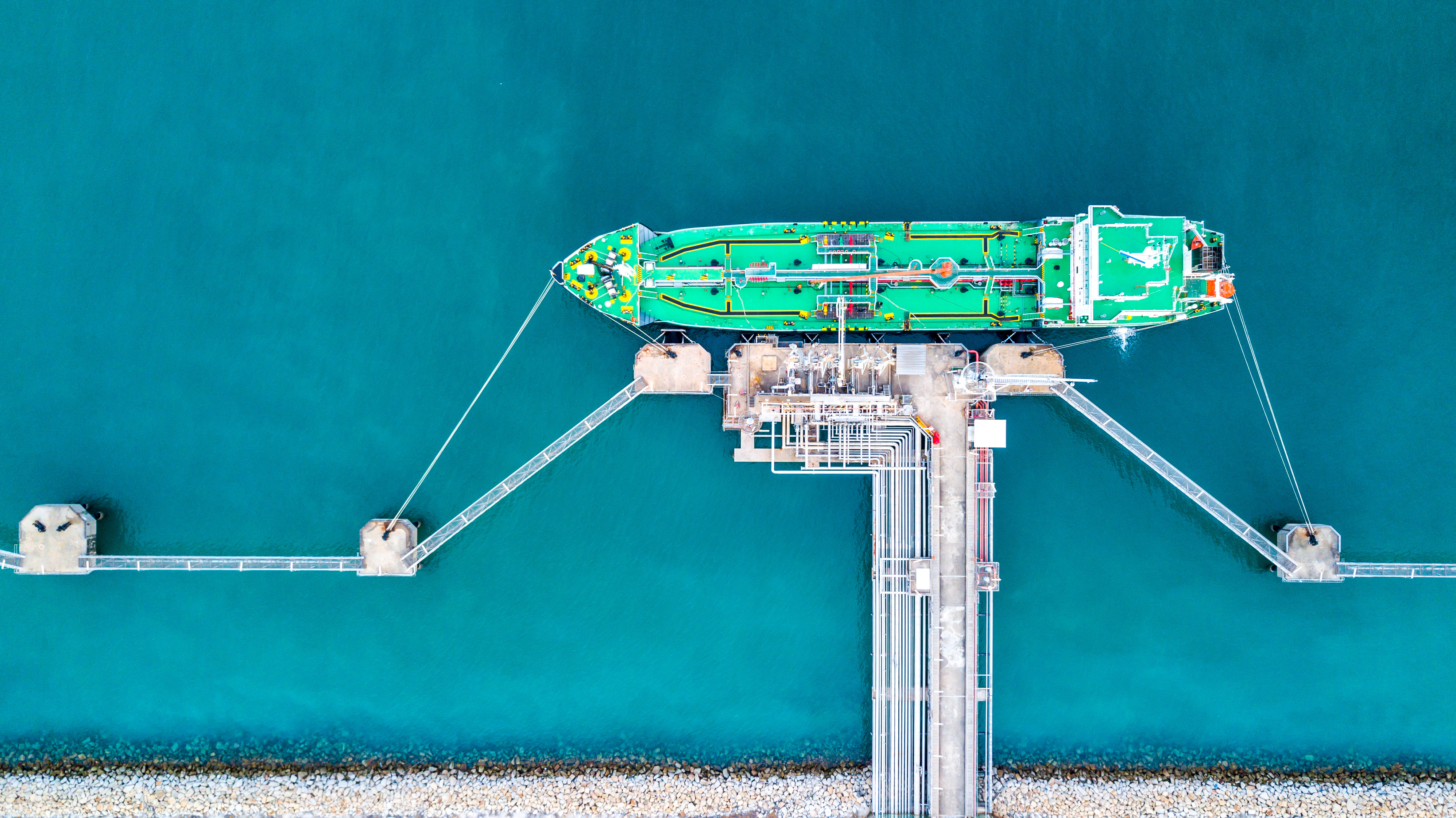

In its liquid form, natural gas can be used as a fuel to power ships, replacing heavy fuel oil, which is more typically used, emissions-heavy and cheaper. But first it needs to be turned into a liquid.

To do this, raw natural gas is purified to separate out all impurities and liquids. This leaves a mixture of mostly methane and some ethane, which is passed through giant refrigerators that cool it to -162oC, in turn shrinking its volume by 600 times.

