In brief

-

Policy intervention is needed to enable enough BECCS in power to make a net zero UK economy possible by 2050

-

Early investment in BECCS can insure against the risk and cost of delaying significant abatement efforts into the 2030s and 2040s

-

A two-part business model for BECCS of carbon payment and power CfD offers a clear path to technology neutral and subsidy free GGRs

The UK’s electricity system is based on a market of buying and selling power and other services. For this to work electricity must be affordable to consumers, but the parties providing power must be able to cover the costs of generating electricity, emitting carbon dioxide (CO2) and getting electricity to where it needs to be.

This process has thrived and proved adaptable enough to rapidly decarbonise the electricity system in the space of a decade.

With a 58% reduction in the carbon intensity of power generation, the UK’s electricity has decarbonised twice as fast as that of other major economies. As the UK pushes towards its goal of achieving net zero emissions by 2050, new technologies are needed, and the market must extend to enable innovation.

Bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) is one of the key technologies needed at scale for the UK to reach net zero. Yet there is no market for the negative emissions BECCS can deliver, in contrast to other energy system services.

BECCS has been repeatedly flagged as vital for the UK to reach its climate goals, owing to its ability to deliver negative emissions. The Climate Change Committee has demonstrated that negative emissions – also known as greenhouse gas removals (GGRs) or carbon removals – will be needed at scale to achieve net zero, to offset residual emissions from hard to decarbonise sectors such as aviation and agriculture. But there is no economic mechanism to reward negative emissions in the energy market.

For decarbonisation technologies like BECCS in power to develop to the scale and within the timeframe needed, the Government must implement the necessary policies to incentivise investment, and allow them to thrive as part of the energy and carbon markets.

BECCS is essential to bringing the whole economy to net zero

The primary benefit of BECCS in power is its ability to deliver negative emissions by removing CO2 from the atmosphere through responsibly managed forests, energy crops or agricultural residues, then storing the same amount of CO2 underground, while producing reliable, renewable electricity.

Looking down above units one through five within Drax Power Station

A new report by Frontier Economics for Drax highlights BECCS as a necessary cornerstone of UK decarbonisation and its wider impacts on a net zero economy. Developing a first-of-a-kind BECCS power plant would have ‘positive spillover’ effects that contribute to wider decarbonisation, green growth and the UK’s ability to meet its legally-binding climate commitments by 2050.

Drax has a unique opportunity to fit carbon capture and storage (CCS) equipment to its existing biomass generation units, to turn its North Yorkshire site into what could be the world’s first carbon negative power station.

Plans are underway to build a CO2 pipeline in the Yorkshire and Humber region, which would move carbon captured from at Drax out to a safe, long-term storage site deep below the North Sea. This infrastructure would be shared with other CCS projects in the Zero Carbon Humber partnership, enabling the UK’s most carbon-intensive region to become the world’s first net zero industrial cluster.

Developing BECCS can also have spillover benefits for other emerging industries. Lessons that come from developing and operating the first BECCS power stations, as well as transport and storage infrastructure, will reduce the cost of subsequent BECCS, negative emissions and other CCS projects.

Hydrogen production, for example, is regarded as a key to providing low, zero or carbon negative alternatives to natural gas in power, industry, transport and heating. Learnings from increased bioenergy usage in BECCS can help develop biomass gasification as a means of hydrogen production, as well as applying CCS to other production methods.

The economic value of these positive spillovers from BECCS can be far reaching, but they will not be felt unless BECCS can achieve a robust business model in the immediate future.

With a 58% reduction in the carbon intensity of power generation, the UK’s electricity has decarbonised twice as fast as that of other major economies. As the UK pushes towards its goal of achieving net zero emissions by 2050, new technologies are needed, and the market must extend to enable innovation.

Designing a BECCS business model

The Department for Business Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) outlined several key factors to consider in assessing how to make carbon capture, usage and storage (CCUS) economically viable. These are also valid for BECCS development.

