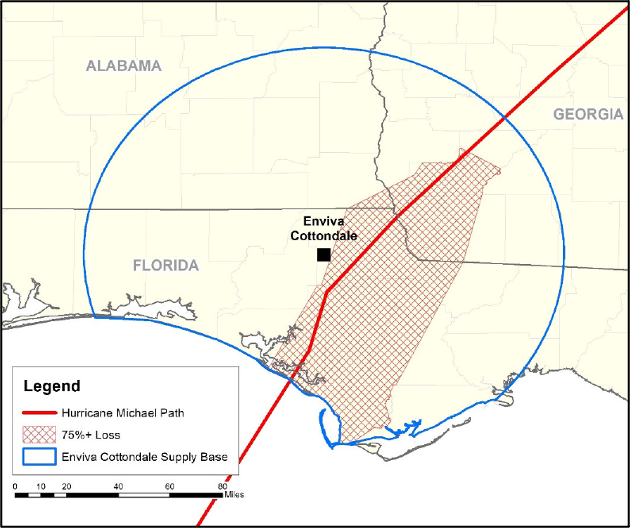

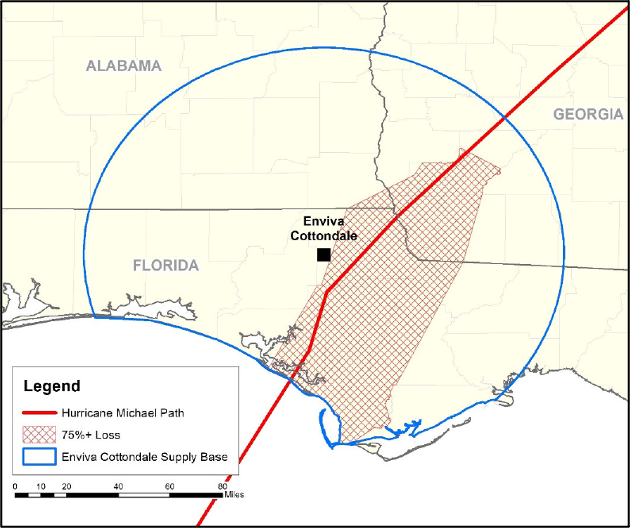

The Enviva Cottondale pellet mill has a production capacity of 760,000 metric tonnes of wood pellets annually. Raw material used by the mill includes a combination of roundwood, chips, and secondary residuals (i.e., sawdust and shavings), with pine accounting for 80‐90% of total feedstock. In October 2018, Hurricane Michael passed through the centre of the Cottondale catchment area, causing significant damage to the forest resource with more than 500,000 hectares (ha) of forestland destroyed and an estimated loss of 42 million m3of timber (equivalent to around 4 times the UK annual production of roundwood).

This event has had an impact on the data trends for forest inventory, growth and harvesting removals – as harvesting levels were increased to salvage as much timber as possible before it became unusable due to decay. This can be clearly seen in many of the charts below. However, these forest areas have been restored and now continue to grow, allowing the catchment area to return to its pre-hurricane trends in the medium term.

Forest Area

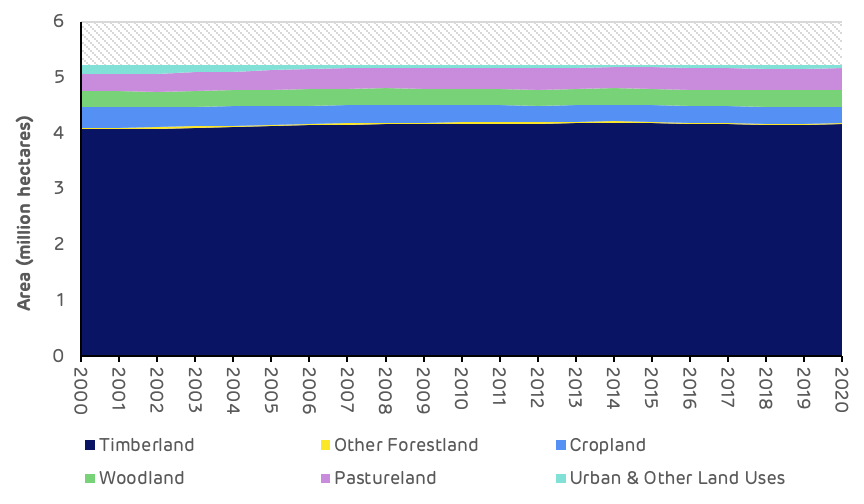

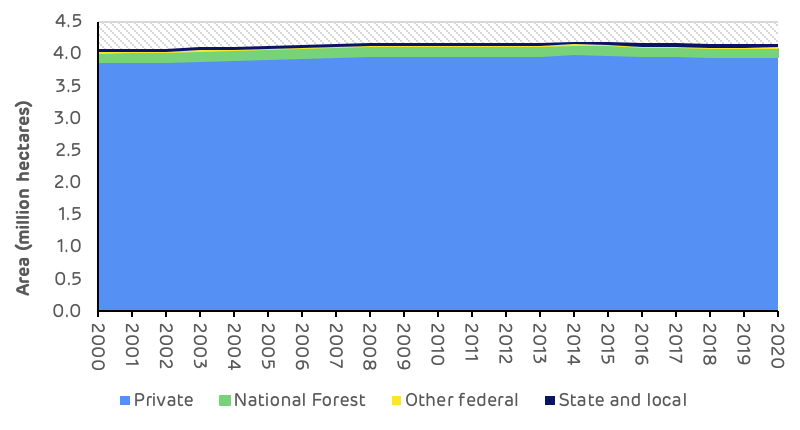

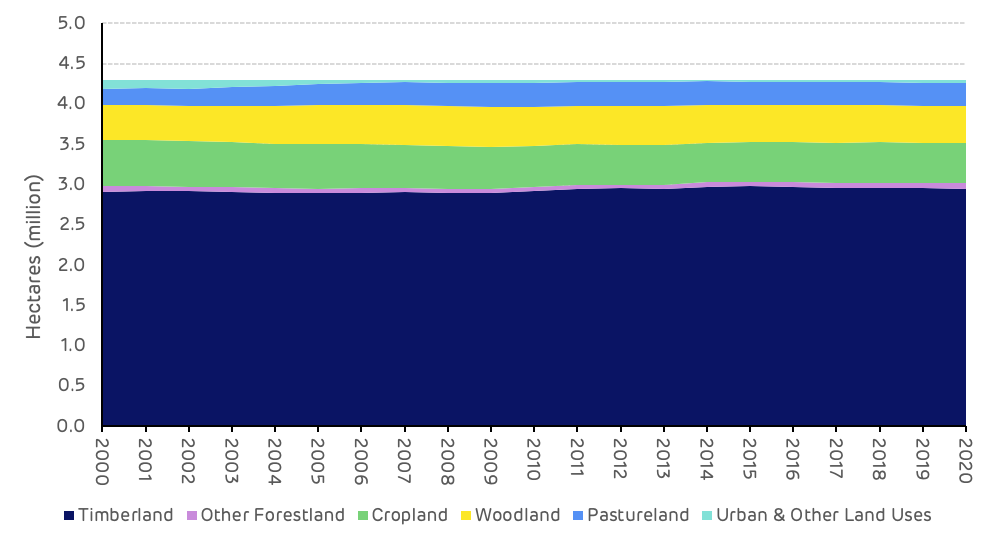

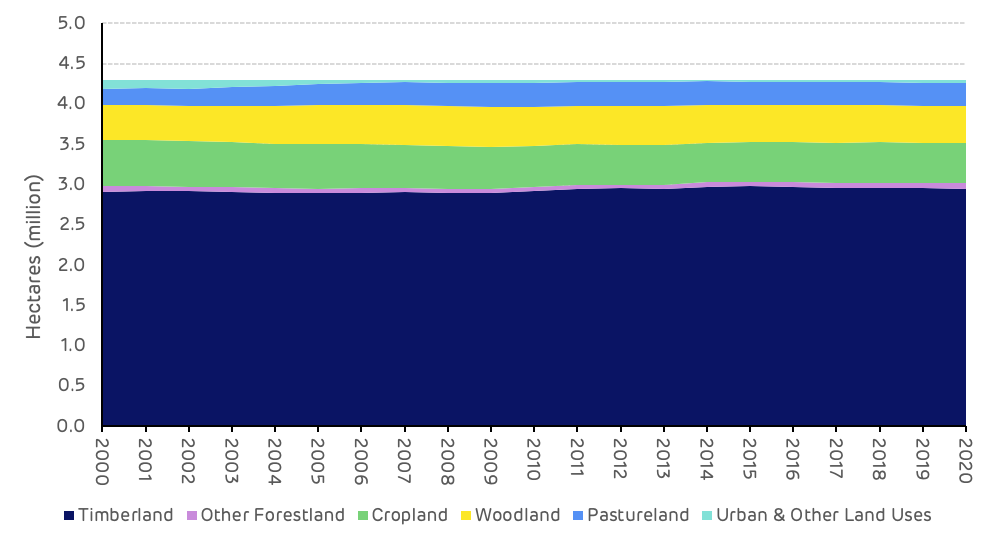

The catchment area around Enviva’s Cottondale pellet mill includes 4.3 million ha of land, based on the historical feedstock sourcing patterns of the mill. Timberland represents 68.7% (2.95 million ha) of the total land area in the Cottondale catchment area, this has increased slightly since 2000 from 67.8% and can be considered to have remained stable over this time period. There are also around 300,000 ha of woodland (associated with agricultural land) and around 800,000 ha of cropland and pastureland. Forestry is the dominant land use in this catchment area (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Land area by usage