The end product is a colourless, transparent, non-toxic liquid that’s much easier to store and transport, and can be used to power specially constructed LNG-ready ships, or by ships retrofitted to run on LNG. As well as being versatile, it has the potential to reduce sulphur oxides and nitrogen oxides by 90 to 95%, while emitting 10 to 20% less CO2 than heavier fuel alternatives.

The cost of operating a vessel on LNG is around half that of ultra-low sulphur marine diesel (an alternative fuel option for ships aiming to lower their sulphur output), and it’s also future-proofed in a way that other low-sulphur options are not. As emissions standards become stricter in the coming years, vessels using natural gas would still fall below any threshold.

The industry is starting to take notice. Last year 78 vessels were fitted to run on LNG, the highest annual number to date.

One company that has already embraced the switch to LNG is Estonia’s Graanul Invest. Europe’s largest wood pellet producer and a supplier to Drax Power Station, Graanul is preparing to introduce custom-built vessels that run on LNG by 2020.

The new ships will have the capacity to transport around 9,000 tonnes of compressed wood pellets and Graanul estimates that switching to LNG has the potential to lower its CO2 emissions by 25%, to cut NOx emissions by 85%, and to almost completely eliminate SO2 and particulate matter pollution.

Is LNG shipping’s only viable option?

LNG might be leading the charge towards cleaner shipping, but it’s not the only solution on the table. Another potential is using advanced sail technology to harness wind, which helps power large cargo ships. More than just an innovative way to upscale a centuries-old method of navigating the seas, it is one that could potentially be retrofitted to cargo ships and significantly reduce emissions.

Drax is currently taking part in a study with the Smart Green Shipping Alliance, Danish dry bulk cargo transporter Ultrabulk and Humphreys Yacht Design, to assess the possibility of retrofitting innovative sail technology onto one of its ships for importing biomass.

- What a Pamamax ship carrying wood pellets may look like when retrofitted with sails

- Artist’s impression of a possible design for a wood pellet carrying sailing ship