Engineers working within the turbine hall, Drax Power Station

One of the primary needs for a BECCS business model is to instil confidence in investors – by creating a policy framework that encourages investors to back innovative new technologies, reduces risk and inspires new entrants into the space. The cost of developing a BECCS project should also be fairly distributed among contributing parties ensuring that costs to consumers/taxpayers are minimised.

Building from these principles there are three potential business models that can enable BECCS to be developed at the scale and in the timeframe needed to bring the UK to net zero emissions in 2050.

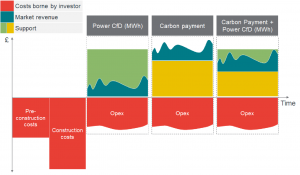

- Power Contract for Difference (CfD):

By protecting consumers from price spikes, and BECCS generators and investors from market volatility or big drops in the wholesale price of power, this approach offers security to invest in new technology. The strike price could also be adjusted to take into account negative emissions delivered and spillover benefits, as well as the cost of power generation. - Carbon payment:

Another approach is contractual fixed carbon payments that would offer a BECCS power station a set payment per tonne of negative emissions which would cover the operational and capital costs of installing carbon capture technology on the power station. This would be a new form of support, and unfamiliar to investors who are already versed in CfDs. The advantage of introducing a policy such as fixed carbon payment is its flexibility, and it could be used to support other methods of GGR or CCS. The same scheme could be adjusted to reward, for example, CO2 captured through CCS in industry or direct air carbon capture and storage (DACCS). It could even be used to remunerate measurable spillover benefits from front-running BECCS projects. - Carbon payment + power CfD:

This option combines the two above. The Frontier report says it would be the most effective business model for supporting a BECCS in power project. Carbon payments would act as an incentive for negative emissions and spillovers, while CfDs would then cover the costs of power generation.

Cost and revenue profiles of alternative support options based on assuming a constant level of output over time.

Way to go, hybrid!

Why does the hybrid business model of power CfD with carbon payment come out on top? Frontier considered how easy or difficult it would be to transition each of the options to a technology neutral business model for future projects, and then to a subsidy free business model.

By looking ahead to tech neutrality, the business model would not unduly favour negative emissions technologies – such as BECCS at Drax – that are available to deploy at scale in the 2020s, over those that might come online later.

Plus, the whole point of subsidies is to help to get essential, fledgling technologies and business models off to a flying start until the point they can stand on their own two feet.

The report concluded:

- Ease of transition to technology neutrality: all three options are unlikely to have any technology neutral elements in the short-term, although they could transition to a mid-term regime which could be technology neutral; and

- Ease of transition to subsidy free: while all of the options can transition to a subsidy free system, the power CfD does not create any policy learnings around treatment of negative emissions that contribute to this transition. The other two options do create learnings around a carbon payment for negative emissions that can eventually be broadened to other GGRs and then captured within an efficient CO2 market.

‘Overall, we conclude that the two-part business model performs best on this criterion. The other two options perform less well, with the power CfD performing worst as it does not deliver learnings around remunerating negative emissions.’

Assessment of business model options. Green indicates that the criteria is largely met, yellow indicates that it is partially met, and red indicates that it is not met.

Transition to a net zero future

Engineer inspects carbon capture pilot plant at Drax Power Station

Crucial to the implementation of BECCS is the feasibility of these business models, in terms of their practicality in being understood by investors, how quickly they can be put into action and how they will evolve or be replaced in the long-term as technologies mature and costs go down. This can be improved by using models that are comparable with existing policies.

These business models can only deliver BECCS in power (as well as other negative emissions technologies) at scale and enable the UK to reach its 2050 net zero target, if they are implemented now.

Every year of stalling delays the impact positive spillovers and negative emissions can have on global CO2 levels. The UK Government must provide the private sector with the confidence to deliver BECCS and other net zero technologies in the time frame needed.

Go deeper

Explore the Frontier Economics report for Drax, ‘Supporting the deployment of Bioenergy Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS) in the UK: business model options.’