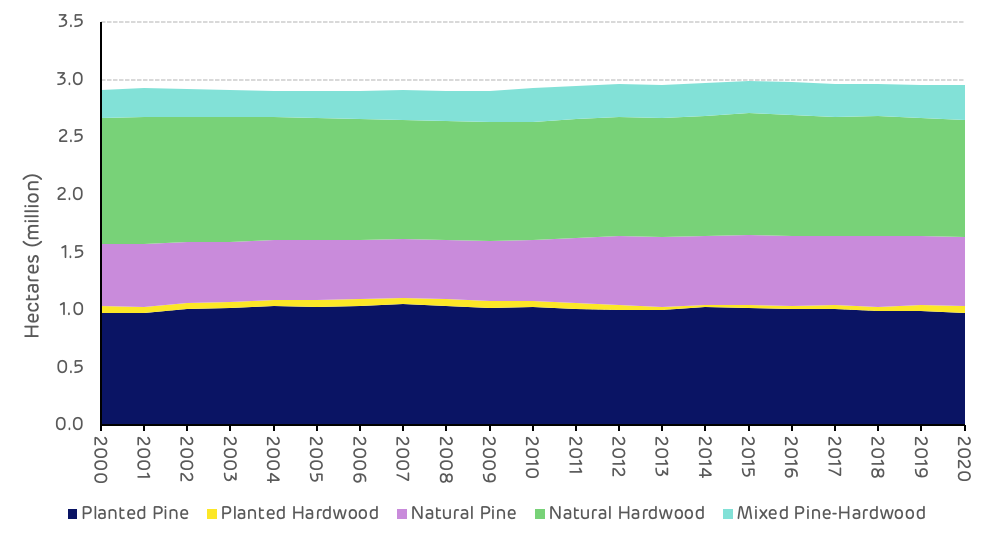

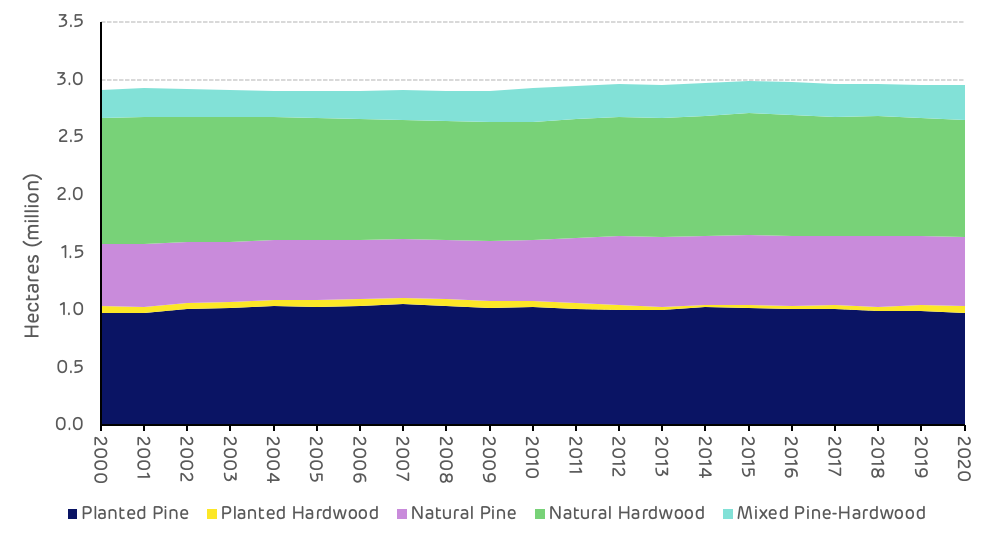

Planted pine represents 33% of the timberland area, natural pine 20%, with 10% mixed stands and the remainder being hardwood forest of which 94% is naturally regenerated (Figure 2). The breakdown of forest type and species composition has remained relatively stable and largely unchanged over the last 20 years, in contrast to other parts of the US South where some natural pine stands have been converted to planted pine. The pine and mixed forest areas are actively managed and produce the majority of the timber harvest in the catchment area. Despite the large area of hardwood forest, management and timber production is limited. Much of this area is classified as bottomland hardwood located alongside rivers, streams, and creeks and in streamside management zones (SMZs), which restricts active management. In addition, the proportion of this catchment area located in Florida contains a large area of swampland, which is largely composed of hardwoods and cannot be actively managed for timber production and is recognised as having important ecological value.