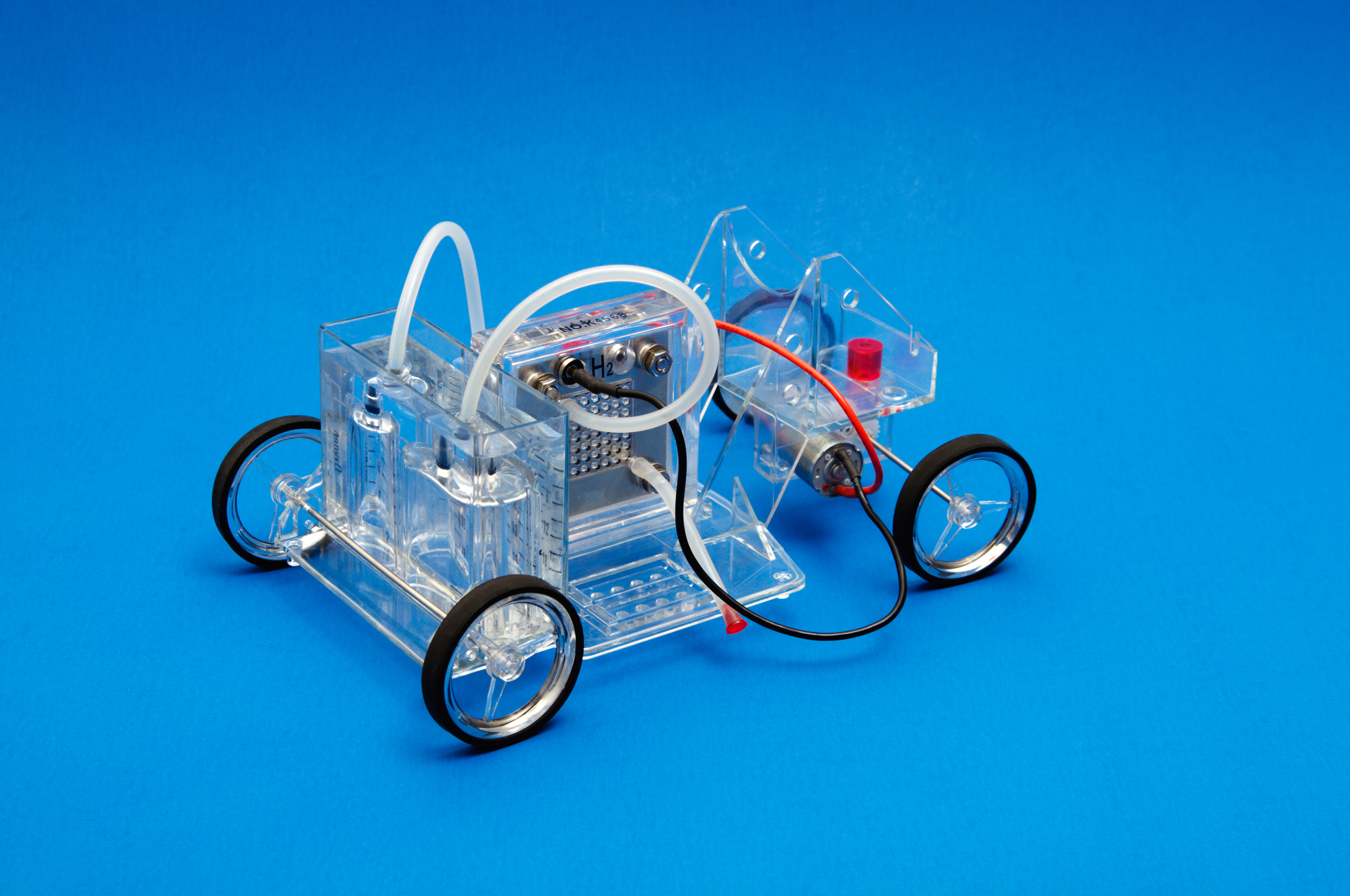

Manufacturers are also looking at battery power as a route to lowering emissions. Last year, boats using battery-fitted technology similar to that used by plug-in cars were developed for use in Norway, Belgium and the Netherlands, while Dutch company Port-Liner are currently building two giant all-electric barges – dubbed ‘Tesla ships’ – that will be powered by battery packs and can carry up to 280 containers.

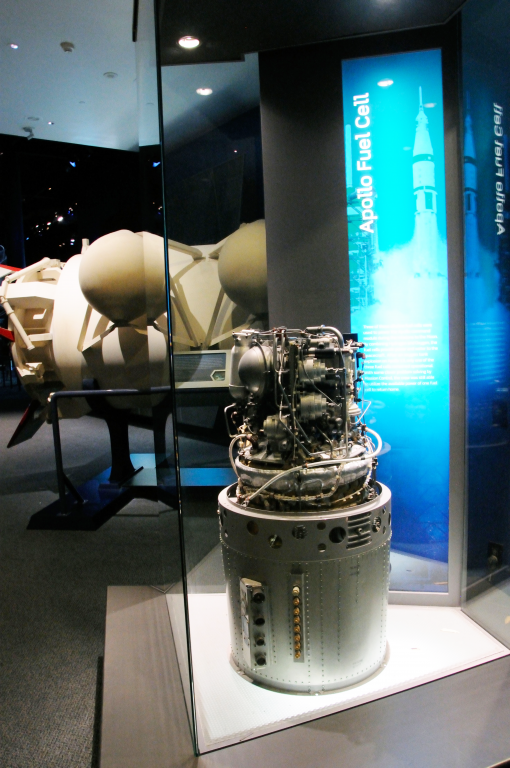

Then there are projects exploring the use of ammonia (which can be produced from air and water using renewable electricity), and hydrogen fuel cell technology. In short, there are many options on the table, but few that can be implemented quickly, and at scale – two things which are needed by the industry. Judged by these criteria, LNG remains the frontrunner.

There are currently just 125 ships worldwide using LNG, but these numbers are expected to increase by between 400 and 600 by 2020. Given that the world fleet boasts more than 60,000 commercial ships, this remains a drop in the ocean, but with the right support it could be the start of a large scale move towards cleaner waterways.

Wood construction fell out of favour in the 19th century when materials like steel and concrete, became more readily available. But new developments in timber manufacturing are changing this.

Wood construction fell out of favour in the 19th century when materials like steel and concrete, became more readily available. But new developments in timber manufacturing are changing this.