Figure 2: Breakdown of forest type

Volume and Growth

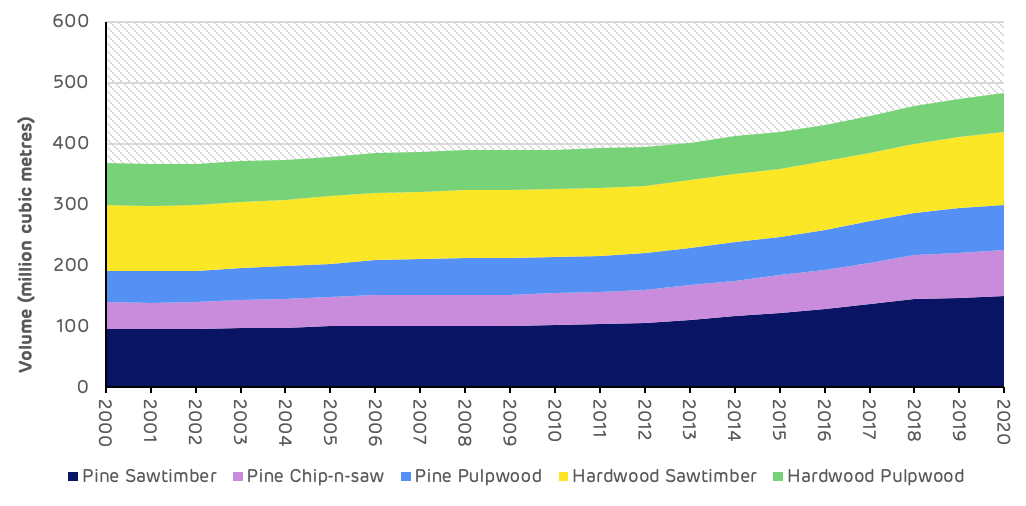

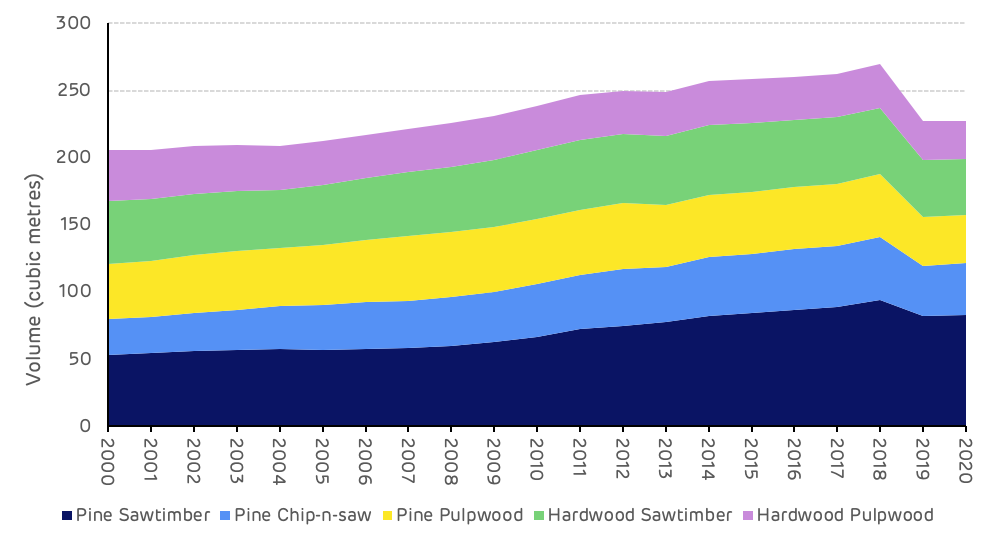

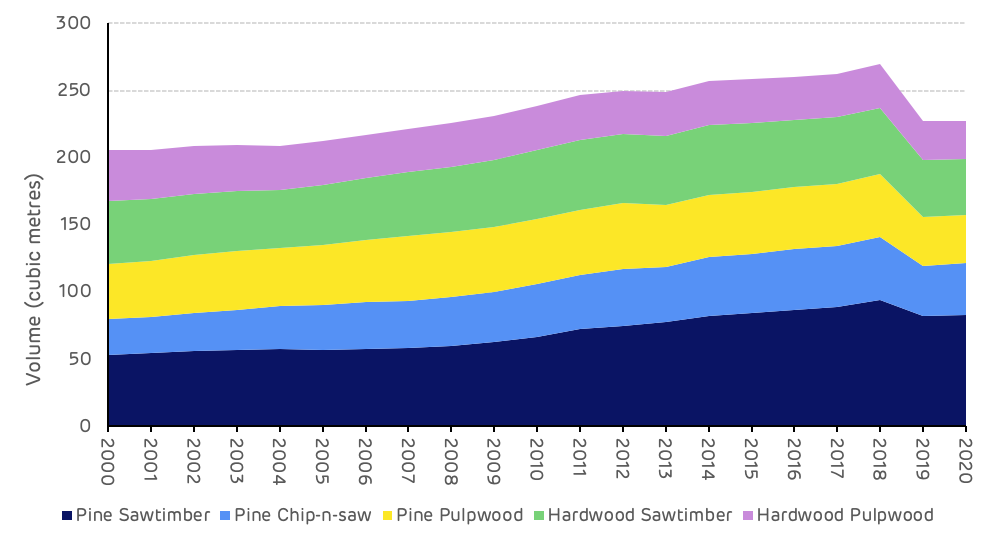

The overall trend of volume and growth in the Cottondale catchment area is of a maturing forest resource and an increasing accumulation of standing volume, particularly in the larger forest product classes (saw-timber and chip-n-saw). Figure 3 shows that total standing volume increased by 64 million m3 from 2000 to 2018, with the largest increases in the pine saw-timber and chip-n-saw categories. In 2018, the devastating impact of Hurricane Michael caused a substantial reduction in the standing volume across every product category with the total standing volume being reduced by 42 million m3. This event has had a significant impact on the forest resource and is a primary cause of recent data trends.

However, the overall long-term trend in the catchment area is of maturing forest and increasing inventory. This should continue in the long-term once the impact of the hurricane damage has been managed and replacement forest areas begin to mature.

Figure 3: Standing volume by product category

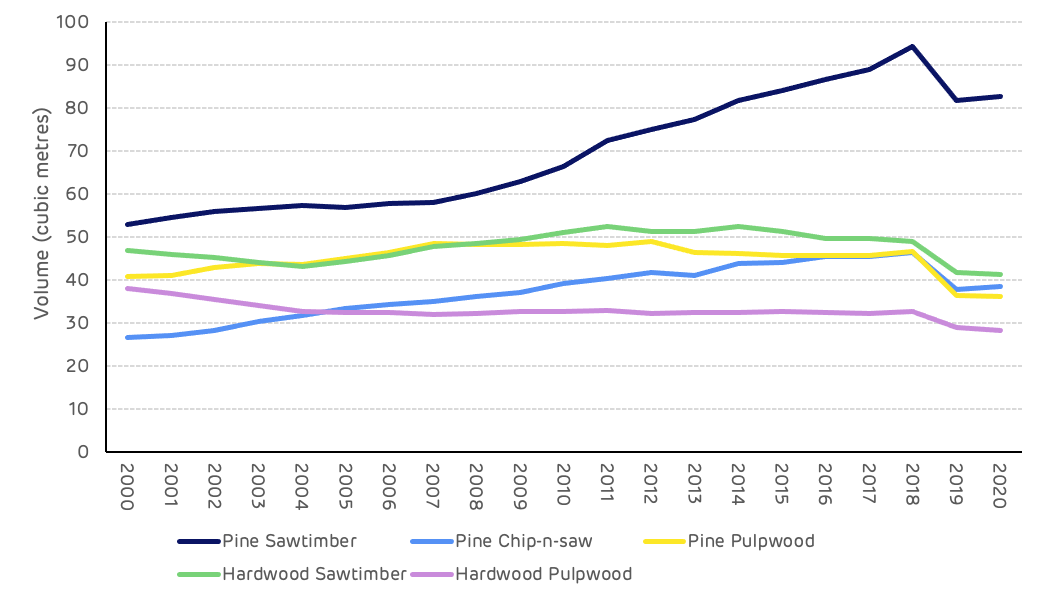

Pine pulpwood inventory increased steadily by around 8 million m3 from 2000 to 2013, reaching a peak of 49 million m3. This then declined slightly to 46 million m3 in 2018 due to the maturing age class of the forest and pulpwood forest growing into the larger size class of chip-n-saw and saw-timber forest (Figure 4), in addition to an increase in pulpwood demand as biomass markets became operational and ramped up production. Following the hurricane in 2018, the pine pulpwood inventory dropped by more than 10 million m3.

Replanting and reforestation of damaged areas will ensure that future pine pulpwood production will increase again once these forests start to mature.

In the period from 2000 to 2018 pine sawtimber standing volume increased by 41.5 million m3 (78%) and chip-n-saw by 19.6 million m3 (73%), indicating a maturing age class and a growing forest resource. The 2018 hurricane caused a reduction in standing volume in both of these product categories of 11.6 and 8 million m3respectively (12% and 17% of the 2018 volume). However, the increasing trend is likely to continue once the forest area recovers.

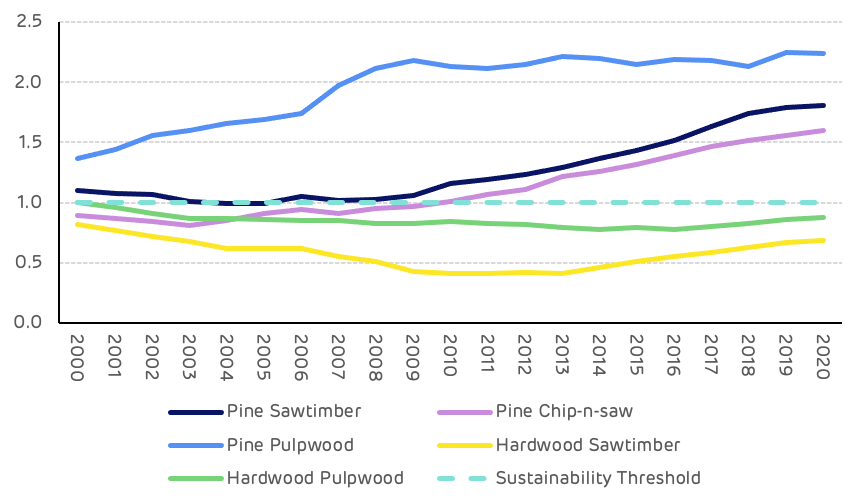

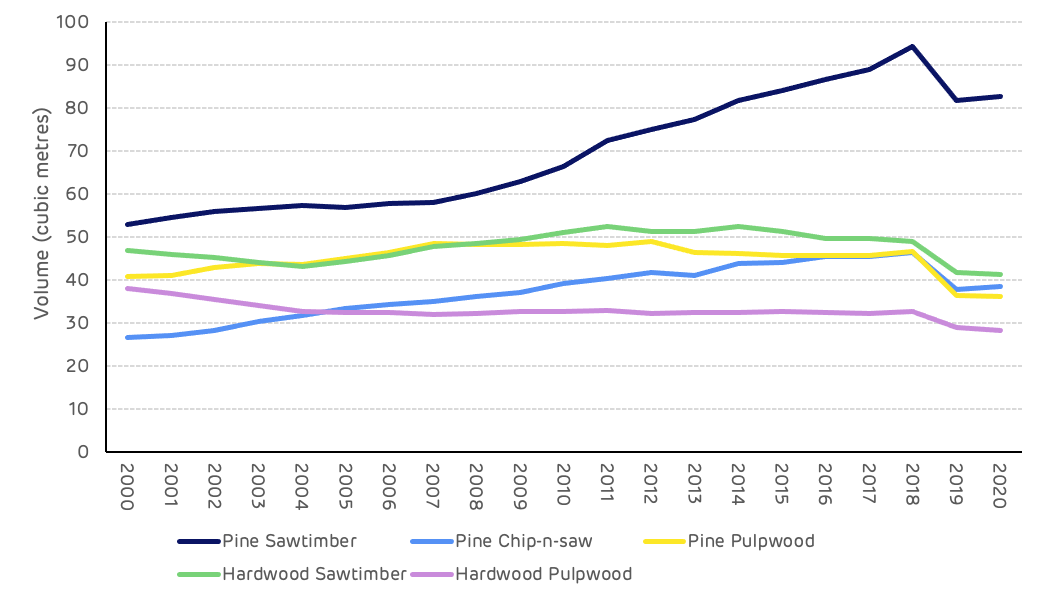

Figure 4: Standing volume by product category

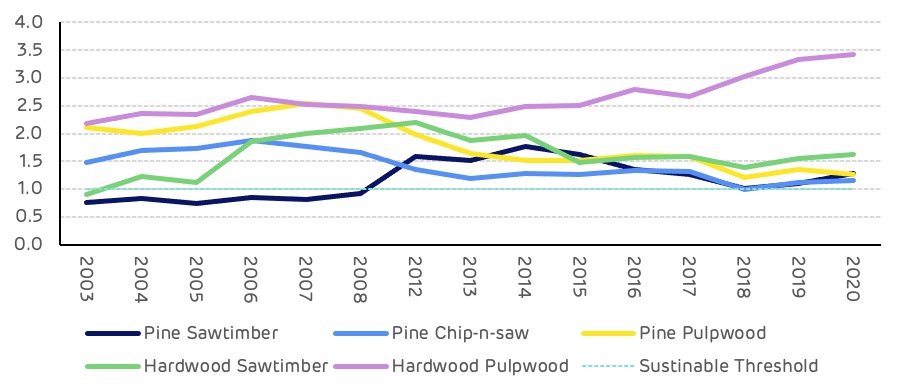

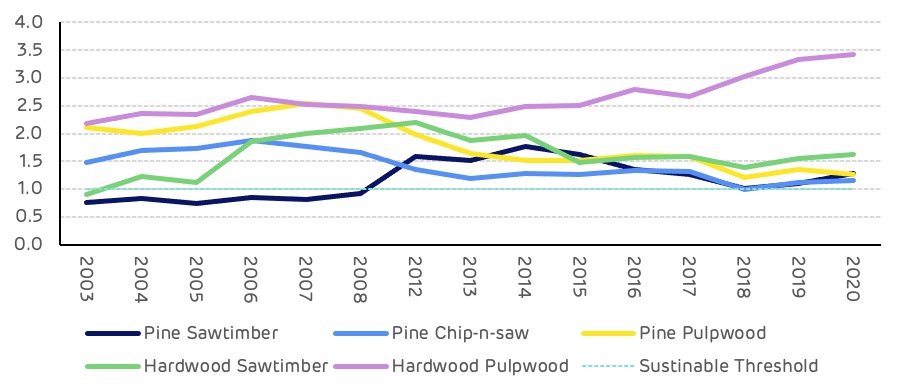

The growth drain ratio (GDR) is the comparison of average annual growth to removals (typically harvesting), where the growth exceeds removals the GDR will be in excess of 1 and this is considered sustainable, where removals exceed growth then the GDR will be less than 1 and this is not sustainable if maintained in the long-term – although in the short-term this can be a factor of large areas of mature forest with low growth rates and high rates of harvesting, short periods of high demand for a particular product or salvage harvesting after a natural disturbance. The GDR should be considered over a longer time period to ensure it reflects the long-term trend. In the period from 2003 to 2020 the combined GDR for pine products averaged 1.52 with a high of 1.84 and a low of 1.08 (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Growth to drain ratio by product category

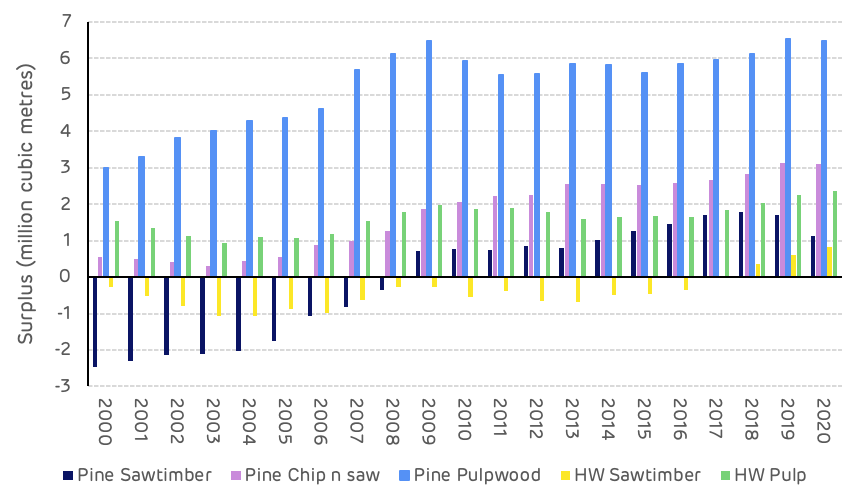

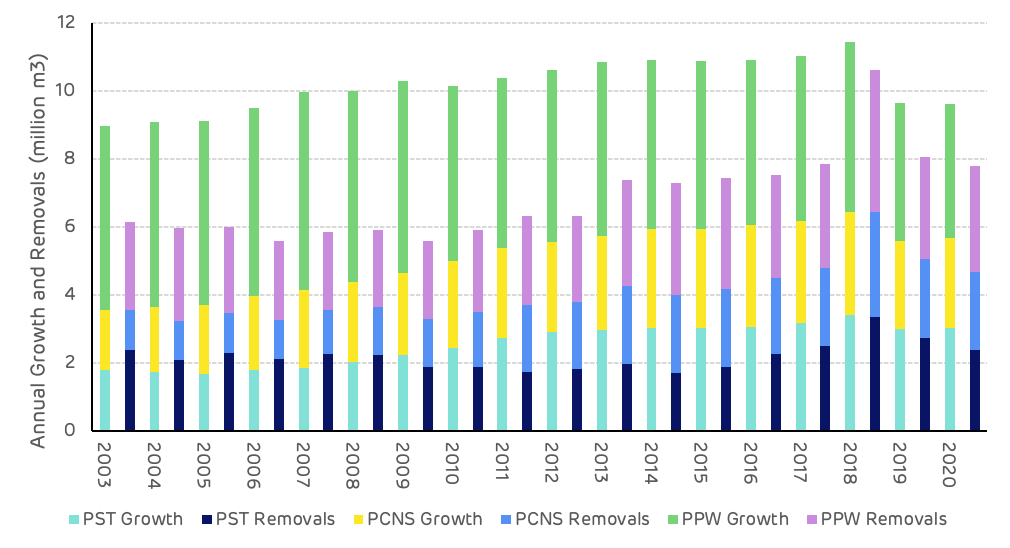

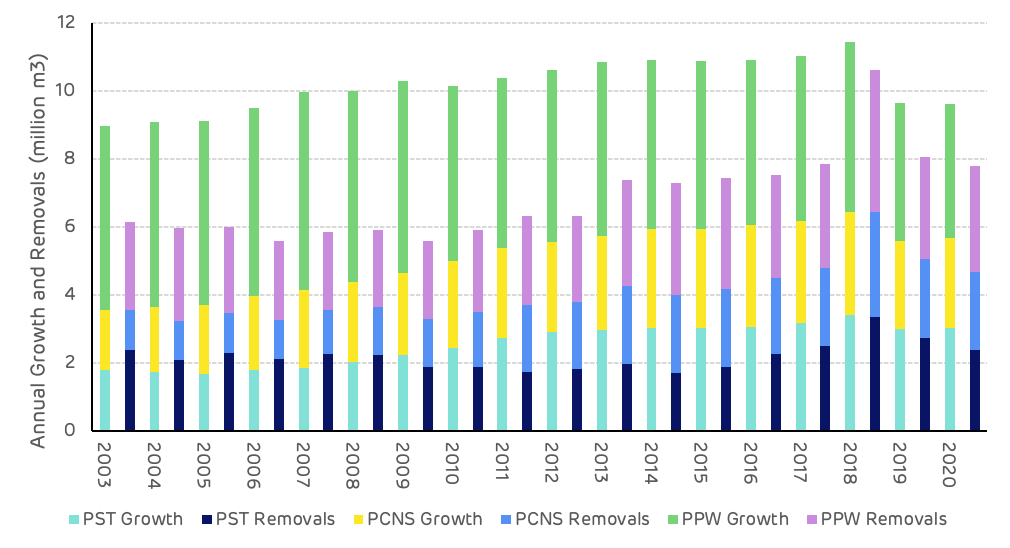

The maturing forest resources can be clearly seen from the growth to removals data for each product category. Average tree sizes getting larger and more pulpwood class stands moving into the larger saw-timber and chip-n-saw categories. This trend can be seen by comparing the data values from 2003 and 2018 where saw-timber average annual growth increased by 90% (1.6 million m3), and removals by 41% (0.98 million m3). Chip-n-saw growth increased by 73% (1.3 million m3) whilst removals increased by 160% (1.9 million m3). Pulpwood growth decreased by 7.5% (0.4 million m3) whilst removals increased by 63% (1.6 million m3). Over this time period the total annual surplus of pine growth compared to removals averaged 3.7 million m3 per year (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Pine growth and removals by product category and year

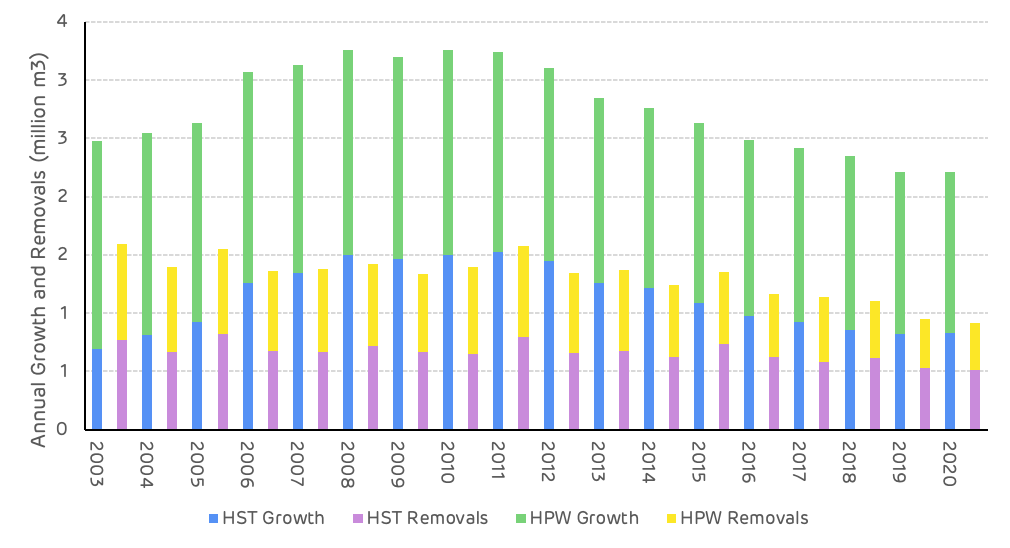

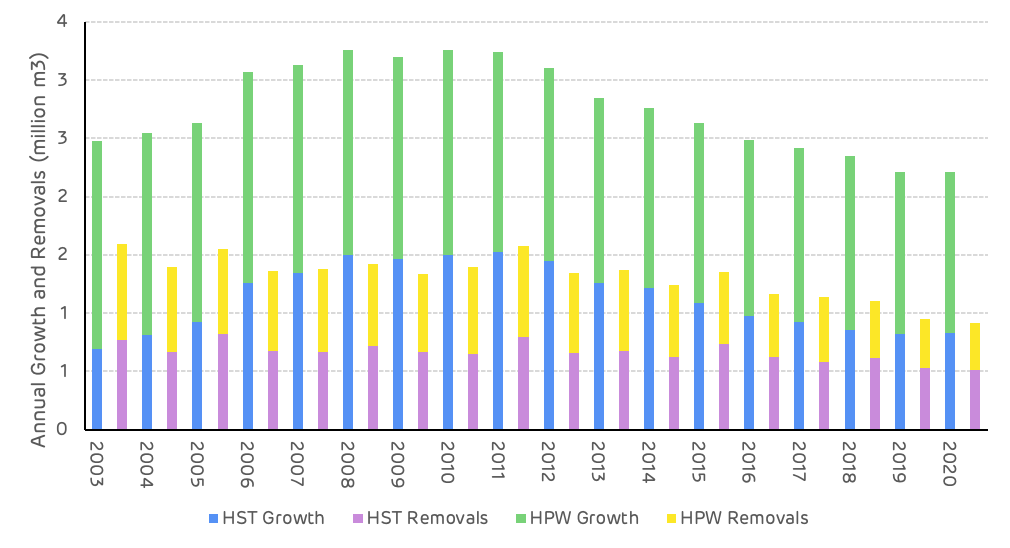

Hardwood saw-timber and pulpwood removals declined by 20% and 40% respectively between 2000 and 2018, whilst growth increased by 23% for hardwood saw-timber and declined by 16% for hardwood pulpwood. The average annual hardwood surplus over this time period was 1.5 million m3 per year (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Hardwood growth and removals by product category and year

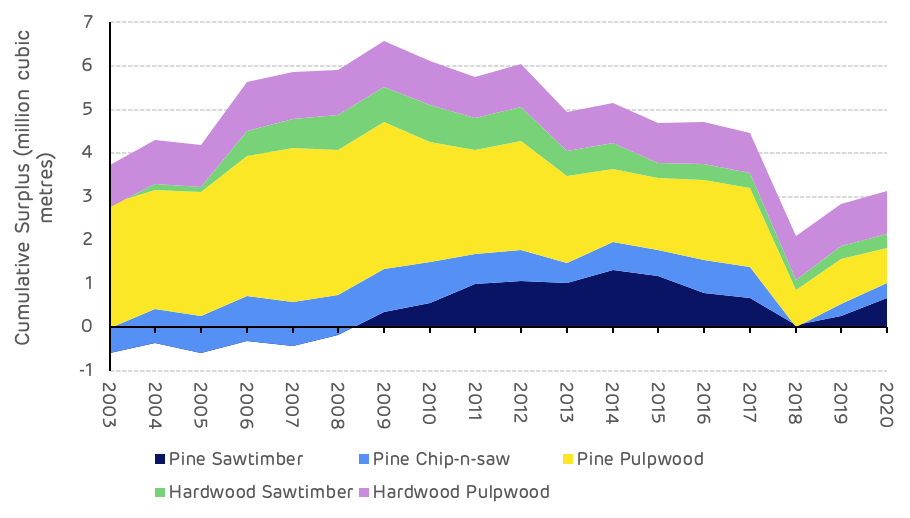

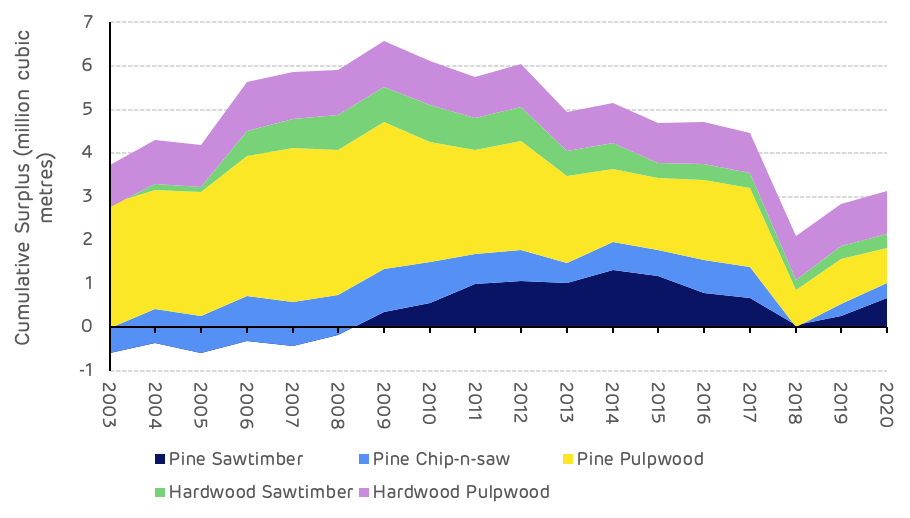

Despite a short-term imbalance in some product categories, the overall surplus of pine growth compared to removals has remained strong, with an average of 3.3 million m3 between 2000 and 2020, which includes the increased salvage harvesting in 2018 (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Cumulative annual surplus of growth compared to removals

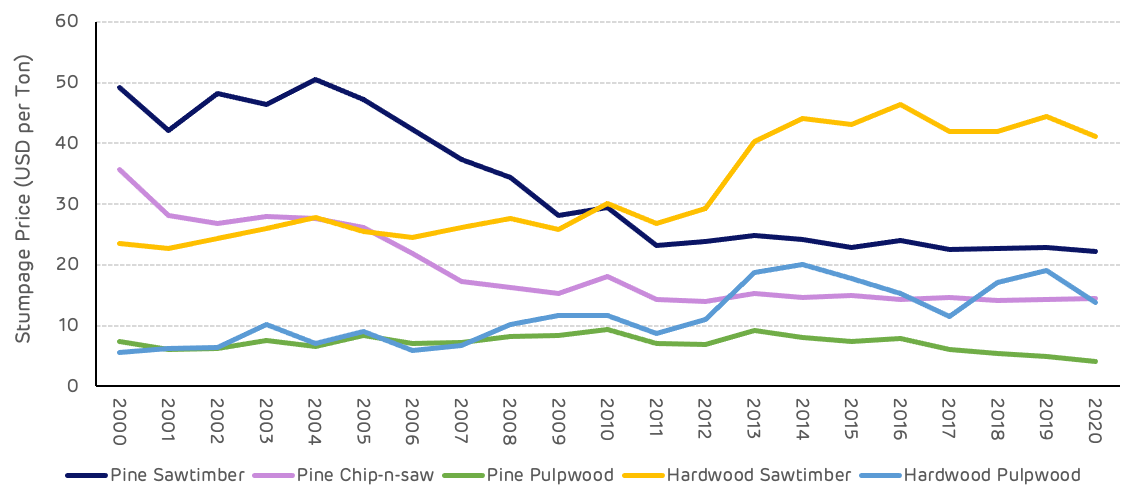

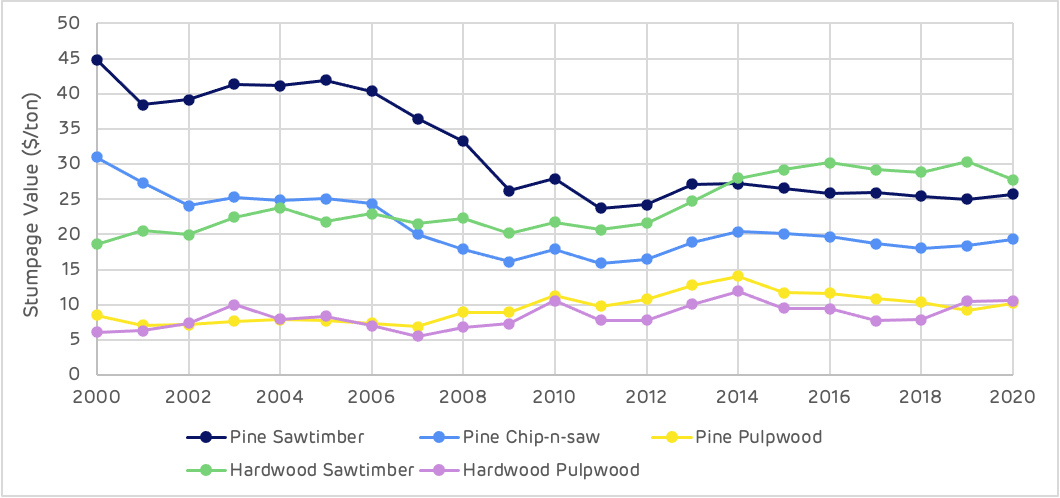

Wood Prices

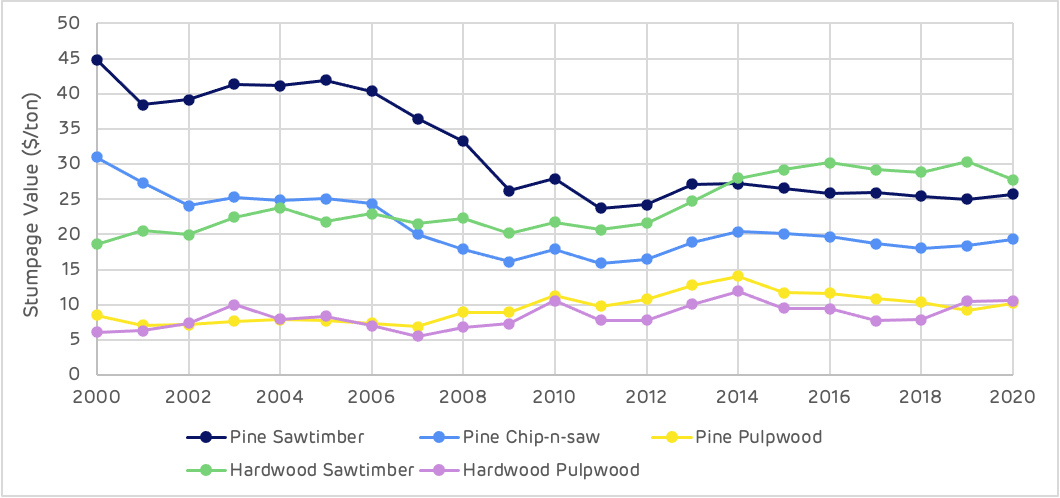

Stumpage price is the value paid to the forest owner for each category of product at the time of harvesting. The variation in prices in the Cottondale catchment area has been significant and shows some interesting trends. The higher value pine products (saw-timber and chip-n-saw) began with high stumpage values in 2000, as markets were strong for construction and furniture grade timber and supply limited at that stage due to the young age class and predominance of pulpwood stands at that time. In 2008, following the global economic crisis and the crash in housing and construction markets, saw-timber prices declined substantially reaching a low of $23 per ton, a 47% decline from the 2000 price. This stumpage price has never recovered, despite an improvement in the economy and an increase in housing starts and demand for structural timber. The reason for the continued deflated saw-timber stumpage price is a substantial surplus of supply in this catchment area. As the forest area has matured and more saw-timber grade stands are available, markets have been able to satisfy demand without an increase in price.

Pine pulpwood prices at Cottondale were lower than the US South-wide average in 2000 and remained relatively low until around 2013. A reduction in saw-timber production, and consequent reduction in mill residuals, due to the recession of 2008, led to a shortage of pulp mill feedstock and increased harvesting of pulpwood stands. This caused an increase in pine pulpwood stumpage values alongside an overall increase in demand as biomass and pellet markets began production around this time. The data shows a short-term spike in pine pulpwood stumpage prices in 2013-14, but this returned to a more normal trend as more saw-timber residues became available and pulpwood stumpage values have been around $10-11 per ton since 2015 (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Variation in stumpage value over time

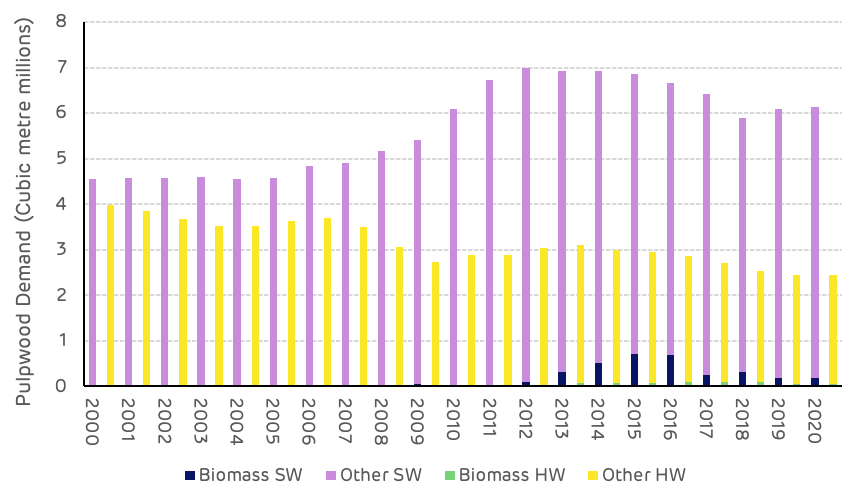

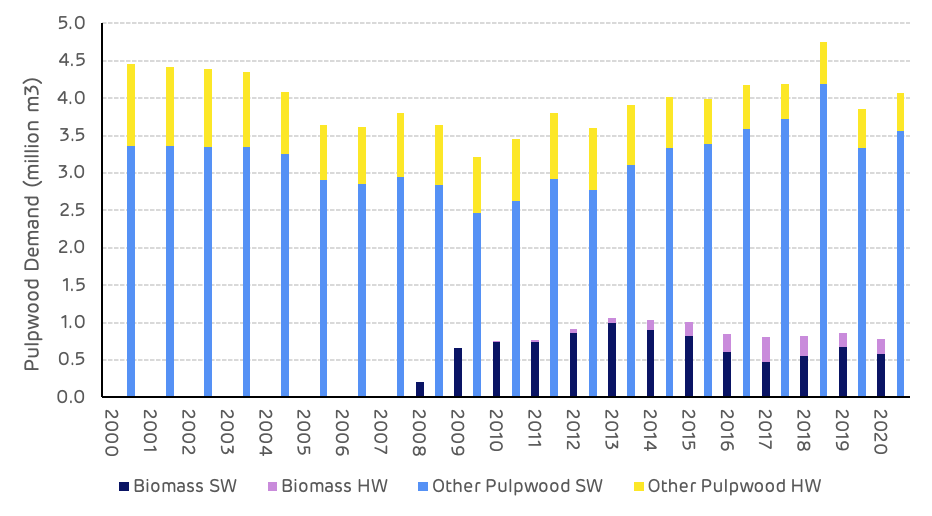

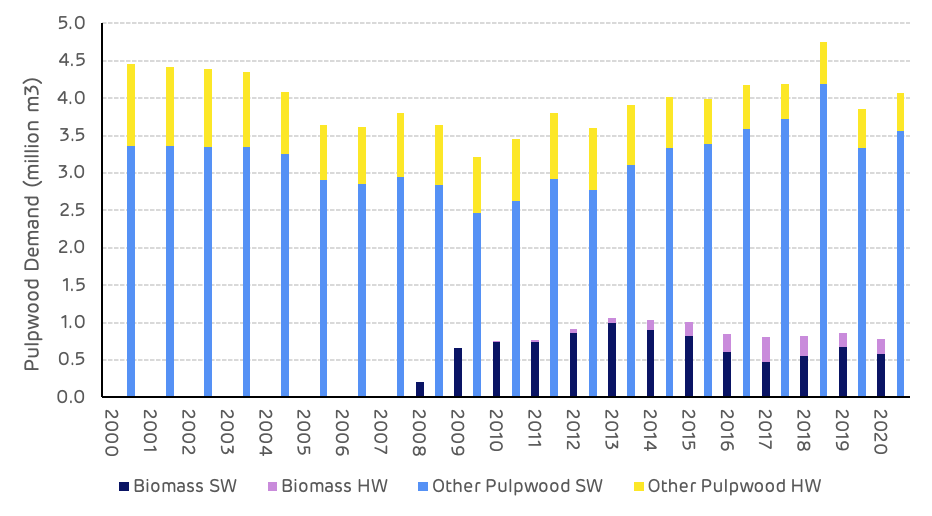

Biomass demand

Biomass demand in the Cottondale catchment area began in 2008 and has averaged around 800 thousand m3per year since that time with a high of just over 1 million m3 in 2013 to 2015 and a low of 200 thousand m3 in 2008. Other pulpwood markets have had an average annual demand of 3.97 million m3 between 2000 and 2020 with a high of 4.76 million m3 in 2018 and a low of 3.2 million m3 in 2009. In 2020 the biomass market represented 16% of the total pulpwood demand in the Cottondale catchment area (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Total pulpwood demand

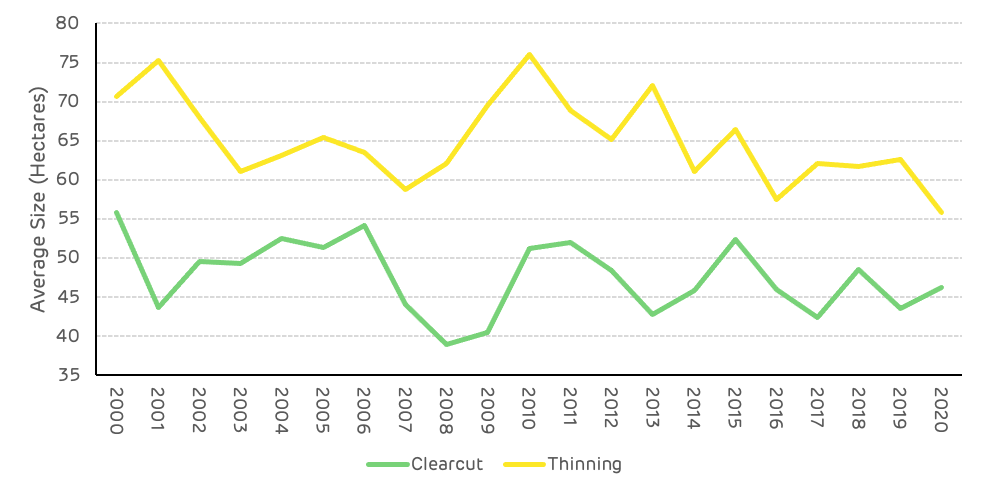

Forest Management

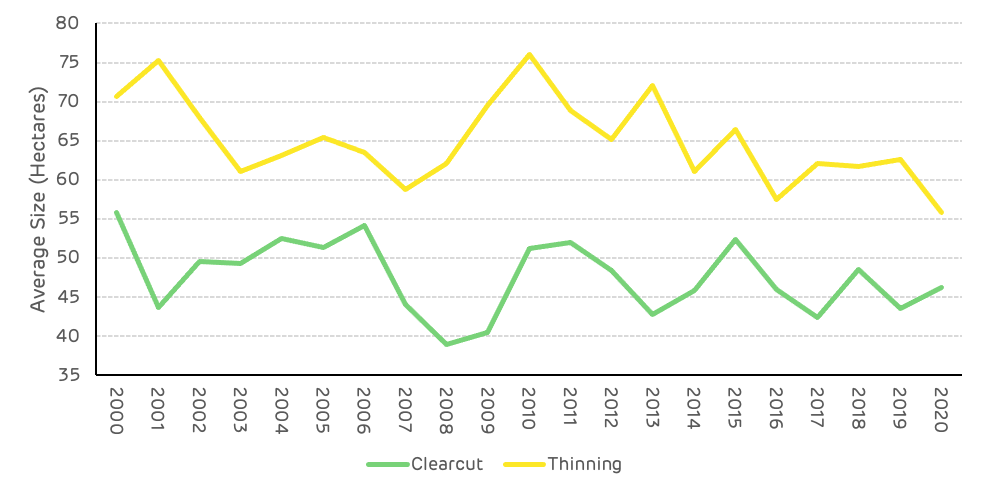

The average size of clear-cut harvesting sites from 2000 to 2020 has been 47 ha, ranging from 38 ha up to 56 ha. The average size of thinning sites has been 65 ha, ranging from 55 ha up to 76 ha. When isolating the period from 2000 to 2010 and 2011 to 2020, the averages and range remain very similar, suggesting that there has been no significant change in harvesting coupe size over this period.

Figure 11: Average size of harvesting sites

The impact of biomass and wood pellet demand on the key metrics in this catchment area are considered below. This is a summary of Hood Consulting’s view on the trends and impacts in the Cottondale catchment area.

Is there any evidence that bioenergy demand has caused the following:

Deforestation?

No. US Forest Service (USFS) data shows a 55,166-hectare (+1.9%) increase in the total area of timberland in the Enviva Cottondale catchment area since the Enviva Cottondale pellet mill commenced production in 2008. Furthermore, a strong positive relationship was identified between biomass demand and timberland area, suggesting that the increase in timberland area since 2008 can be linked, to a degree, to increased demand attributed to bioenergy.

A change in management practices (rotation lengths, thinnings, conversion from hardwood to pine)?

Inconclusive. Changes in management practices have occurred in the catchment area over the last two decades. However, the evidence is inconclusive as to whether increased demand attributed to bioenergy has caused or is responsible for these changes.

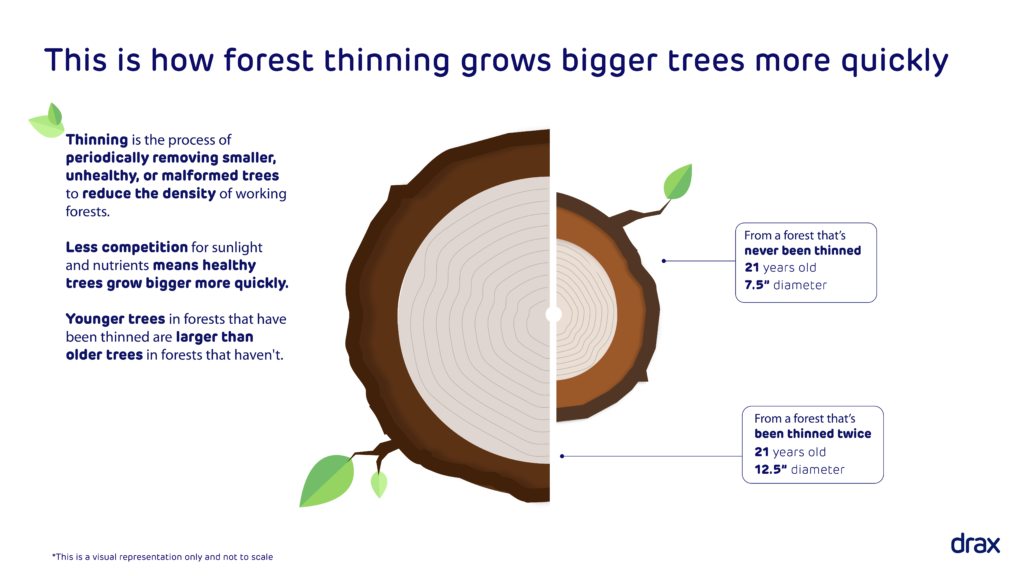

Clearcuts and thinnings are the two major types of harvests that occur in this region, both of which are long-standing, widely used methods of harvesting timber. TimberMart-South (TMS) data shows that thinnings accounted for 63% of total reported harvest area in the Cottondale market from 2005-2011 but only 39% of total harvest area reported from 2012-2020. Specifically, the decreased prevalence of thinning since 2012 can be linked to the strengthening of pine pulpwood markets and concurrent weakening of pine sawtimber markets beginning in the mid-2000s.

Prior to the bursting of the US housing bubble in 2006, timber management in this market had been driven to a large degree by pine sawtimber production. However, challenging market conditions saw pine sawtimber stumpages prices decline more than 40% from 2006-2011. At the same time, pine pulpwood markets started to strengthen, with pine pulpwood stumpage prices increasing more than 50% from 2006-2010. So, with sawtimber markets weakening and pulpwood markets strengthening, the data suggests that many landowners decided to alter their management approach (i.e. to take advantage of strong pulpwood markets) and focus on short pulpwood rotations that typically do not utilize thinnings.

Bioenergy has had an impact on this market by adding an average of roughly 680,000 metric tons of additional pine pulpwood demand to this catchment area annually since 2008. However, bioenergy has accounted for only 17% of total softwood pulpwood demand in this market since Enviva Cottondale’s startup. Ultimately, the shift in management approach that occurred in this market can be more closely linked to other factors, such as increased softwood pulpwood demand from non-bioenergy sources (i.e. pulp/paper) as well as the weakening of pine sawtimber markets.

Diversion from other markets?

No. Demand for softwood (pine) sawlogs increased an estimated 23% in the Cottondale catchment area from 2008-2020. Also, there is no evidence that increased demand from bioenergy has caused a diversion from other softwood pulpwood markets (i.e. pulp/paper), as softwood pulpwood demand not attributed to bioenergy has increased 25% since the Cottondale mill’s startup in 2008.

An unexpected or abnormal increase in wood prices?

Inconclusive. The startup of Enviva Cottondale added more than 900,000 metric tons of softwood pulpwood demand to the catchment area from 2008-2013, and this increase in demand coincided with a 28% increase in the delivered price of pine pulpwood (PPW) – the primary roundwood product consumed by the Enviva Cottondale mill. However, since 2013, delivered PPW prices have held flat, despite biomass-related softwood pulpwood demand falling to an average of roughly 635,000 tons per year since 2016, down more than 40% compared to 2013 peak levels. (Note the decrease in roundwood consumption was due to a higher utilization of secondary residuals). It’s also important to point out that the roughly 410,000-metric ton decrease in softwood biomass demand from 2013 to 2020 was offset by a roughly 455,000-metric ton increase in softwood pulpwood demand from other sources.

Statistical analysis did identify a positive relationship between softwood biomass demand and delivered PPW price. However, that relationship was found to be relatively weak. The relationship between delivered PPW price and softwood pulpwood demand from other sources was found to be much stronger, which was not unexpected to find given that softwood pulpwood demand not attributed to bioenergy has accounted for 83% of total softwood pulpwood demand in the catchment area since 2008.

Furthermore, there is some evidence linking the increase in pine sawmill chip prices to increased consumption of secondary pine residuals by Enviva Cottondale. Specifically, consumption of secondary pine residuals by Enviva Cottondale more than doubled from roughly 213,000 metric tons in 2012 to nearly 490,000 metric tons in 2016, and this increased consumption of pine residuals coincided with a nearly 20% increase in the price of pine sawmill chips. However, increased consumption of residuals by the bioenergy sector was only one of several contributing factors that can be linked to the increase in pine sawmill chip prices. Increased consumption of pine residuals by the pulp/paper industry also contributed to higher pine sawmill chip prices. In addition, there is a strong linkage between pine sawmill chip prices and softwood lumber production. Specifically, the increase in softwood lumber production that begun in the early-to-mid-2010s consequently resulted in the increased production of secondary residuals, and the increased availability of this lower-cost material led to greater competition and ultimately higher pine residual prices.

A reduction in growing stock timber?

No. From 2008 (the year Enviva Cottondale commenced production) up until Hurricane Michael struck in late-2018, total growing stock inventory increased an average of 1.8% per year (+19% total) in the Cottondale catchment area. Specifically, inventories of pine sawtimber and pine chip-n-saw increased 58% and 28%, respectively, while pine pulpwood (PPW) inventory decreased 4% over this same period.

However, note that the decrease in pine pulpwood inventory from 2008-2018 was not due to increased demand from bioenergy or increased harvesting above the sustainable yield capacity of the forest area, as annual growth of pine pulpwood exceeded annual removals every year throughout this period. Rather, this slight decrease in PPW inventory levels is more a reflection of the aging of the catchment area forest and the movement of stands classified as pulpwood to stands classified as chip-n-saw.

A reduction in the sequestration rate of carbon?

No. US Forest Service (USFS) data shows the average annual growth rate of total growing stock timber in the Cottondale catchment area decreased from 5.9% in 2008 to 5.2% in 2020, suggesting that the sequestration rate of carbon also declined slightly over this period. However, there is little evidence to suggest that increased demand attributed to bioenergy is responsible for this change.

The reduction in overall growth rate (and therefore reduction in the sequestration rate of carbon) is more a reflection of the aging of the catchment area forest. Specifically, growth rates decline as timber ages, and this is exactly what USFS data shows in the Cottondale catchment area, with the average age of growing stock timber increasing from less than 44 years of age in 2008 to nearly 46 years of age in 2020.

An increase in harvesting above the sustainable yield capacity of the forest area?

No. Growth-to-removals (G:R) ratios, which compare annual timber growth to annual timber removals, provides a measure of market demand relative to supply as well as a gauge of market sustainability. In 2020, the latest available, the G:R ratio for pine pulpwood (PPW), the predominant timber product utilized by the bioenergy sector, equaled 1.26 (recall that a value greater than 1.0 indicates sustainable harvest levels).

Note, however, that the PPW G:R ratio averaged 1.57 in the catchment area from 2013-2017 before falling to 1.20 in 2018 and averaging 1.27 since. This notable drop in 2018 was due to a nearly 35% increase in PPW removals (due to Hurricane Michael). It’s also important to note that while annual removals have moved back in line with pre-Michael levels since 2019, this lower PPW G:R ratio is likely reflective of the new norm (at least over the midterm). Hurricane Michael destroyed an estimated 22% of total pine pulpwood inventory in the Cottondale catchment area, and this loss in inventory will be reflected in reduced growth until the destroyed forests regenerate. However, in spite of this loss, adequate PPW inventory levels still remain and sustainable market conditions are expected to persist moving forward.

Timber growing stock inventory

Neutral. According to USFS data, inventories of pine pulpwood (PPW) decreased 25% in the catchment area from 2008-2020. However, this substantial decrease was due to Hurricane Michael, which destroyed nearly 520,000 hectares of catchment area timberland when it hit the Florida panhandle in late-2018. Prior to this event occurring, PPW inventory levels had held relatively steady, decreasing slightly but averaging 47.2 million m3 in the catchment area from 2008-2018. However, the destruction caused by Hurricane Michael resulted in the immediate loss of more than 10.3 million m3 of PPW inventory, or a 22% decrease compared to pre-hurricane levels.

Moreover, the slight decrease in PPW inventory levels that did occur from 2008-2018 was not due to increased demand from bioenergy. Typically, a reduction in inventory is linked to harvest levels above the sustainable yield capacity of the forest area, but in the Cottondale catchment area, annual growth of PPW exceeded annual removals every year throughout this period. Ultimately, the decrease in PPW inventory from 2008-2018 can be more closely linked to decreased pine sawtimber production beginning in the early to mid-2000s. Specifically, annual removals of pine sawtimber decreased 28% from 2003-2014, and the reduction in harvest levels over this period translated to a reduction in newly-re-established pine stands and ultimately the slight reduction in PPW inventory levels that occurred in the mid-to-late 2010s.

Timber growth rates

Neutral. Overall, timber growth rates declined slightly in the catchment area from 2008 (the year Enviva Cottondale commenced operations) through 2020. However, this decrease in timber growth rates was not due to increased demand attributed to bioenergy but rather to the aging of the catchment area forest. Specifically, USFS data shows the average age timber inventory in the Cottondale catchment area increased from an estimated 43.6 years of age in 2008 to 45.7 years of age in 2020.

Forest area

Positive. In the Enviva Cottondale catchment area, total forest area (i.e. timberland) increased more than 55,100 hectares (+1.9%) from 2008 through 2020, and this increase can be linked to several factors, including increases in softwood pulpwood demand (from both bioenergy and other sources) as well as conversion from farmland.

Specifically, the more than 55,100-hectare increase in catchment area timberland from 2008-2020 coincided with a 1.1-million metric ton increase in annual softwood pulpwood demand (roughly half of which was attributed to bioenergy). While statistical analysis identified moderately strong positive relationships between timberland area and both softwood biomass demand and non-bioenergy-related softwood pulpwood demand, a strong positive correlation was found between timberland and total softwood pulpwood demand – suggesting that the increases in timberland since 2008 can be attributed, in part, to the increase in total softwood pulpwood demand (from both bioenergy and other sources).

The more than 55,100-hectare increase timberland from 2008-2020 also coincided with a roughly 75,000-hectare decrease in farmland (i.e. cropland, woodland, and pastureland) over this period. Specifically, the catchment area experienced a roughly 31,800-hectare loss in cropland, 8,900-hectare loss in pastureland, and 34,300-hectare loss in woodland from 2008-2020. Furthermore, statistical analysis confirmed this inverse relationship, identifying a strong negative correlation between timberland and farmland in the Cottondale catchment area.

Wood prices

Negative / Positive. Total softwood pulpwood demand attributed to bioenergy in the Cottondale catchment area increased from zero tons in 2007 (the year prior to Enviva Cottondale’s startup) to over 1.0 million metric tons in 2013. Over this same period, the price of delivered pine pulpwood (PPW) – the predominant roundwood product utilized by Enviva Cottondale for wood pellet production – increased 42% (from $21.06 per ton in 2007 to $29.82 per ton in 2013).

However, the apparent link between increased softwood biomass demand and increased delivered PPW price is only loosely supported by statistical analysis, which identified a relatively weak positive relationship between these two variables. Furthermore, delivered PPW price has remained nearly unchanged in the catchment area since 2013, despite softwood biomass demand declining and averaging roughly 577,000 metric tons per year since 2016. (Note that the roughly 410,000-metric ton decrease in softwood biomass demand from 2013-2020 was offset by a roughly 455,000-metric ton increase in softwood pulpwood demand from other sources). Ultimately, the increase in delivered PPW prices in the catchment area can be linked to increased demand for softwood pulpwood from all sources, and roughly half of the 1.2-million metric ton increase in softwood pulpwood demand since 2007 can be attributed to bioenergy.

However, it’s also important to note that the increase in bioenergy-related wood demand has been a positive for forest landowners in the Enviva Cottondale catchment area. Not only has bioenergy provided an additional outlet for pulpwood in this market, but the increase in delivered PPW price resulting from increased softwood pulpwood demand from bioenergy has transferred through to landowners in the form of higher PPW stumpage prices. Specifically, over the six years prior to Enviva Cottondale’s startup, PPW stumpage price – the price paid to landowners – averaged roughly $7.40 per ton in the Cottondale catchment area. However, since 2010, PPW stumpage prices have averaged more than $11.15 per ton, representing a more than 50% increase compared to pre-mill startup levels.

Markets for solid wood products

Positive. In the Enviva Cottondale catchment area, demand for softwood sawlogs used to produce lumber and other solid wood products increased an estimated 23% from 2008-2020. This increase in softwood lumber production has consequentially resulted in an increase in sawmill residuals (i.e. chips, sawdust, and shavings) – by-products of the sawmilling process and materials utilized by Enviva Cottondale to produce wood pellets.

Specifically, softwood sawlog demand has increased more than 16% in the catchment area since 2014, and this increase in demand has coincided with a nearly 60% increase in pine residual purchases by Enviva Cottondale. (Note that pine residuals constituted 25% of total raw material purchases by Enviva Cottondale in 2014 but 41% of total raw material purchases in 2020). So, not only has Enviva Cottondale benefited from the greater availability of this sawmill by-product, but lumber producers have also benefited, as Enviva Cottondale has provided an additional outlet for these producers and their by-products.

This is part of a series of catchment area analyses around the forest biomass pellet plants supplying Drax Power Station with renewable fuel. Others in the series can be found here.